Articles and Features

The Body Won’t Quit.

Finding a Way Through 2021

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Volume 12

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in his last standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

The good people at Artland have asked me, as is customary, for my thoughts about the year ahead in art. It is an amusing conceit for 2021, forecasting the future, at a time when reality twists as the world turns. We need only consult today’s news. A few hours ago, in a courtly, long email to its exhibitor network that landed on the news wires a few hours later, the directors of Art Basel announced that they were planning to go ahead with their Hong Kong edition in late May, having earlier postponed it from March. Great.

There were no comforting particulars provided about how it would go ahead, just that exhibitors would have ‘options’. The directors follow up a paragraph later with the news that the mid-June fair in Basel, the 50-year-old citadel of the whole art biz, would move to September. Though sluiced through layers of PR, the email is straightforward and spoken clearly. Yet, tellingly, there is no lede to this letter: it isn’t clear what it’s about, or what and where the news is. And here is the puzzle of the art world 2021, embodied in pristine yet inconclusive corporate messaging: nothing can be said for sure about how this year is going to go. In some ways, it’s foolish trying, because everything will have changed tomorrow.

In trying to forecast where art is going and wonder whether and how we’re going to make it, I am obliged to remember moments when art stopped, or fell apart, where some edifice of the art world flopped over and couldn’t be propped up again. I thought back, and got stuck on a moment, in the 2015-2016 season, when the bottom fell out of the abstract painting market.

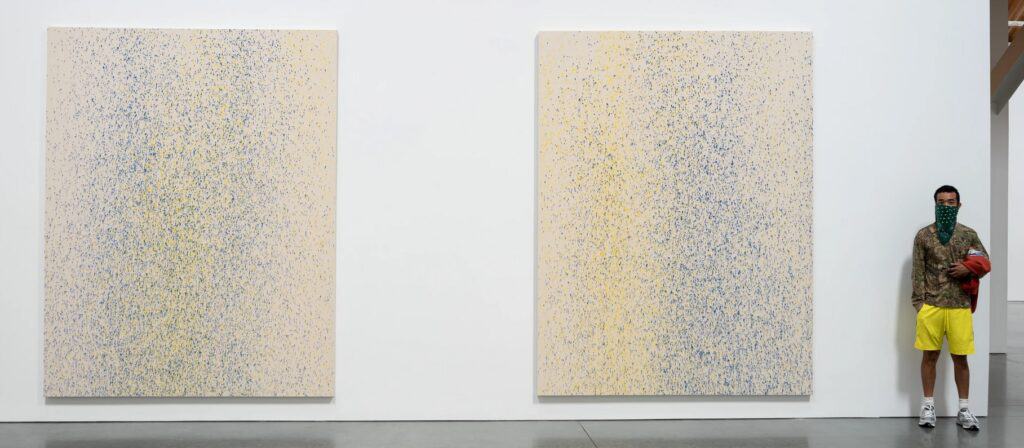

The western abstract painting market of the 2010s was a journey to the end of a style.

As both forebears and canaries, painters such as Sterling Ruby and Joe Bradley tested a hands-off mentality in painting in the 2000s, creating a brew of exacting vagueness on the canvas. Twombly without the geekiness, Morris Louis without the joy, they teased artworks into being. It was both gentle and bold, a tough light touch, which was great for male painters at that time. (There were a lot of male painters at that time.)

At the end of the decade this attitude toward images and image-making crossed paths with the insurgency of screens, which changed our relationship with objects as it flattened information to lit rectangles. This real cultural shift fit perfectly with abstract painting, which went further into the diffidence of making art, pursuing effects that were more and more impassive, paintings that were more and more general, averaged-out.

Do less for more impact. Abstract painting’s embrace of the deadness of smartphones created a self-generating loop, where by 2014 it had become difficult to know where abstract painting stopped and where its consumption on screens started and — most of all — where its meaning resided. This symbiosis hit home for me that spring when a young gallerist, encountered by accident in a walkup gallery complex in Berlin, pointed out that the paintings in her show were slight vertical rectangles because they look best on an iPhone in that format, and though it wasn’t at all intentional, it was undeniably why the artist had made them that way.

In 2014 the prevalence of this type of art was so obvious that a backlash had to come. Fairs were so stuffed with the art of approximation that it was like wading through caramel, all gluey matter, no payoff. The auction results read like magical realism, a silly parallel world conjured into being by the falling hammer. There grew a brisk trade in think pieces lancing this type of painting in the press, often tying it to the phenomenon of soulless art flipping that was also then in vogue. And it got a sobriquet that stuck, Zombie Formalism, via critic Walter Robinson. At this exact moment, amusingly, big galleries bet on this work and inflated its prices into routine six-figure sums. The scene became messy and ludicrous very quickly. In one season, first at the auctions, then at fairs, and then in galleries, this school of abstract painting went away.

A school of art evaporated because it could not keep up with the period it defined. The promise of the new uncanny abstract was that it could be enchanted, and would reflect the cultural and technological moment by being ‘generated’ more than made. But culture and technology were moving on a different wavelength, and no amount of intellectual justification could trump the fact that people weren’t interested in looking at pictures that didn’t feel like our changing lives. Screens had become less joyful, and the paintings looked a lot less glamorous. Art and our evolution often occur in sync, but when they don’t, the art looks passé, just like that.

