Articles and Features

Commercial Art? When Fine Art Is Enlisted To Sell

By Pablo Anton

The relationship between art and advertising has always been complex. Many of today’s societies fundamentally rely on the consumer power of their populations, continuously seeking to sell more units through as many channels as possible, and utilising whatever means necessary. Historically, the role of art in society has been set aside from such naked commercialism – occupying a higher realm alongside literature and music, and traditionally tasked with providing culture, beauty, erudition, satire and critique amongst other high-minded goals. But has it been as sequestered from the peddling of merchandise as it likes to think?

The Early Case of Bubbles for Pears Soaps

The painting Bubbles by Sir John Everett Millais is probably one of the earliest examples of commercial art, where a reputed, albeit saccharine art work by a renowned master was overtly used for selling purposes. This late 19th-century painting by one of the founders of the Pre-Rapahelite brotherhood was used by the British soap company Pears and was the first artwork modified to serve the needs of print advertising.

The painting which was based on 17th-century Dutch genre painting precursors, depicted the artist’s own grandson Willam Milbourne James innocently playing with bubbles. The piece was sold to A & F Pears’ manager Thomas J. Barratt for £2,200, the high price of which crucially gave full copyright ownership of the artwork to the company, and which was subsequently commercially exploited for generations.

The Proliferation of Commercial Art

Arguably, a key turning point in the merger between art and its mercantile exploitation took place during the Art Nouveau movement of the late 19th-century. This artistic movement, which was first popularized by French gallery Maison de l’Art Nouveau (“House of the New Art”) in Paris, was a revolutionary style of natural forms and sinuous movement, set against the staid traditionalism of prevailing academic art.

Alphonse Mucha, one of the key figures and whose work is often considered the apogee of Art Nouveau, was a Czech painter born in 1860. His art is an essential milestone when explaining the transition art can make–from fine to commercial art–in the service of consumerism. Mucha’s technique and style perfectly matched the concept that art could be consumed as advertising – crisp, graphic and eminently reproducible, with a knack for including chic models. Basing his work on female models, the artist gained great fame for his portraits of famous French 20th-century actress Sarah Bernhardt, which in turn were used for commercial posters. The use of celebrities in brand endorsement is of course commonplace and has been for the last century–the work of Mucha has a legitimate claim to be the first of this kind.

The poster shown above is a wonderful example of how Mucha’s art effortlessly promotes lifestyle improvement attributable to the product. Here, something as mundane as a biscuit becomes a glamorous and luxurious thing, raising irresistible desires in the mind of the spectator.

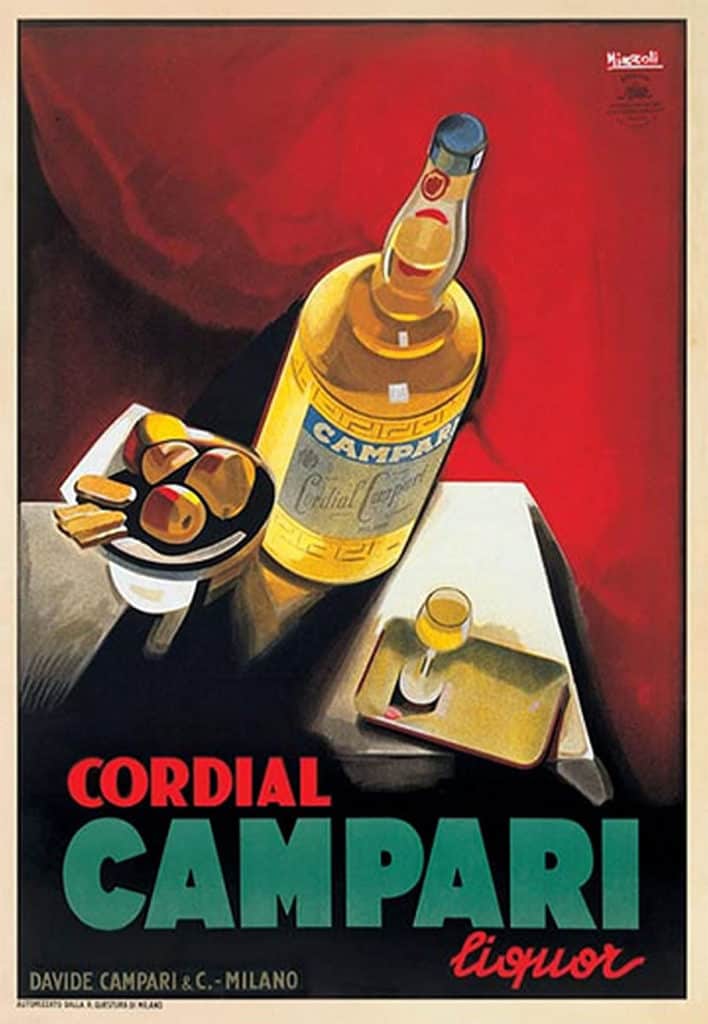

Inspired by the Banality of Commerce

There are always two different sides to a story, and we see that art also exploits the concepts of mass production and consumption for its own benefit. This is the case with Juan Gris’ artwork La Botella de Anis (“The Annis Bottle”), when the noted early proponent of Cubism decided to produce art based on a popularly consumed product in Spanish Culture.

