Articles and Features

Art in Bloom: Five Artists Creating Burgeoning Ecologies

Anthony Dexter Giannelli

Exploring Invisible Relationships

The natural world flourishes with luscious life, with glorious activity from the microscopic level; from bacteria and plankton to hydras and the mighty tardigrades play out their tiny cycles of life and death creating the fertile basis for plant life to spread and compete to convert sun energy into something nutritious for the grazers, birds, and humans further up the chain.

Each player, each form of life has a direct or indirect relationship to each other, and vital reliance even to those unliving players in its environment, streams, mountains, geological bodies. All these interactions and relationships contribute to each life form’s individual path of existence regardless of their awareness of each other.

Our society is growing conscious of these vital relationships now more than ever (in modern times at least) and there is no shyness of reactions to these current ecological issues from contemporary artists. Giants such as Olafur Eliasson transport arctic glaciers to the inner city of Paris to demonstrate the interconnectedness of all ecological relationships and our places within the outside world to great effect. Using the visual lexicon of the natural world through altered flora and fauna, another group of creatives reference our common understanding of ecology to demonstrate the vast relationships at play within society and the individual human mind itself: our internal ecosystems.

These artists focus less on an inherent environmentalist meaning based solely on activism, or on drawing a connection to an exact, tangible meaning from the natural world; instead, they use the language of the relationships that is present within natural ecology to express their inner worlds. After all, our human thoughts, minds, personalities are mere illusions of the singular self. We are nothing more than a multitude of connections, our thoughts, the relationship between synapses firing and reacting to stimuli from our environments. Entering these inner worlds can seem as disparate as alien planets, galaxies apart, foreign yet comfortingly relatable, creating a unique experience for each one of us.

Adrián Villar Rojas

Argentine sculptor working on an otherworldly scale, Adrián Villar Rojas’s dystopian, site-specific works create environments in search of belonging which exceed and confuse any context we try to lay upon them. He fills spaces with large-scale, sculptures, a whale in a forest, a crumbling, sleeping giant resembling the David laid on his side, or expansive spaces with glass cube mini environments. In conversation with themselves, these objects rather create a new ecology, a new ecosystem where it’s the search for meaning that feeds all connections, instead of the nourishing solar rays that feed our natural ecosystems. Here the works blossom through each relationship that exists between each individual object; thriving as isolated life, that seemingly exists in a space protected from the context of the viewer and their world.

In his most monumental work Theater of Disappearance, taking place under four instalments of major installations, across locations laden with contexts such as the ancient National Observatory of Athens, the Met, or an artificial seabed, audiences traverse impactful terrains where internal mindscapes are brought into existence. Painted with glass cubes containing separate, closed-off elements like fragments of a larger story, the relationship between each instalment, each environment, each sculpture pushes the narrative deeper into the artist’s consciousness. Each cube resembling aquariums or terrariums contains plant, animal, or man-made artefacts frozen together, in search of their place in time and space.

Yayoi Kusama

A true native to the natural world, Yayoi Kusama‘s floral excentrism is no stranger to the loving embrace of the general public gaining a cult-like following that extends far beyond the normal boundaries of the art world. Particularly known for her installation works, selfie-conducive infinity rooms, and a visual world populated by a pop-art oriented use of colour and patterns, her internal landscape bleeds into a multitude of mediums. Heavily influenced by the visual memory she forged at an early age through life on her family’s seed nursery, the familiar forms of pumpkins and tulips take on animated roles in Kusama’s visual lexicon. Although originally trained in a more traditional style of Japanese brushwork, her early works focused heavily on depictions of single branches, leaves, flowers, insects, etc. After venturing on her own to the sexual revolution environment of 1960s New York, her practice grew to performances, wearable art, and expansive installation-based environments.

Through the safety and structure of a voluntary commitment to a physiological hospital, Kusama explores an inner environment teaming in life with blooming soft sculpture, sentient microorganism reminiscent forms, and altered botanic beings. Each form, whether three-dimensional sculpture or on the two-dimensional canvas seems to be in constant dialogue and coexistence. This intrinsic connection to the ecological comes to life like never before in Cosmic Nature at the New York Botanical Gardens. Presented together with its natural counterpart, the works transcend objectification as viewers walk a visceral line between two distinct botanical worlds. References grow to pay honour to patterns, from the patch-like groupings on the My Eternal Soul canvases mirroring the real world flower beds, we see connections throughout her body of works, not solely the figurative giant flower and pumpkin sculptures.

Arnaldo Roche Rabell

The late Puerto Rican portrait artist, Arnaldo Roche Rabell was a trailblazer in expressive, structurally flowing representation on canvas, often leading to his inclusion amongst the expressionist or neo-expressionist movements. However, a deeper look at his visual and textural languages reveals a myriad of techniques that extend from the normative oil on canvas tradition and show a creator based much more in the ecological world of his home island than that of the 19th-century European expressionist masters. Through the use of collected plant life, wood shards, or nautical remnants, Roche Rabell utilized frottage, collage, and grottage to embed the turbulent relationships of the natural world into retellings of his life story, loss, movement, and a deep emotional world burgeoning to life under the surface.

Often referencing the destructive but life-bringing forces at play in the natural world where seemingly isolated pockets of land are surrounded by the unforgiving and omnipotent forces of the ocean, Roche Rabell’s artistic world reminds us of our mind’s island in the sea of humanity. Immensely heavy, emotionally laden vignettes celebrate life, the religious, and the existential. Bringing the literal natural world onto his canvases through native leaves and flowers each inspiring form builds up to a greater meaning. Roche Rabell has expressed that through his creative process he feels more connected to a divine being than to his subconscious mind, creating surfaces whose connection to nature seems to run as deep as consciousness itself.

Claudia Comte

As an explorer of artistic landscapes, Claudia Comte’s practice and recent exhibitions, including her current How to Grow and Still Stay the Same Shape at Castello di Rivoli, revolve around a deep understanding of the ecological world. Growing up in a chalet in the Swiss Alps, surrounded by forested mountainous biomes, the connections and relationships of the natural world resound with her internal way of thinking. Honing in on the ever-present and changing patterns within nature is the point of departure for her visual and material language, whether in the form of literal visual patterns or displayed through the relationships between its many actors. Through her investigation and translation of the networks at play within nature and society, her practice spans influence from woodworking to the glacial movements of the Neozoic.

In her 2019 exhibition I Have Grown Taller from Standing with the Trees, Comte lays and hangs tree trunks stripped of bark across a gridded carpet, representing the subterranean network through which each singular tree is connected. Invisible from the surface level, unassuming root systems and fungal mycelium networks connect seemingly isolated beings, just as in anthropological events. Virgin wood plump with humidity takes shape during the exhibition and through active interaction between natural structures and human visitors. The structures move with the environment, the carpet stains, and soils from interaction with the weather, and we are made to ponder our influences and connections of our actions. We can contemplate our roles within the greater system; do not invent anything, mathematics and the seemingly artificial language of geometry are already existent in the earth.

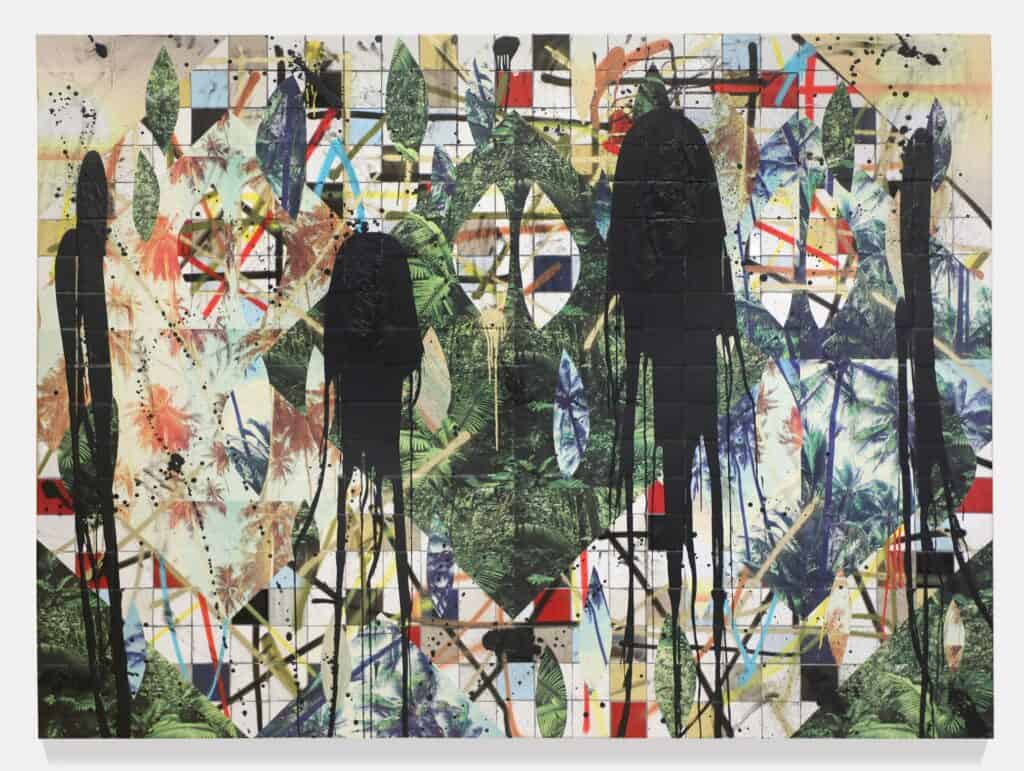

Rashid Johnson

Though displaying a deeply personal exploration, Rashid Johnson’s practice brings to light the many glorious and toxic societal connections in play throughout modernity. Originally from the northern concrete-clad land of Chicago, Johnson’s visual world contrasts the hard industrial with soft, natural, lush palm trees covered in dripping African Black are a common theme within his work, referencing the luxury and prosperity that palm trees represented to him during his youth. Expanding from representation to physical presence in larger works such as Antoine’s Organ, Johnson places a young pianist in the centre of a gridded steel structure surrounded by potted tropical plants, films, shea butter, and cherished literature. The overpowering visual element, the potted plants come together from different geographic and ecological regions, transplanted with the safety and reliance of their individual pots into an alien environment.

His work not only inhabits the protected human environments of exhibition halls but also extends its presence to the natural world opening up to the objectification to the forces of nature. Johnson has expressed his willingness and excitement for this interaction, to see his work overgrown and overrun by the environment. In his showing No More Water at Lismore Castle Arts, his structures sat in open-air gardens, where birds consumed the shea butter resting upon the steel shelves. Shea butter also holds a special place in his internal world, recalling childhood trips to West Africa buying shea butter to bring home, applying the moisturizing botanic on his skin, applying the theatre of Africa to himself. We see the dual fragility and resistance of our socially constructed theatres, exploring the theatre of socially constructed reality within the context of the natural world.

Relevant sources to learn more

A Journey through Bio and Eco-Art

Environmental Art: Changing Our Habits Or Just Illustrating What We Already Know?