Articles and Features

Museums Without Walls: How Artists’ Books Have Created a New Genre

By Adam Hencz

“An art book is a museum without walls.”

André Malraux

What happens when artists approach the format or concept of the book, not simply to document or illustrate their work but as an art practice in its own right?

Allowing the artist to cross boundaries and defy existing limitations and definitions, books have become a medium of expression that not only enables but also calls for the combination of several modes of creation, ultimately creating an entirely new genre.

Artists’ books, in this sense, can take many forms, from luxury letterpress volumes with original prints to duplicated pamphlets, 3D constructions and altered existing books. We explore the medium from its origins to recent times.

Artists have been associated with the written word since illuminated manuscripts were developed in the medieval period. However, it is rare to see instances of artists and writers experimenting with the conventional structure of the book before the 20th century. One early outlier can be seen in the work of Laurence Sterne. In his novel The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759–67), a colourful marbled paper, of the kind usually seen at the front or back of a book, suddenly interrupts the narrative, challenging the reader’s assumptions about the book’s structure.

Many have been concerned with books as an artistic enterprise, notably William Blake at the end of the 18th century and William Morris at the Kelmscott Press from the 1890s, but it was not until the early 20th century that Avant-garde artists began to produce many books as part of their artistic endeavours. The first half of the century saw in fact experiments with visual text and layout by Apollinaire, Marinetti and Picabia, among others, but also Max Ernst’s collage graphic novels. In the 1950s, recognised artists’ books appeared by Guy Debord and Asger Jorn, and Dieter Roth’s lifelong series began. But it was in the 1960s that persistent and wide-spread questioning of the book’s conventions really accelerated and, out of this activity, artists’ books surfaced as a genre.

In the 1960s, conceptual art emerged as a bold new movement. Its advocates believed in art as an idea, or concept, able to exist in the absence of an object as its representation. Many conceptual artists critiqued and wanted to dismantle established structures of the art establishment. Some felt a need to move away from the conventional ‘spaces’ of art, such as the studio and the gallery, which they saw as elitist, looking instead for new ways to present their ideas and some artists viewed books as a satisfying solution.

Artists also viewed books as a democratising medium since they could publish their books in editions or even as mass-produced publications, making them potentially cheap to manufacture and inexpensive to buy. Through the book, artists could communicate complex ideas to a wide audience by means of an accessible medium.

