Exhibitions and Fairs

Five Unforgettable Artworks at Museum Berggruen

By Shira Wolfe

“A powerful gesture of reconciliation.” – The New York Times

Museum Berggruen

Situated in the western Stülerbau opposite Schloss Charlottenburg in Berlin is Museum Berggruen, which houses the impressive collection of art dealer and collector Heinz Berggruen (1914-2007), featuring works by Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Paul Klee and Alberto Giacometti.

Heinz Berggruen was a Jewish-German art collector and dealer. Born in Berlin-Wilmersdorf in 1914, Berggruen fled Nazi Germany in 1936, emigrating to the USA. In 1939, he took up a post at the San Francisco Museum of Art, and after the war ended, he founded a gallery in Paris representing many artists with whom he was personally acquainted and whose work he had started to collect. For more than four decades, he worked as one of Paris’s leading gallerists, with a special focus on the prints and drawings of Pablo Picasso.

In 1980, Berggruen retired from the gallery business, aiming instead to focus on expanding his own collection. This collection is housed in Museum Berggruen today. Berggruen returned to Berlin in 1996, bringing his art collection with him and selling it to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation in 2000 for the symbolic amount of 253 million marks, well below its actual estimated value of 1.5 billion marks. The New York Times called this “a powerful gesture of reconciliation.” The museum owns over 120 works by Picasso, offering a broad survey of Picasso’s development as an artist – starting in 1897 all the way up to the 1970s. Other key artists in the collection are Paul Klee, with 70 of his works on display, and Henri Matisse and Alberto Giacometti. The latter two are mostly represented through works from their late periods. The collection also contains works by Georges Braque, Henri Laurens, Paul Cézanne, and a selection of African sculptures.

We feature five unforgettable works from the Museum Berggruen that best exemplify the incredible depth and taste of this remarkable collection .

1. Dora Maar with Green Fingernails, 1936, Pablo Picasso

The Museum Berggruen houses an impressive collection of portraits of Picasso’s lover Dora Maar. They were mostly painted in the same period, around the time that Picasso painted “Guernica” (1937). From one image to the next, Picasso plays with the pictorial parameters, exploring poses and positions, lines, colour schemes, and degrees of abstraction. “Dora Maar with Green Fingernails” is one of the more singular portraits, standing out from the rest due to its very particular style, colour palette and unique amalgamation of both realist and cubist tendencies. Part of Maar’s face is missing, her hair only covering part of her head and her left eye sticking out from a void in her face. Her fingers with green fingernails are sharp and angular, corresponding with the cubist formations of her green jacket. The constant evolution of Picasso’s work is well illustrated by this example, which shows several of his pictorial innovations within a single painting.

In his essay “Constructed Worlds,” in which he discusses the paintings of Picasso and contemporary artist Thomas Scheibitz in the current Museum Berggruen exhibition, Joachim Jäger quotes Bertold Brecht. In 1940, Brecht wrote: “The world going off the rails – that is the subject of art.” He wrote this, of course, following the horrors of World War I, with the horrific events of World War II unfolding at the time of writing. “The world going off the rails” – that sentence is captured in the pioneering segmentation and dissection of Picasso’s art. And at the same time, Dora Maar’s fractured face seems to contain not only the truths of their times, the foreshadowing of one more world war, but also the freedom in art and expression that Picasso embodied.

