Exhibitions and Fairs

The Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection: Five Stellar Pieces

By Shira Wolfe

“The works on show create an arch bridging more than 250 years of art history, […] moving through key figures of Symbolism, such as Odilon Redon, Max Klinger, and Alfred Kubin, and culminating in the main protagonists of the Surrealist movement, including Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, and René Magritte.” – Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection

Located across from Museum Berggruen, in the eastern Stülerbau opposite Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin, is the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection. The art on view here belongs to the Dieter Scharf Collection in memory of Otto Gerstenberg (1848–1935). Otto Gerstenberg, the CEO of the Victoria-Versicherung Berlin insurance company, was an avid art collector, who built one of the most important private art collections in Germany in his lifetime.

The initial focus of Gerstenberg’s collecting was on the old masters, in particular works in the graphic medium by Albrecht Dürer, Francisco de Goya, and Rembrandt. Later, he became interested in French Impressionism and art from the period around 1900. He collected paintings by Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. However, most of his collection was destroyed in the Second World War, and what was left of it was handed down to his grandsons Walther and Dieter Scharf in 1961. They then integrated the works into their own collections.

Dieter Scharf inherited prints by Francisco de Goya, Charles Meryon, and a lithograph series by Édouard Manet. He used these as a starting point for his collection, which came to focus predominantly on Surrealist art. The collection contains over 300 works by more than 50 artists, and covers more than 250 years of art history, beginning with works by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, Francisco de Goya, and Victor Hugo, and continuing with key figures of Symbolism including Odilon Redon, Max Klinger, and Alfred Kubin, culminating in the key artists of Surrealism, such as Salvador Dalí, Max Ernst, André Masson, and René Magritte. Jean Dubuffet continues the Surrealist tradition in the postwar period.

Last week, we featured five artworks at Museum Berggruen, across the road from the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection. This week, we explore five key pieces from the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection.

1. Odilon Redon, Holy Woman in a Boat, c. 1897

Odilon Redon (1840-1916) was a French Symbolist artist, whose dreamlike, mysterious style captured a variety of motifs including mythological scenes and dreams. He was a master at blending naturalism with symbolic subject matter, creating highly representational works based on the principle of the essential need for descriptive accuracy while depicting scenes deriving from the supernatural.

“Holy Woman in a Boat” is a captivating painting, showing a solitary woman on her knees, praying in a sailboat that appears to be braving the rough waves of the sea. Offset against a rich blue sky dotted with silver, the scene is at once a deeply evocative journey into inner psychological states and a glimpse into otherworldly, spiritual matters.

2. René Magritte, Gaspard de la Nuit, 1965

René Magritte was a Belgian Surrealist artist, known for his uncanny scenes focused on making the familiar strange, and posing questions about the nature of representation and reality. Magritte pursued a figurative style that challenged the real world, through a naturalistic and detailed depiction of ordinary subjects and objects.

Magritte’s “Gaspard de la Nuit” was based on the eponymous poem by French poet Aloysius Bertrand. The poem was also the source of inspiration for Ravel’s musical masterpiece by the same name. The scene is filled with contradictory images: we see a burning house in a sparse landscape, beneath the sliver of a moon emerging from parting clouds. A black raven oversees the scene from behind a red curtain on the right side of the canvas.

3. Max Ernst, Barbarians Marching to the West, 1937

Max Ernst was one of the core members of DADA in 1919 and 1920, and became one of the founding members of the Surrealist movement in Paris in 1924. He was fascinated with Freud’s theory of private mythologies and childhood memories. One of the themes he often worked with in his Surrealist phase was the bird, which he frequently depicted incorporating human elements.

Ernst’s painting “Barbarians Marching to the West” portrays the transformation of democracy into barbarism. The painting belongs to a series Ernst started in 1935 titled “The Barbarians.” The bird-like creatures in this series embody the expression of Ernst’s fearful anticipation of World War II, and the impending horrors in Europe. This painting depicts two dark, bird-like figures marching westwards. One leads the other forward by indicating the way. The skeleton of another bird creature hovers ominously above the bird on the left, as though foreshadowing the death and destruction to come.

4. André Masson, Massacre, 1933

After a short period of time during which he was associated with the Cubists in Paris, André Masson (1896-1987) became acquainted with the Surrealists during the 1920s. They introduced him to the concept of automatic writing, whereby they would allow for words to stream out from their subconscious automatically, without consciously writing. In 1924, André Breton invited Masson to join the Surrealist group and he began publishing his automatic drawings in 1925 in the journal La revolution surrealiste (The surrealist revolution). By 1929, he began to distance himself from the Surrealists, believing them to be too dogmatic. He made his final break with them in 1943.

