Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: Mona Hatoum

By Shira Wolfe

“Although I was born in Lebanon, my family is Palestinian. And like the majority of Palestinians who became exiles in Lebanon after 1948, they were never able to obtain Lebanese identity cards. It was one way of discouraging them from integrating into the Lebanese situation. […] When I went to London in 1975 for what was meant to be a brief visit, I got stranded there because the war broke out in Lebanon, and that created another kind of dislocation, [which] manifests itself in my work…” – Mona Hatoum in BOMB Magazine

In our “Female Iconoclasts” series, we discuss some of the most boundary-breaking female iconoclasts of our time; women who defied social conventions in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to society.

This week, we feature Mona Hatoum, the London-based Palestinian artist who became widely known in the 1980s for her series of performance pieces and video works focusing on the body. Hatoum’s often surrealist poetic and political oeuvre covers a diverse range of media, from installation, sculpture and video art to photography and works on paper.

Mona Hatoum, a Palestinian in Beirut

Mona Hatoum was born in Beirut, Lebanon in 1952. The daughter of Palestinians who were exiled after the State of Israel was created in 1948, her family, like many other Palestinian exiles in Lebanon, were never able to obtain Lebanese identity cards. Hatoum grew up with the deeply complex identity of being a Palestinian who had never lived in Palestine, a country which now was no longer officially recognised by the world, living in Lebanon, a country which did not officially recognise her family as citizens.

Mona Hatoum, London

In 1975, Hatoum went on a short trip to London, where she got stranded due to the outbreak of the Lebanese Civil War. In her words, “that created a kind of dislocation, [which] manifests itself in my work…” She continues to live and work in London to this day. Hatoum studied art at the Slade School of Fine Art, and continued developing ideas surrounding gender and race. She also started to explore the relationship between politics and the individual through performance.

“Often the work is about conflict and contradiction – and that conflict or contradiction can be within the actual object.” – Mona Hatoum in TateShots

The Works of Mona Hatoum in the 1980s

In the mid 1980s, Hatoum first rose to fame with her series of performance and video works focusing intensely on the body, interlacing her personal experiences into her artistic practice.

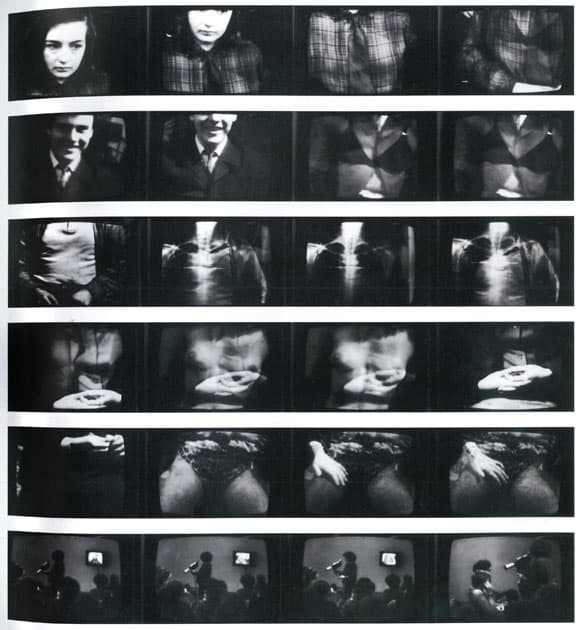

One of Hatoum’s first performances, in 1980, was “Don’t Smile, You’re on Camera.” The work involved Hatoum panning the camera across the audience, while showing the live images on a monitor. She stopped to focus on the body part of a member of the audience, and then another, while on screen the clothes would fade away to reveal naked body parts or an X-ray image. This work explored ideas of surveillance that would recur in later works, such as the prying eye of the state invading one’s personal boundaries.

Her 1982 work “Under Siege” caused a controversy, as Hatoum, naked and covered in liquid clay, struggled to stand up in a transparent plastic structure. The clay, sticking to her body, made Hatoum almost invisible, as she continued to fall and stand up again, leaving traces of clay on the plastic with her body. The performance directly refers to a state of siege. Revolutionary songs in Arabic, French and English, as well as news reports and statements about the situation in the Middle East were played. This work was Hatoum’s first attempt at making a statement about the persistent struggle to survive in a country which in essence is under a continuous state of siege. The action was a type of reconnection and reconciliation with her own background and the history of her people.