Everyone’s recovered since then, and this whole moment is more of a footnote than I am making it out to be here. I do wonder where all those paintings went, but they cast little shadow over our present day. And I do believe that there is a lesson and a message of empowerment that can be drawn from this story as we confront the months ahead.

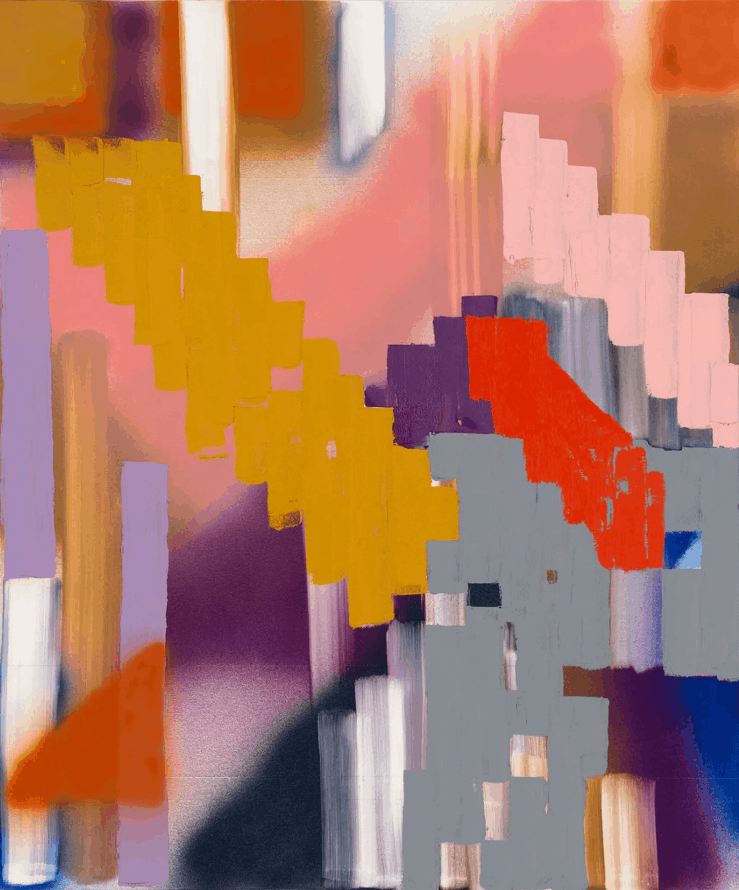

Figurative painting arrived after abstraction’s demise. Like clockwork, one craze gave way to another. It has been a joy to see the figure be so febrile, its limits tested. Artists have had so much to show and say about the figure in painting over this era in progress. The paintings of Nicolas Party, Julie Curtiss and Emily Mae Smith have a boneless fluidity and odd taste, taking in the stretch and kink of the body from the Chicago Imagists to Erte as they see what it can do. Geometry and iconography are baked into the precise forms of Leonard Hurzlmeier or Derrick Adams, creating visible building blocks for fully rounded humans. Ridley Howard makes everyone cool, while Amy Sherald pushes coolness past its most comfortable point to a place of unearthly, magisterial austerity. Aliza Nisenbaum paints people and their lives with the low-key specificity of 1970s Hockney, except prouder. Aaron Gilbert paints in the vernacular of American Social Realism, rendering struggle as a universe that envelops his subjects, colouring them. Lynette Yiadom-Boakye is in the business of inventing real people through imagined portraits, thus pointing to the power of tapping shared history. Alistair Mackinven paints spectral characters that are both avatars of spooky 19th-century symbolism and seekers in today’s darkness. Robin F. Williams — and the broader work of her New York gallery, P.P.O.W. — manages to animate femininity so that it radiates.

These are the first painters that sprung to my mind. After 20 painters there are another 20 painters. Indeed, I work as a dealer with several painters at the boundaries of the figure. New painters appear on a weekly basis as manna for fast-paced discussions. Stars are made very quickly. My inbox is full of paintings of people. It’s a glut. And I am only speaking to the art made inside my orbit. It’s everywhere.

Yet I do not feel that this moment of popularity is a moment of saturation, a passing trend, the result of a reaction that will be replaced by some other reaction and chalked up as a chapter in modern art’s endlessly evolving history. The body today is the body politic, a place where our collective identity is forged through depictions of race, gender, sexuality, opportunity and otherness. Figurative painting is everywhere because it is vital and it feels like us, and it has miles to go. At a moment when the most powerful corporation in the art world cannot directly tell us how we are going to get back to our lives and livelihoods in art, it is intensely reassuring to believe that art can hold genuine promise, and that nothing can stop its progress. Not everything is a trend, sometimes it is a movement. I will be looking at figurative painting in 2021, and letting it carry me wherever it’s going, wherever we’re going.

Relevant sources to learn more

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.6 : Dirty Work And Pure Intentions

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.7 : Rising From Slumber: Narcosis, Creation and David Hammons’

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.8 : Palace Intrigue

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.9 : Accepting Alchemy through Bruce Nauman and the global pandemic

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.10 : Working Through A Daze With Dana Schutz

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.11 : Halfway To The Future. Saatchi Yates’ Proposal For Tomorrow’s Art Gallery