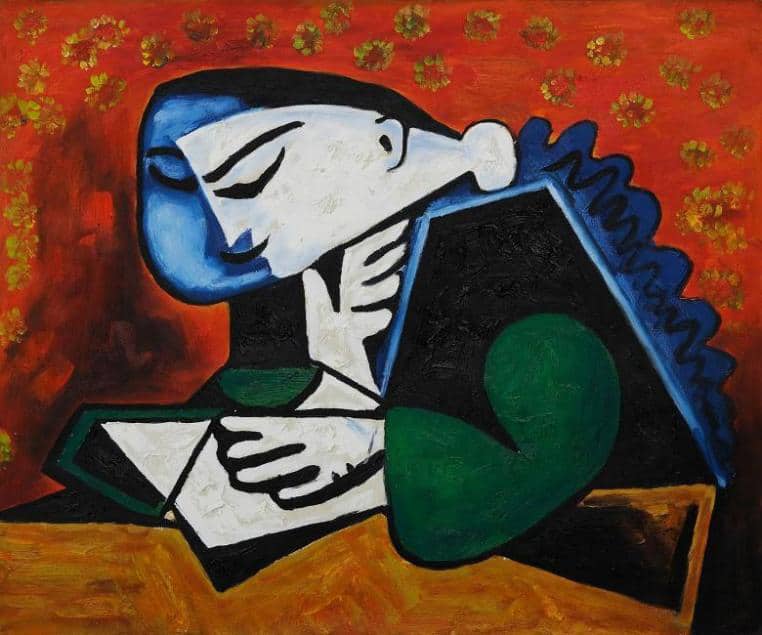

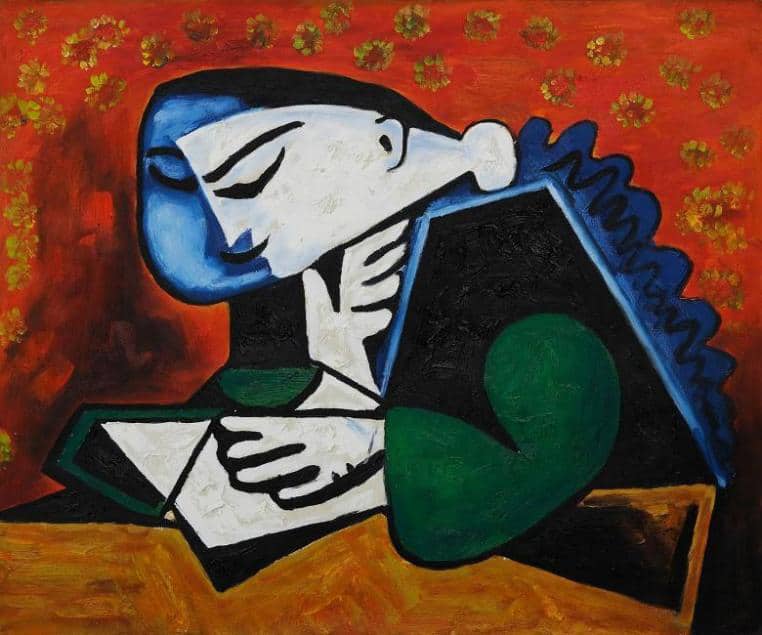

2. The Reader, 1953, Pablo Picasso

Picasso’s personal life took a drastic turn in the ‘50s, when his lover, muse, and partner of 10 years, Françoise Gilot, left him in the fall of 1953. She took their two children, and they only met once a year after that for him to see his children. Throughout the summer of 1953, Picasso had been working on a series of heads and busts of Françoise. It is in this same year that he painted “The Reader,” an evocative painting of a woman reading, set against a backdrop of a red wall decorated with golden flowers. Part of her serene face, eyes cast on the book in front of her, is white, the other part blue, calling to mind the dual nature of people. The painting stands out in the gallery space due to the incredible serenity of the woman’s peaceful and determined concentration and Picasso’s remarkable mastery of colour and form.

By the late 1950s, Picasso’s style went through a new transformation when he took to producing reinterpretations of works by the great masters. He then worked on a series of works based on Velazquez’s painting of Las Meninas, as well as paintings reinterpreting works by Goya, Pouissin, Manet, Courbet and Delacroix.

3. Ships Departing, 1927, Paul Klee

Paul Klee’s paintings range from purely geometrical compositions to concrete representations, such as landscapes or architecture, which are nonetheless composed like a mosaic of many geometrical elements. Despite his advanced theories of form and composition, which he taught at the Bauhaus, he never wanted his paintings to be made solely of completely rigid geometric grids. He strove for his images to develop organically, to grow naturally. Klee was influenced by a variety of art movements, in particular Expressionism, Cubism and Surrealism.

“Ships Departing” is one of three works made by Klee in 1927, covering the same subject matter – “Ships in the Dark”, “Four Sailing Ships” and “Ships Departing” or “Departure of the Ships.” They all use a rocking rhythm that resembles Klee’s diagram of an active line, limited in its movement by fixed points. The series of paintings was most likely inspired by Klee’s Mediterranean trip in 1927. In “Ships Departing,” we see the rocking forms of boats in vibrant colours set against the backdrop of a dark sky, beneath a haunting, large blue moon. On the right is a mysterious arrow, pointing towards something we cannot see, beyond the canvas, a direction of travel or perhaps a destination unknown. Lyrical and enigmatic the work is a masterpiece of Klee’s first fully mature decade of work.

4. Nude Skipping Rope, 1952, Henri Matisse

In the last decade of his life in the late 1940s, Henri Matisse turned a new page in his artistic practice. He was drawn to cut paper as his primary medium, brandishing a pair of scissors as his tool. His new works were called decoupages, or cut-outs. Matisse would colour sheets of paper with gouache paint, and cut out different shapes from these sheets. He then arranged the shapes into lively compositions. This method allowed him to finally work on a larger scale, and to be freer in his approach, by not being restricted to an easel. Moreover, as he was increasingly afflicted by ill health and confined to a wheelchair, it was easier for him to continue to create art this way, with the help of an assistant.

“Nude Skipping Rope” is an outstanding example of Matisse’s series of blue nude cut-outs, famed for their reductive and graphic interpretation of the human form, its various poses and movement. It was produced for a special edition of Verve, the French periodical which assembled prints by modern masters. This edition was dedicated to Matisse’s decoupages.

5. Standing Woman III, 1960, Alberto Giacometti

Marking the 10th anniversary of Museum Berggruen, and his permanent retirement from public life at the age of 92, Berggruen donated Standing Woman III by Alberto Giacometti to the museum in December 2006. The sculpture had been on loan to the museum until then, standing in the Stüler Building’s rotunda where it still stands today, creating a powerful point of entry and exit for visitors. In order to keep the sculpture in the museum’s collection, Berggruen purchased it and donated it to the Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation. He died several weeks later.

Giacometti made several of these standing women sculptures over the years – lithe attenuated and towering figures, haunting with a ghostly fragility and the insubstantiality of their physical forms. He once said: “lifesize figures irritate me, after all, because a person passing by on the street has no weight; in any case he’s much lighter than the same person when he’s dead or has fainted. He keeps his balance with his legs. You don’t feel your weight. I wanted—without having thought about it—to reproduce this lightness, and that by making the body so thin.”

Relevant sources to learn more

Find out more about Museum Berggruen, its collection, current and upcoming exhibitions, and other visitor information here:

Learn more about Cubism, Expressionism, Surrealism, and decoupage/collage art in the following Artland articles: