Articles and Features

Female Iconoclasts: Georgia O’Keeffe

By Shira Wolfe

“If I could paint the flower exactly as I see it no one would see what I see because I would paint it small like the flower is small. So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking the time to look at it – I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

Georgia O’Keeffe

Who was Georgia O’Keeffe?

Georgia O’Keeffe is one of the most significant figures in contemporary art. Known for her large, distinctive flowers and her radiant landscapes inspired by the nature of New Mexico; she made some of the most innovative contributions to American Modernism.

Georgia O’Keeffe is the focus of this week’s edition of our “Female Iconoclasts” series, where we discuss some of the most boundary-breaking female iconoclasts of our time; women who defied social conventions in order to pursue their passion and contribute their unique vision to society.

Biography of Georgia O’Keeffe?

Early Life and a Spirit for Art

Georgia O’Keeffe was born in 1887 and grew up on a wheat farm in Sun Prairie, Ohio. At an early age, she showed an interest in becoming an artist, and her mother encouraged her passion, arranging for art classes. She continued to study art throughout high school and moved to Chicago after graduation to study art with John Vanderpoel at the Art Institute of Chicago, from 1905 to 1906. In 1907 and 1908, she studied at the Art Students League in New York. There, she learned the techniques of traditional realist painting. It was in 1912 that the direction of her art shifted dramatically while studying the revolutionary ideas of Arthur Wesley Dow. Dow’s emphasis on composition and design presented O’Keeffe with an alternative to the realist approach.

For two years, she experimented with her art, while teaching art in South Carolina and Texas. She was searching for a personal visual language through which to express her feelings and ideas. In 1915, she started a series of abstract charcoal drawings representing a radical break with tradition. She sent some of these drawings to a friend in New York, who showed them to Alfred Stieglitz, the acclaimed photographer and art dealer. Stieglitz was the first to exhibit her work, in 1916.

Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz

In actual fact, Stieglitz never told O’Keeffe that he was going to exhibit 10 of her drawings at his 291 gallery in New York. When she found out, she confronted him about the exhibition, but allowed him to continue showing her work. He organised her first solo show in 1917. Meanwhile, O’Keeffe and Stieglitz had started a letter correspondence on a regular basis, sharing thoughts on life and art. They became close, and in 1918, O’Keeffe moved to New York. Stieglitz found her a place to live and work, and also supported her financially so that she could focus on her art. Between 1918 and 1923, O’Keeffe created extremely original and significant abstractions. At the same time, Stieglitz and O’Keeffe fell in love and Stieglitz eventually divorced his wife. O’Keeffe and Stieglitz married in 1924 and remained together until his death in 1946.

O’Keeffe was a muse to Stieglitz, who took over 300 photographs of her. He also promoted her career in his role as an art dealer. However, Stieglitz sometimes exerted too much influence on O’Keeffe’s career. In a 1921 retrospective, Stieglitz showed 45 portraits of O’Keeffe, including intimate nudes. These photographs, as well as the way in which Stieglitz spoke and wrote about the work of O’Keeffe, contributed to painting a picture of the artist as, above all, a sensual and sexual creature. The art critics took their cue from Stieglitz, and upon seeing her works in her first major New York show in 1923, they described her works as expressions of her sexuality. O’Keeffe was shocked and disheartened by these interpretations, and spent a period only painting recognisable objects. Despite this, she gained a great deal of success during the 1920s, and her New York paintings, which combined abstraction with reality and showed her interest in modernist photography, were widely praised.

Experimentation with Perspective

O’Keeffe, inspired by the vibrant modern art movement she was surrounded by in New York, started experimenting with perspective. Her experiments included her famous large-scale close-ups of flowers. One of her famous quotes about her creative process reads: “If I could paint the flower exactly as I see it no one would see what I see because I would paint it small like the flower is small. So I said to myself – I’ll paint what I see – what the flower is to me but I’ll paint it big and they will be surprised into taking the time to look at it – I will make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.”

She was also inspired by New York City skyscrapers, doing paintings like City Night (1926) and Radiator Building – Night, New York (1927). By the mid-1920s, O’Keeffe was recognised as one of the most important and successful American artists at the inception of the modernist period.

“You know, I never feel at home in the east like I do out here. I feel like myself and I like it.”

Georgia O’Keeffe

New Mexico

In 1929, O’Keeffe made her first trip to New Mexico, a place which would completely enrapture her and eventually become her permanent home. The landscape, indigenous art and regional adobe architecture inspired a new direction in her art. This majestic landscape and its unique geological formations, bright colours, clarity of light and exotic vegetation captivated her for the rest of her life. She often painted dramatic close-ups of the rocks, cliffs and mountains, in a similar approach as with her large-scale flower paintings. One of her favourite places was a stretch of desolate hills which she called “The Black Place,” and painted frequently.

O’Keeffe once said about New Mexico: “You know, I never feel at home in the east like I do out here. I feel like myself and I like it.” She would spend the next two decades living and working part-time in New Mexico, part-time with Stieglitz in New York. In 1949, after Stieglitz’s death, she settled permanently in New Mexico. She lived either at her house in Ghost Ranch, north of Abiquiú, or in her house in Abiquiú.

