Articles and Features

New Thoughts on Ugliness. Information, Visualisation, and Hans Haacke’s Dream

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Volume 18

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in a recent standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

Today, in the summer of 2021, the tenor of the conversation behind the scenes in the world of art dealers, auction house specialists, advisors and speculators is not primarily about art schools or movements or scenes. It is not about the messy front lines of aesthetics and the bubblings of tomorrow’s culture. It is at this moment about the filigree of finance, spread bets, abstract lateral moves, consolidations and takeover bids, the sorcery of analytics, and the rat’s nest of subscribers-only insider info. It is calculation and gambling and warfare. This is for sure a symptom of not seeing art or art people in person, as it has been for the past 18 months, but this is also not new or shocking. The story of both art patronage through time immemorial and the specific late 20th-century thing known as the art world is a story written by, for and about rich people. Therefore it’s always somewhere about money. Gamesmanship and the accrual of wealth have always been part of art collecting, because consuming art is a luxury: you have to be able to afford it. This is a basic tenet of top-down society, and there’s nothing, short of revolution, that one can do about it. I accepted this aspect of life in art many years ago and if you’ve made it this far, you should too. Nevertheless, the specific current power conversation around art — the market as a private equation to be solved — is novel in its ugliness. German-born American artist Hans Haacke’s MOMA-Poll (1970) will help us understand exactly what makes it so ugly.

MOMA-Poll was shown exactly once, at Information, a group exhibition presented in the summer of 1970 by 35-year-old associate curator Kynaston McShine during the first swells of his famous four-decade run at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. It was an exhibition urgently of its time, with 130 artists and groups whirring in the galleries, meditating on what we know, what we want, and how to spread that message to other people. Information was animated by the expanding catastrophe in Southeast Asia and a turbulent domestic climate made flesh by the Ohio National Guard’s murder of four Kent State students protesting the war earlier that spring. Texturally and spiritually, the show’s collage aesthetics shared much with the emerging field of semiotics and its snappy, electric cross-disciplinary feel, networking ideas together per Marshall McLuhan, the first techno hippie, as well as the Independent Group and the ICA’s expansive multimedia themed 1950s exhibitions in London, which predated the high-low of Pop art by a decade.

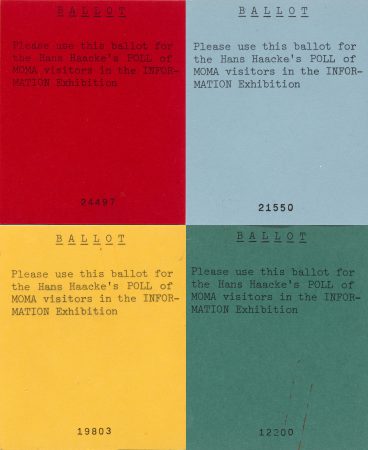

MOMA-Poll began when visitors to the exhibition were given ballots upon entry. The work comprised two thigh-high transparent plexiglass boxes with slots in the top, and a sign. The sign, brought in by Haacke the day before the exhibition’s opening to avoid vetting by the museum, read “Would the fact that Governor Rockefeller has not denounced President Nixon’s Indochina policy be a reason for you not to vote for him in November?” If yes, the sign asked the viewer to cast their ballot in the left box; if no, the right. The man in question, Nelson Rockefeller, was a New York politician who would in four years be the Vice President, and he sat on MoMA’s board of trustees. By the end of the exhibition, the boxes clearly showed double the votes damning Rockefeller’s silent complicity with Nixon’s overreach. MOMA-Poll was a considerable embarrassment to Rockefeller, a proud patron of the arts. His brother David — the chairman of MoMA’s board at that time — fired the museum’s rookie director, John Hightower, a year later. MOMA-Poll had been a factor in his ousting.

MOMA-Poll’s will forever be one of the foundations of what is now known as Institutional Critique, a method and a philosophy that has been taught for 50 years and is positively booming in culture at large in 2021. MOMA-Poll is an emblem, and it will serve art history well. Hans Haacke is 84 and living in New York City. He has made work, much of it significant, this whole time, and he has never not been relevant. In 2019, in our own era of protest and rage, the forced resignation of Warren Kanders — the Whitney board vice chairman who owned a company manufacturing weapons and tear gas used for dangerous domination in protests and at the US border — was a moment, a movement, that might well be considered a realisation of Haacke’s long-ago dream. The outrage against Kanders started with 95 Whitney employees expressing their misgivings about a powerful man by making themselves visible and being counted. Their visibility heightened awareness, and within 8 months the dissenters were numerous enough to make a difference.

Let us acknowledge that MOMA-Poll is unscientific. Empiricism is not its gift to society, and this is a fact that often gets lost in its clean execution. “The results cannot claim to meet professional standards” was Haacke’s charmingly desiccated comment to Artforum editor Tim Griffin as they discussed the work in 2004. MOMA-Poll reached a narrow demographic — the overwhelmingly liberal, white, middle-class milieu of museumgoers in 1970 — and it was not supervised. Documentation of the boxes show bits of paper that definitely aren’t ballots stuffed in there. It was in an art gallery; one should expect nothing less. Yet it is in those piles that we may take heart, and in those piles that we may return to today’s climate of deeply abstract mercantile manoeuvres in the art world. The piles may not do anything, they may not comprehensively conclude anything, but they do serve as a reminder that reality, at its most basic level, is tied to evidence. The confetti of coloured paper penned inside plastic cuboids is an illustration of real people making real decisions. Evidence is an anchor, even if its worth cannot be perfectly quantified.

At the very bottom of every page on the website of Frieze, the magazine cum art-fair behemoth, sits a statement both quiet and loud, in all caps but also 8-point type: DO NOT SELL MY PERSONAL INFORMATION. You can click it, and apparently they’ll stop selling your personal information. It’s astonishingly, almost amusingly direct, and the phrase stands out every time I come across it. “If something’s free, you’re the product” is a 21st-century truism that is also true, but there’s more here than chilly Orwellian misery. It’s the opacity that hurts. Who’s selling what, and to whom? Clickable statements at the bottom of websites aren’t in the business of letting you see for yourself. They just want you to agree or disagree. One becomes aware of how little one sees and knows.

The shenanigans of an ever-more engineered art world are ugly because they lead us away from looking, inquiring, and testing out ideas in the real world. As a worker in the art industry, it would be disingenuous for me to shit on however anyone has figured out how to make a living these days, but this art-as-calculation doesn’t feel right. It doesn’t appear to have anything to do with art. Art isn’t maths and statistics. MOMA-Poll urges us to take what we can see as a proof of humanity, a proof that the visible world is an energizing force for good, and that art is the great way to express this energy. MOMA-Poll is not a fact, nor was it ever an effective political tool, but it remains a reminder that we have eyes and voices. We can use those voices and trust those eyes and can change the actual world, not just numbers on a page and bank balances.

Relevant sources to learn more

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol.11 : Halfway To The Future. Saatchi Yates’ Proposal For Tomorrow’s Art Gallery

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol.12 : The Body Won’t Quit. Finding a Way Through 2021

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol.13 : Thomas Hirschhorn and Our Life in Ruins

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol.14 : A Mellowing Dictator. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Jonathan Meese

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol.15 : Yours For the Taking: Justine Kurland’s Continuing Story of Freedom in America

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Vol.16: Cooler Heads. Yue Minjun and the Lessons of the Recent Past