The consumption of this liquor in Spain is immense, especially around Christmas time. The drink is so popular that there are many different idiomatic cultural references honoring the beverage. The dominant brand in the country is “Anis del mono”, whose bottle and label was specifically picked by Gris as an attempt to bring a popularly consumed yet banal product to the cutting edge spotlight afforded by this new type of painting. From its characteristic label to the resounding name of the brand, Gris was able to relate a common and popular brand to the esoteric forms of cubist painting, making a hitherto esoteric painting style relatable to many.

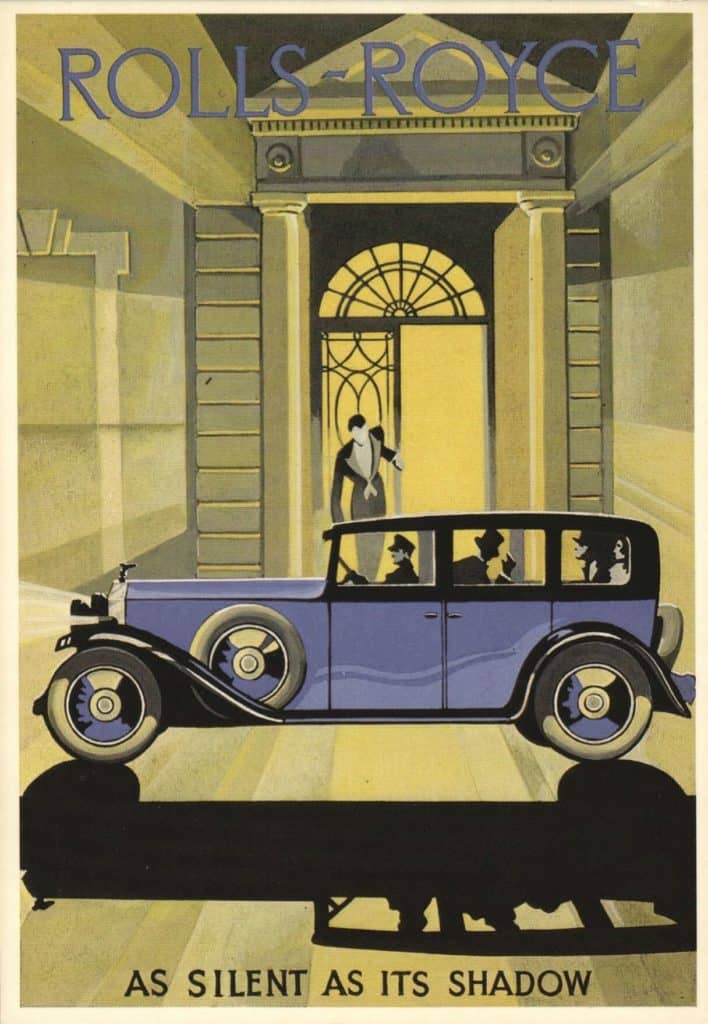

Art + Deco. a New Era in Advertising

During The Roaring Twenties, the C20th century’s first era of excess which spanned the 1920s and early Thirties, we find major developments in the influence art exerted over advertising. This decade was the decade of Art Deco, an art movement that aimed to express glamour, exuberance, and technological and social progress, many of the different characteristics that can be attributed to a capitalist society whose main objective is production and the selling of these wares.

Art Deco’s spirit is fully represented by the famous Chrysler Building in New York City, an endless steel construction that reminds society of the perks of staying productive. This art movement fully embraced the art of advertising and greatly influenced all visual culture, including the graphic design of billboards created for commercial purposes. The posters had a characteristic layout and typography, which aimed to communicate the glamour and power of cosmopolitan societies.