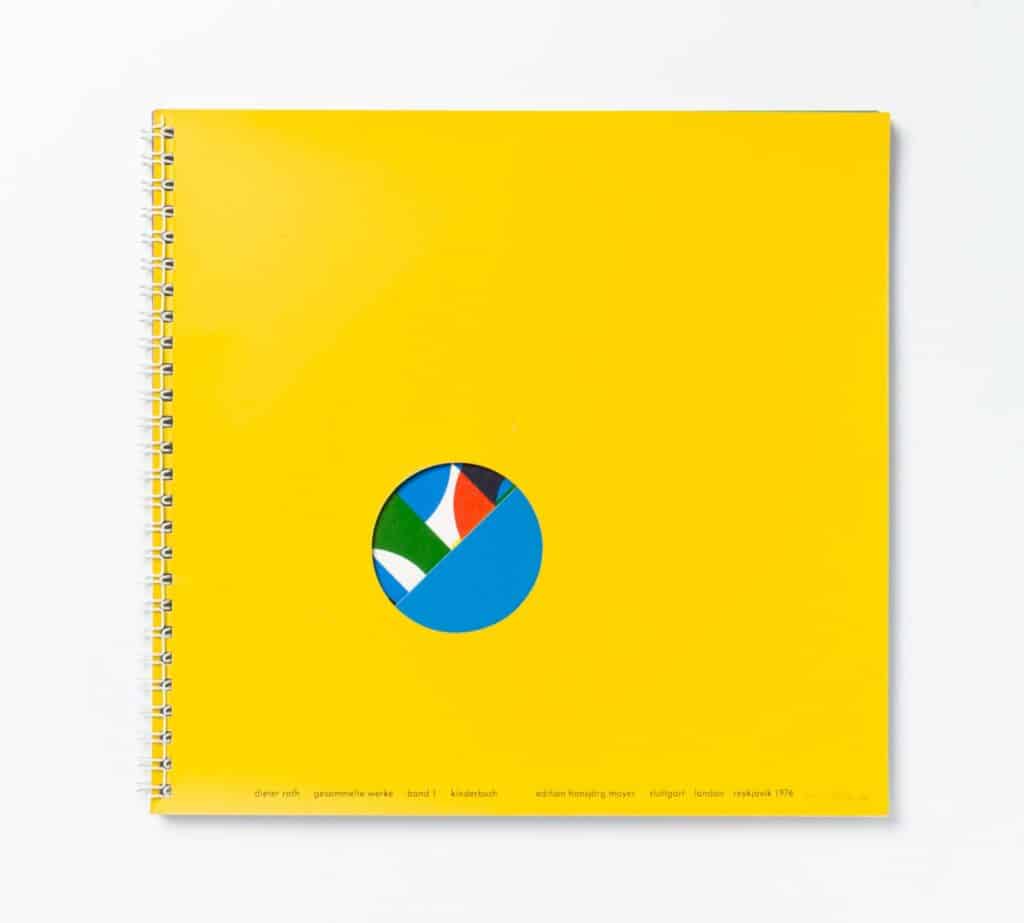

The origins of artists’ books: Dieter Roth’s radical experiments

The origins of artists’ books are complex and fragmented but conceptual works created in the 1950s and 1960s by Swiss-German artist Dieter Roth (1930–98) are considered the foundation of the artist’s book genre. Roth’s distinctive contribution to the genre was his examination of the formal qualities of books themselves, first and foremost the binding of flat pages bound into a fixed sequence. These qualities were deconstructed and investigated to the point that the investigation became the subject matter of the book itself. For example, 2 Bilderbücher (1957) consists of two picture books of geometric shapes with die-cut holes cut into each page to allow glimpses of patterns from the pages beneath. Subsequent works such as Daily Mirror (1961) involved the use of found materials manipulated to a particular purpose, a technique that was much used by later book artists.

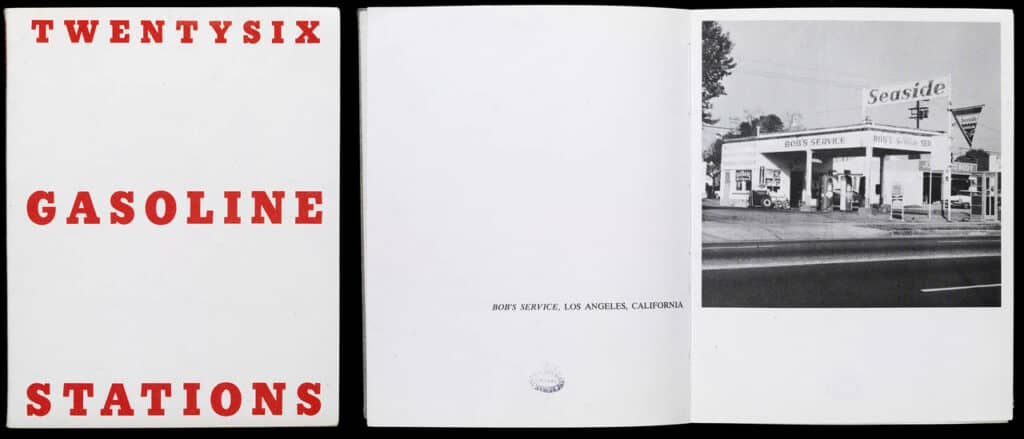

Twentysix gasoline stations by Ed Ruscha

Ed Ruscha‘s Twentysix gasoline stations (1963) is also often credited as a convenient starting point for the artists’ book genre. The piece is a modest-looking publication containing 26 photos of petrol filling stations on the route between Ruscha’s home in Los Angeles and his parents’ place in Oklahoma. The black and white photos are resolutely plain and literal while the text below them indicates nothing but the name of the gasoline station and its location on the highway. Even the book’s title is deliberately enigmatic, printed across an otherwise plain white cover in bold red text. Ruscha described LA as “the ultimate cardboard cut-out town” and the form of the book, with its sequential pages, was the ideal medium for expressing this impression of repetitive flatness. The book is therefore not just a container for reproductions of Ruscha’s photographs, its very form embodies his concept, also communicating it to the reader.

