Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts – Leonora Carrington

By Tori Campbell

“I didn’t have time to be anyone’s muse…I was too busy rebelling against my family and learning to be an artist.”

Leonora Carrington

In this article series, we discuss some of the most boundary-breaking female iconoclasts of our time; women who defied social conventions in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to society. Last edition featured the work of art deco icon and symbol of women’s liberation, Tamara de Lempicka. This week we focus on the exceptional work of surrealist painter and writer Leonora Carrington.

Early Life

Born April 6th, 1917 in Clayton Green, Lancashire to a wealthy family, Leonora Carrington grew up in a manor home (Crookhey Hall) under the care of an Irish nanny full of folk tales. After being expelled from two different Roman Catholic convent schools for her vivacious and rebellious behavior, she was sent to Florence to attend Mrs. Penrose’s Academy of Art. Upon her return, and despite her father’s resistance to an artistic career, she enrolled in an art school recently founded by French modernist Amédée Ozenfant. Her mother meanwhile, quietly supported her career by giving her what would become the most influential gift of her life, a copy of Herbert Read’s new book Surrealism (1936).

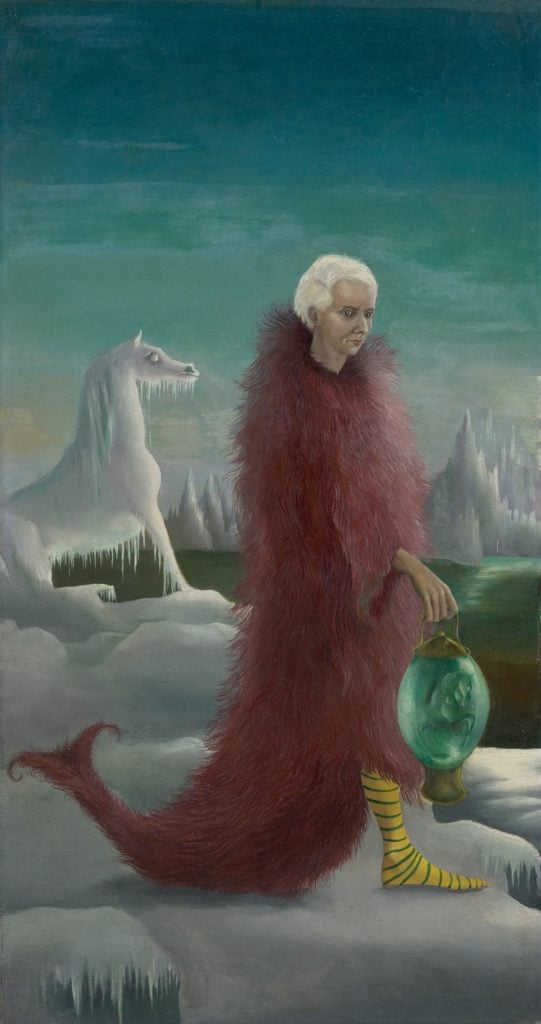

Courtesy of the National Galleries of Scotland, copyright the estate of Leonora Carrington, DACS, 2018.

Relationship with Max Ernst

Later that year Carrington attended the International Surrealist Exhibition in London and was impressed by her first encounter with German surrealist artist Max Ernst’s work. Shortly thereafter they met and quickly forged such a strong bond that by 1938 Ernst had left his wife and together he and Carrington had settled into the town of Saint Martin d’Ardèche in southern France. The two supported one another’s artistic development, and created numerous works to decorate their new home together. She and Ernst became familiar with other Surrealists such as Salvador Dalí, Marcel Duchamp, Joan Miró and Man Ray; though she was unmoved by their fascination with Freud and she continued to illustrate female sexuality as experienced by women, a rare perspective at this time.

“I’m like a hyena, I get into the garbage cans. I have an insatiable curiosity.”

Leonora Carrington, 1999

The Inn of the Dawn Horse

During this time, from 1937-1938, Carrington painted one of her most famous pieces, Self-portrait also called The Inn of the Dawn Horse. The piece depicts the corner of a room with a lushly curtained window, through which we see a landscape with a horse in the distance. Leonora is in the center of the painting, clad in white jodhpurs, a hand extended towards a lactating hyena. Above and behind her wild crown of hair hovers a white tailless rocking horse — her eyes are sternly focused directly at the painting’s viewer. The piece is the first of Carrington’s Surrealist works packed full of symbolism. The appearance of a horse in Carrington’s work would prove to be a theme in her oeuvre, representing freedom and independence. Her interest in Celtic mythology, from her childhood nanny, would mean that Carrington was familiar with the Celtic goddess Epona, goddess of fertility, who rode a white horse. As for the hyena, Carrington was known for identifying not only with horses, but also with the raw and wild animalism of the hyena.