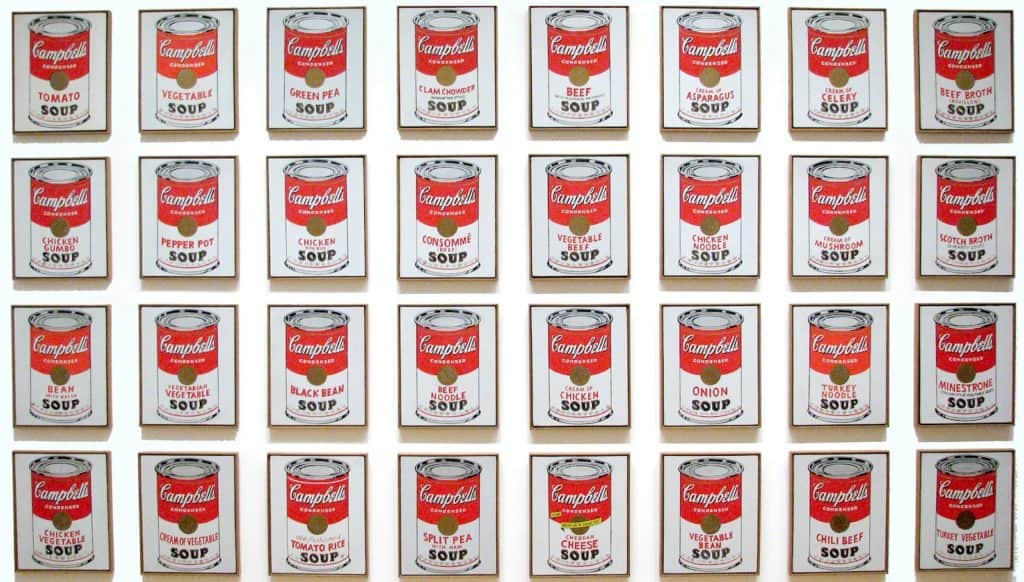

The Mass Consumption Art Movement

In the 1950’s we clearly saw for the first time how the power roles occupied by art and advertising were reversed, and how art came to be the pre-eminent force exploiting notions of consumption. At the end of the decade, and during the beginning of the 1960s, Pop Art emerged as a revolutionary movement based on the imagery of popular culture as represented by mass media, advertising, and mass-produced cultural objects. Pop Art ironically based its focus on the mundane and banal aspects of a consumption-driven society.

One of the most iconic artworks associated with Pop Art is Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s Soup Cans, a piece produced in 1962 featuring 32 illustrations of Campbell’s soup cans, with one iteration for each of the wide range of available flavours.. Following Juan Gris’ precedent, Warhol identified a popularly consumed grocery staple, depicted it as an art that could be consumed by everyone. Art, advertising and the homogeneity of popular mass culture were becoming interchangeable.

Logos, an Evolution In The Relationship

Even if economic power always finds a way to control the production and deployment of art in advertising, art has also had its say in the formation of commercial identities and branding. Companies have always strived to be distinctive, recognized and memorable in a competitive economy, firstly to guarantee survival, and then to exert market dominance. For this reason, companies came up with the idea of logos, a whole category of artistic iconography designed to represent the identity and core of an enterprise.

1969 saw the Spanish brand of lollipops, Chupa Chups, hire surrealist painter and provocateur Salvador Dalí to design its commercial logo. The logo consisted of a yellow daisy-shaped figure with the brand’s name in the middle. In the artistic design of something as fundamental as a brand logo, we see how the relationship between art and consumption evolved in a more interconnected way, establishing a co-dependency more enduring than the ephemerality of a single marketing campaign.

Critiquing the System

Overall, the relationship between commercial art and advertising has often proven to be beneficial for both sides. But this relationship has always been complex and conditional, as art has retained its tendency and prerogative to both represent and criticize the prevailing reality of the times. So, if art can be a source of nourishment for advertising, it can equally represent its fiercest critic and foe. There are many artists who have used their voice and influence through their art to denounce the many flaws that can be found in a capitalist society.

Bansky, the acclaimed street artist from London, made a highly pointed example of advertising and mass consumptions’ omnipotence in a famed graffiti of 2004. The art piece represented the anxiety of a society drowning under deluges of meaningless advertising. A screaming little girl (derived from a famous photograph taken in the aftermath of the bombing of a Vietnamese village in 1972) is seen holding hands with Ronald McDonald and Mickey Mouse, two exemplars of the pervasive toxicity of branding, and indicative of society’s lost sense of priorty..

Art as Advertising’s Detox

There are artists who have more subtle ways of criticizing the effects of consumerism in society. In an attempt to see a city free of advertising, Parisian artist Ettiene Lavie created a project titled “OMG! who stole my ads?” in 2014. The campaign replaced all promotional material from advertising billboards in Paris with classical pieces of art.

The artist’s project pursued the idea of relieving society of the overwhelming pressure to consume, replacing it instead with the profundity of great art. Even if the project was entirely digital, the many images of Parisians surrounded by great works of Delacroix or Ingres in their daily lives gave a sense of calm and sophistication often missing amidst the chaos and hectic intensity of contemporary urban life.

Relevant sources to learn more:

Read more about Art Deco advertisements here

Learn more about Andy Warhol’s ‘Campbell’s Soup Cans’