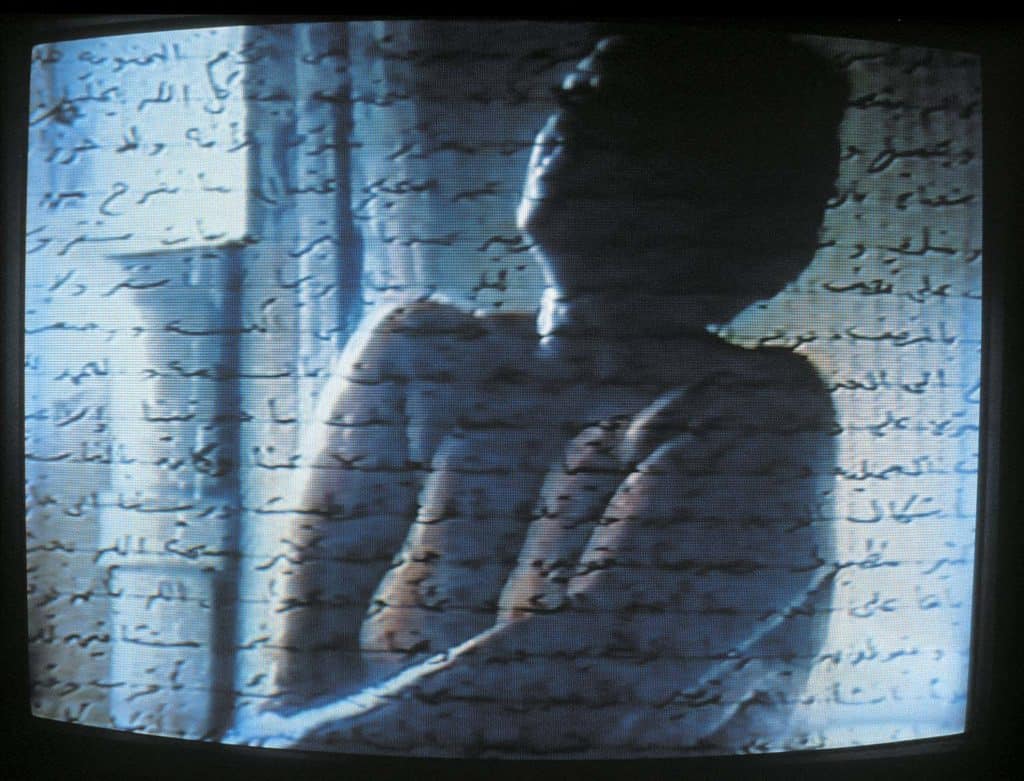

In 1888, Hatoum made “Measures of Distance,” one of her most famous video works constructed from images of her mother showering in their family home in Beirut. Writing in Arabic, taken from her mother’s letters to Hatoum in London, overlay the images like a sheer veil. The soundtrack consists of a conversation between Hatoum and her mother, and Hatoum’s voice reading a translation of the letters into English. The work both portrays the emotional intimacy between mother and daughter, and also speaks of exile, displacement and loss due to separation caused by war.

Developments in the 1990s

In the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, Hatoum’s work focus moved towards large-scale installations and sculptures that aimed to engage the viewer in a variety of conflicting emotions, such as desire and revulsion, fear and fascination. She often used the grid or geometric forms to reference to systems of control in society, and created works using household objects which she either enlarged or altered in order to make the familiar uncanny.

Her 1994 video installation “Corps étranger”, first exhibited at Centre Pompidou, confronted the audience with images from an internal endoscopic examination of Hatoum’s own body projected onto the floor of a cylindrical structure, while her heartbeat marked time. She also made works on handmade paper with her nail cuttings, hair and bodily fluids embedded in the paper pulp. Her idea was to work with bodily discards and abject material, and the work was filled with symbols and suggestions.

Mona Hatoum’s Visual Language

Making the familiar uncanny became Hatoum’s signature artistic language, and has earned her the title of a “latter-day surrealist.” She transforms familiar, everyday objects into foreign, threatening, even dangerous things. Her piece “Jardin public” (1993) comprises a metal garden chair, adorned by a clump of pubic hair. The work comments on the fact that women are often treated like public gardens, free to be watched and used at all times. It is also reminiscent of René Magritte’s “Le Viol (The Rape)” (1934), in which a woman’s eyes have been replaced by breasts, and her mouth by a vagina.

An example of Hatoum’s transformation of everyday, domestic objects into alien things is “Homebound” (2000), an assemblage of household furniture wired up with an audibly active electric current that combines a sense of threat with a surrealist sense of humour.

Hatoum also often makes use of cartography in her work. In “Hot Spot” (2006) and “Map (clear)” (2015), she employs cartography to explore the sense of instability and precariousness in our contemporary political landscape. The title “Hot Spot” refers to a place of military or civil unrest. This sculpture, outlined with red neon to delineate the contours of the continents, presents the entire globe as a danger zone.

Exhibitions, Awards and Visibility

Mona Hatoum has participated in many important group exhibitions including the Turner Prize (1995), Venice Biennale (1995 and 2005), Documenta, Kassel (2002 and 2017), Biennale of Sydney (2006), Istanbul Biennial (1995 and 2011) and Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art (2013).

A major touring exhibition with over a hundred works from the late 1970s to the present was on display at the Centre Pompidou, Paris (2015), Tate Modern, London and KIASMA, Helsinki (2016). Recent solo exhibitions include The Menil Collection, Houston, Texas (2017) which toured to the Pulitzer Arts Foundation, St Louis, Missouri (2018).

Hatoum won the 2011 Joan Miró Prize, and was awarded the 10th Hiroshima Art Prize in 2017. In 2019, Hatoum was the recipient of the Praemium Imperiale in recognition of her lifetime achievement in sculpture. She will be the recipient of the 2020 Julio González Prize, Institut Valencià d’Art Modern (IVAM), and a solo exhibition of her work will be held there this year.