It was in this transitional period, when Masson had already distanced himself from the Surrealists but still maintained contact with them, that he produced the arresting pen-and-ink drawing “Massacre” from 1933. In this period, between 1931-1933, Masson produced an entire series named “Massacres.” This became one of his most famous series which addressed themes of eroticism and violence. These themes were particularly pertinent in relation to the ongoing Spanish Civil War. Moreover, the advent of National Socialism can be felt hovering over the works in this series. In “Massacre,” we see the horrors and violence of war depicted through a wild, raw explosion of lines and figures attacking each other. Through a simple, pared-down approach, Masson captured violence at its core.

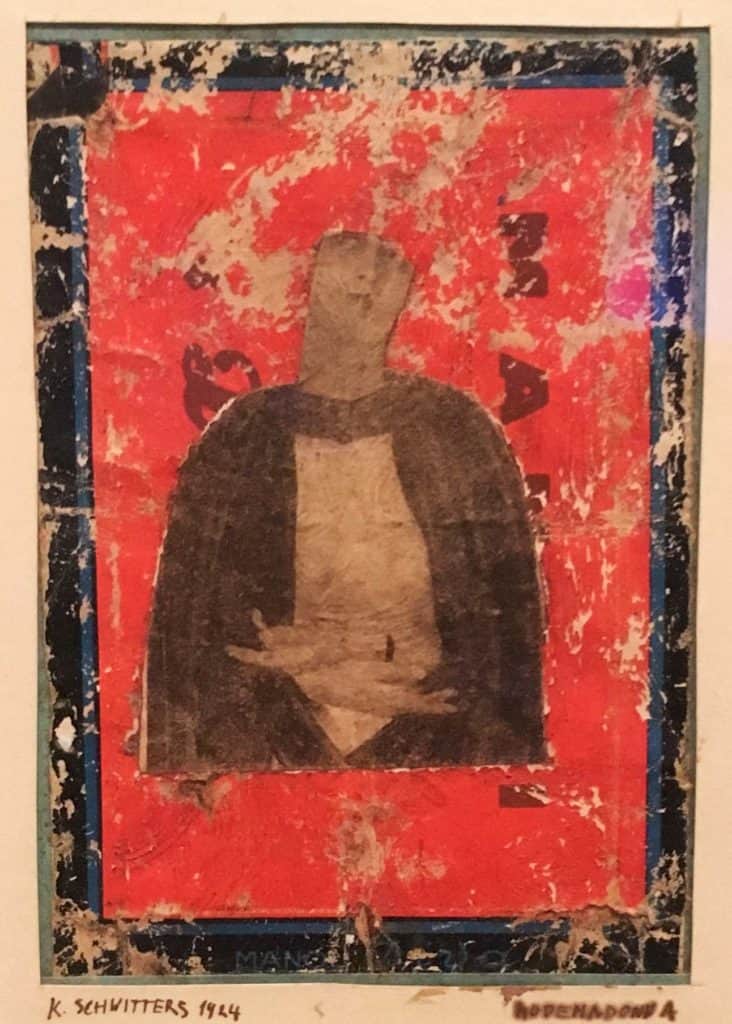

5. Kurt Schwitters, Modemadonna, 1924

Kurt Schwitters (1887-1948) was a German artist who worked across many different genres and media, and was associated with a variety of art movements including DADA, Constructivism and Surrealism. Schwitters is particularly known for his Merz pictures, which have often been referred to as “Psychological Collages,” his spatial construction Merzbau, and his sound poetry, most notably the Ursonate. About Merz, Schwitters once said: “Merz, means to create connections, preferably between everything in this world.” Schwitters’s Merzbau can be considered a type of walk-in collage, which he created in collaboration with other artists and kept adding on to, while also requiring the viewer to assume an active role in the work’s interpretation.

The Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection contains several of Schwitters’s collages, among which is the 1924 work “Modemadonna.” Pasted against a red background is the head and bust of a woman tilting her head as though in silent reverence. Schwitters attached hands separately, which gives the illusion that she is holding her palms up to the sky as a gesture of peace and religious spirituality, while at the same time offering a playful and disjointed interpretation of a familiar holy scene. Schwitters’s Madonna is both reverent and intriguingly against-the-grain, creating a piece that, despite its small size, inspires large contemplations.

Relevant sources to learn more

Visit the Scharf-Gerstenberg Collection

Learn more about Surrealism, Constructivism and DADA here:

Art Movement: Surrealism – Artland Magazine

Art Movement: Constructivism – Artland Magazine

Art Movement: DADA – Artland Magazine

Explore five works at the Museum Berggruen – Artland Magazine