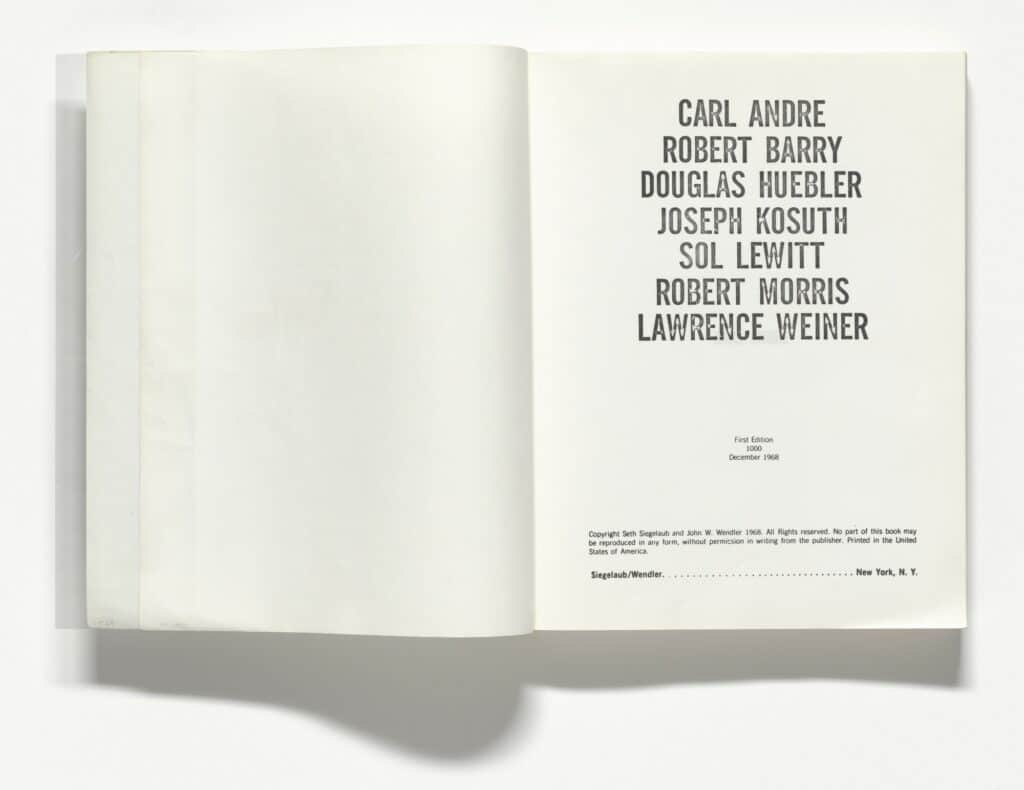

The Xerox Book

Access to new technologies of multiplying images and texts, from photography to high street printing to computers, has been highly important to the development of artists’ books. Andre Barry Huebler Kosuth LeWitt Morris Weiner is commonly referred to as The Xerox Book owing to its original conception as a book to be produced using the Xerox photocopiers. The publication was ultimately printed using commercial offset lithography when the costs of using photocopiers proved to be higher than traditional printing.

he Xerox Book comprises original projects made for the pages of the publication by the seven artists named in its title. The pioneering art dealer Seth Siegelaub offered each artist twenty-five pages in which to create a work that could only be seen as a serialized, page-by-page progression formatted for a book. Both the artists and the publishers viewed the pages of The Xerox Book as a singular exhibition venue for new artistic presentations, one that contains art in the same way a museum or commercial art gallery does.

The Xerox Book, 1968 © 2021 Carl Andre

Expansion of artists’ books

Artists’ books became popular throughout the 1960s and early 1970s and the genre has continued to expand. During the 1980s and 1990s, many more artists began to use the book as a medium for self-expression and still continue to do so. Techniques remain varied and range from the traditional to the experimental. Small presses and individuals have continued to promote the art of letterpress printing and producing hand-crafted books. Some artists have chosen to use computer-generated images while others have used the photocopier to reproduce their work.

Many have taken up the challenge to experiment with the content and physical structure of the traditional book form and artists’ books have continued to step outside conventional boundaries to encompass concepts associated with the fine arts.

A personal connection

Artists’ books can take many forms and are not restricted to the use of paper and ink but can incorporate all kinds of materials and appended objects instead. While such works are usually unique or limited editions, some are produced in multiple copies.

Despite the genre’s wide variety, a few common elements can be identified across the practice. In particular, conceiving a book as an artwork invites a reflection on the properties of the book form itself. Much like any act of reading, an artist’s book is a physical experience that allows a connection with the medium that is individual and personal, inviting us to hold it and turn through its pages. Whether the content is visually or linguistically based, or a mix of both, the act physically moving through it implicates notions of sequence, repetition, juxtaposition, and duration. Ultimately, the interplay of text and images, as well as considerations of the printing process and the design of the book, allows for many exciting possibilities within narrative, media, and meaning that are specific to the artists’ book alone.

Relevant sources to learn more

Artists’ book on MoMa

Dieter Roth’s artists’ books at the MCA Collection