Now, with the freedom to paint in the environment that most inspired her and where she felt most at home, O’Keeffe was able to completely redefine herself as an artist. She could shake the image Stieglitz and art critics had imposed on her that was overly focused on sexuality, and she became known as a mythic figure, “the loner in the desert.”

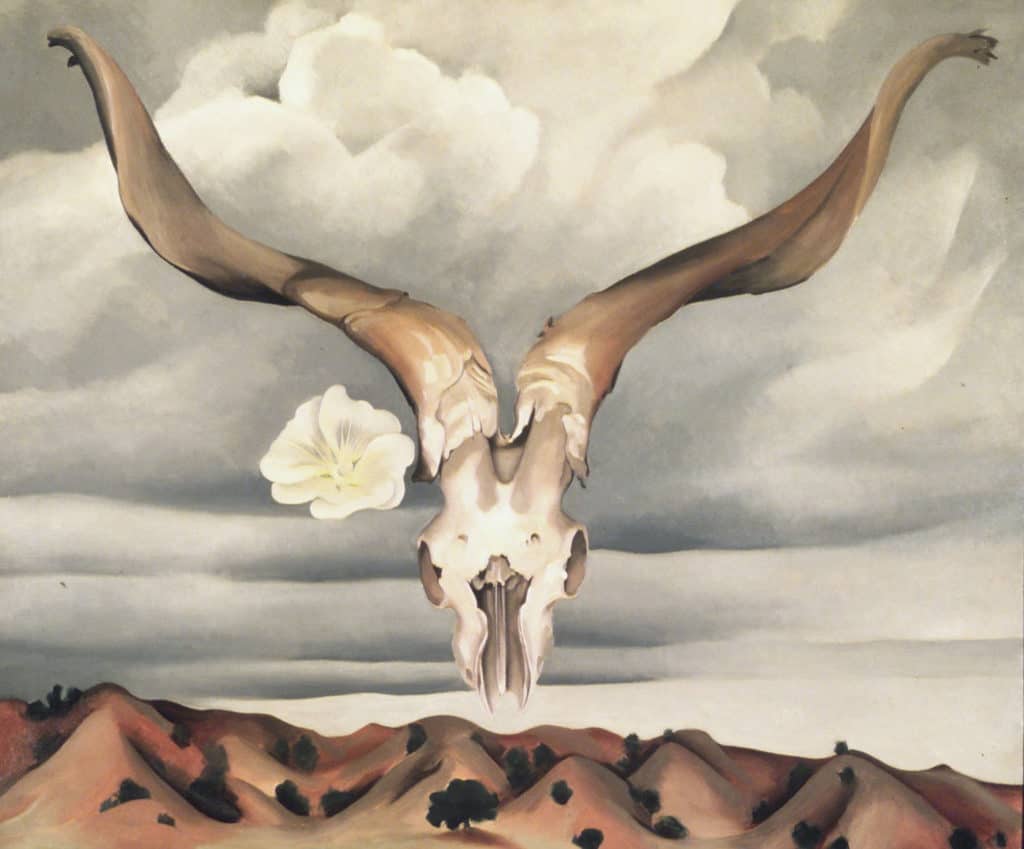

Iconic works from her New Mexico life include Ram’s Head, White Hollyhock, Hills (1935), and Black Cross, New Mexico (1929).

Later Life and Legacy

The 1950s marked a period of significant international travel for O’Keeffe. She painted the grand and spectacular places she visited, like the mountains in Peru and Japan. Her travels took her all across Asia, the Middle East, South America and Europe. When she was 73, she started a new series focusing on the clouds in the sky, and the rivers below. However, she also started to suffer from failing eyesight at a later age and painted her last oil painting on her own in 1972. Yet she never stopped making art. Towards the end of her life, when she was nearly blind, she hired several assistants to help her execute her artworks. O’Keeffe died in Santa Fe in 1986, at the age of 98, and her ashes were scattered over her beloved New Mexico landscape.

Where to find Georgia O’Keeffe‘s work?

The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe preserves the legacy of Georgia O’Keeffe. The museum holds a collection of over 3000 of O’Keeffe’s works and offers insight into the artist’s life, art, and the light and landscape that inspired her work for all those years. The museum also preserves O’Keeffe’s home and studio along the Chama River in Abiquiú, which is open to the public. Othe works are part of collections such as the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., The Museum of Modern Art in New York, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York, among others.

Relevant sources to learn more

Life by Design: Georgia O’Keeffe’s Iconic Style

Discover O’Keeffe’s recipes: The Art of Cooking: Artists in the Kitchen

Georgia O’Keeffe is one among many famous artists who destroyed their own work, find out why here

The 30 Most Popular Modern and Contemporary Artists

Explore the work of other artists from our ‘Female Iconoclasts’ series:

Sophie Calle

Guerrilla Girls

Jenny Holzer

Yayoi Kusama

Shirin Neshat

Yoko Ono