A Split with Max Ernst

In 1939 Carrington painted Portrait of Max Ernst in contemplation and reflection of the lack of clarity in their relationship. With the outbreak of World War II, Ernst was arrested multiple times due to his engagement with what the Nazi regime declared “degenerate art”, and ultimately fled to the United States with Peggy Guggenheim, a famous patron of the arts, whom he would go on to marry. After Ernst’s departure, she fled to Spain where she experienced numerous mental health issues. After a breakdown at the British Embassy in Madrid; her parents had her hospitalised where she received devastatingly poor care, was heavily drugged, and lived in abusive conditions. She would later go on to write about her experience and hospitalisation after urged by friend André Breton in the novel Down Below, where she illustrates unsanitary conditions, sexual assaults, and hallucinatory drugs.

An Adopted Home

When temporarily out of the hospital with a nurse in Lisbon; Carrington fled to the Mexican Embassy where she met Mexican Ambassador, and friend of Pablo Picasso, Renato Leduc. Leduc married Carrington to provide her with the immunity and protection given to diplomat’s wives, and together they moved to Mexico. Though she fell in love with the country, she never fell in love with Leduc, and they divorced in 1943.

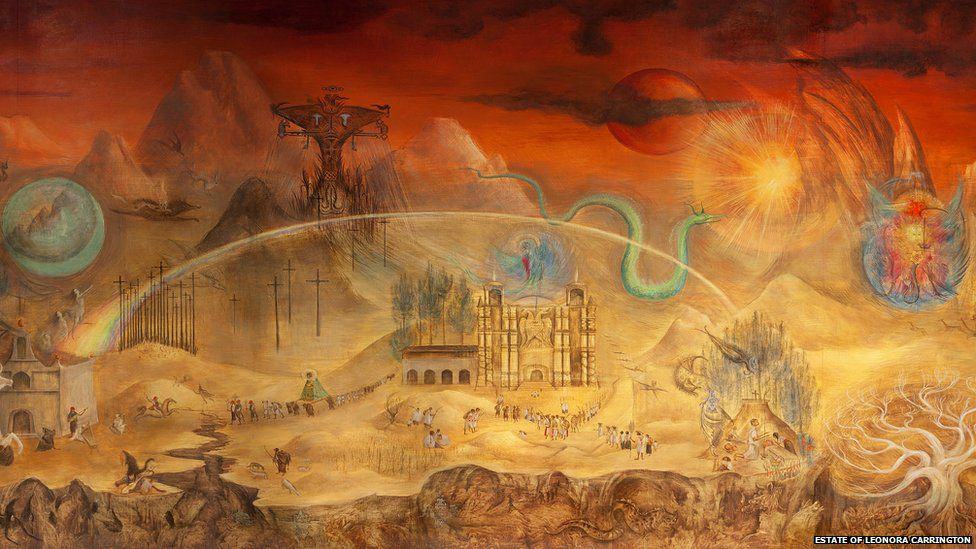

© 2019 Estate of Leonora Carrington /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

© 2019 Estate of Leonora Carrington /

Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Fascinated by Mexican history, traditions, and folklore; she was absorbed by her new culture and ultimately became regarded as a Mexican artist. Carrington spent time as a member of a group of Mexican artists commissioned to create works reflective of the country’s culture, where created El Mundo Mágico de los Mayas (1963), a renowned mural informed by regional folklore, for Museo Nacional de Antropología in Mexico City. Her work developed and blossomed while in Mexico, and she spent more and more time experimenting with themes of female sexuality, alchemy and magic, and emancipation. As an adopted national treasure, Carrington grew even more invested in Mexico, and in 1973 she created Mujeres Conciencia, a poster for the Women’s Liberation movement. Her political commitment and importance to the movement led to her winning the Lifetime Achievement Award at the Women’s Caucus for Art in 1986.

Courtesy of the Estate of Leonora Carrington

Death and Legacy

Leonora Carrington died at the age of 94, on 25 May 2011, in Mexico City. However, her rich legacy as an integral figure in the Surrealist movement (and one of the only women), reputation for her reverent depictions of Mexican folklore, and engagement with the Women’s Liberation movement; means that she will live on for centuries to come. Her work can be found in the collections of The Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, and the Tate Gallery in London, among countless other notable institutions.

Relevant sources to learn more

Enjoy an article about befriending Leonora Carrington here

Check out the Google Doodle created for her 98th birthday