Articles and Features

Dirty Work And Pure Intentions:

A Moment In A Crisis

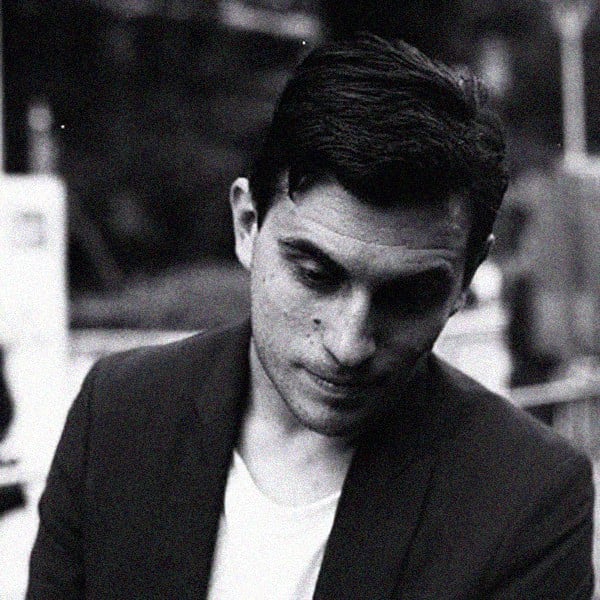

William Pym

Standards & Practices

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in his last standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

Knoedler and Co. was the first mega-gallery. Founded in 1846 in New York, by the turn of the century it was operating multiple galleries in London and the United States. At this point, like today’s mega-galleries with waystations around the world, they were flicking treasures from place to place. Deeply enmeshed in wealth, in 1930 the gallery served as a key broker in Andrew Mellon’s secret purchase, from Stalin, of 21 masterpieces from the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad. These works form the core of the collection at the National Gallery of Art in DC. They continued to push weight, selling one of the three versions of John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark (1782) — a truly terrifying, truly singular painting — to the Detroit Institute of the Arts. This alone is worthy of the history books. They had issues with paintings that had been stolen by the Nazis, but there is no great question that they operated in bad faith, and works were returned to their owners. A lot of this happened in art dealing after the war. Their finances got a little screwy in the ’70s after Armand Hammer bought the business and the last family members retired and died, but Knoedler & Co. stayed rich, if not influential, in the postmodern era and on. Through the 2000s they got into increasingly hot water selling forged Modernism, Pollocks and Motherwells painted in a garage in Queens, for millions of dollars. The gallery closed abruptly, permanently, in November 2011 after 164 years, as the lawsuits related to duff sales piled up.

This narrative came to my mind during this solitary spring, at a moment when the art world has been shaken to its core. Knoedler is an example of a business that believed in staying powerful, to just keep doing it like they’d been doing it. Consolidating power for multiple generations, cornering the market to the point where you can just do whatever you want and barely take a ding, is the way that real wealth accumulates. As you get richer, you’re buoyed by other rich people, creating security and influence that lasts. Knoedler just kept going, generation after generation, untouchable. This is the modern aristocracy.

Knoedler is the standard bearer for an art business that relies on resources, the free flow of resources, that is at its apogee today. The most successful galleries swim in resources — and the latest generation of mega-galleries are living it up like it’s Knoedler in the 1890s— while the smaller and younger galleries patchwork resources together, season to season, artist moment to artist moment. This second group is between 80 and 90 percent of the art world, FYI. At this moment in time, by which I mean today, right now, everyone has the same resources. The art gallery world currently only exists in one space, behind a screen, and every gallery has the same reach. There is no bar for entry, no financial ante. This sounds like a meritocracy. Gosh, this would be a different art world.

And it won’t last, of course. This is a daydream, a moment in a parallel reality. Order will be restored. As soon as we’re out of the house, the powerful will reestablish their position as leaders; they’ve been working on it for weeks already. But there remains something tart, and appealing, in tasting an art world where success and longevity were no longer guaranteed to the kings and kingmakers. Imagine what art might arise from this moment, with no rules, no legacies, no authorised standards of quality.

” Crawford depicts subjects with all the passion he has, and you can feel it.”

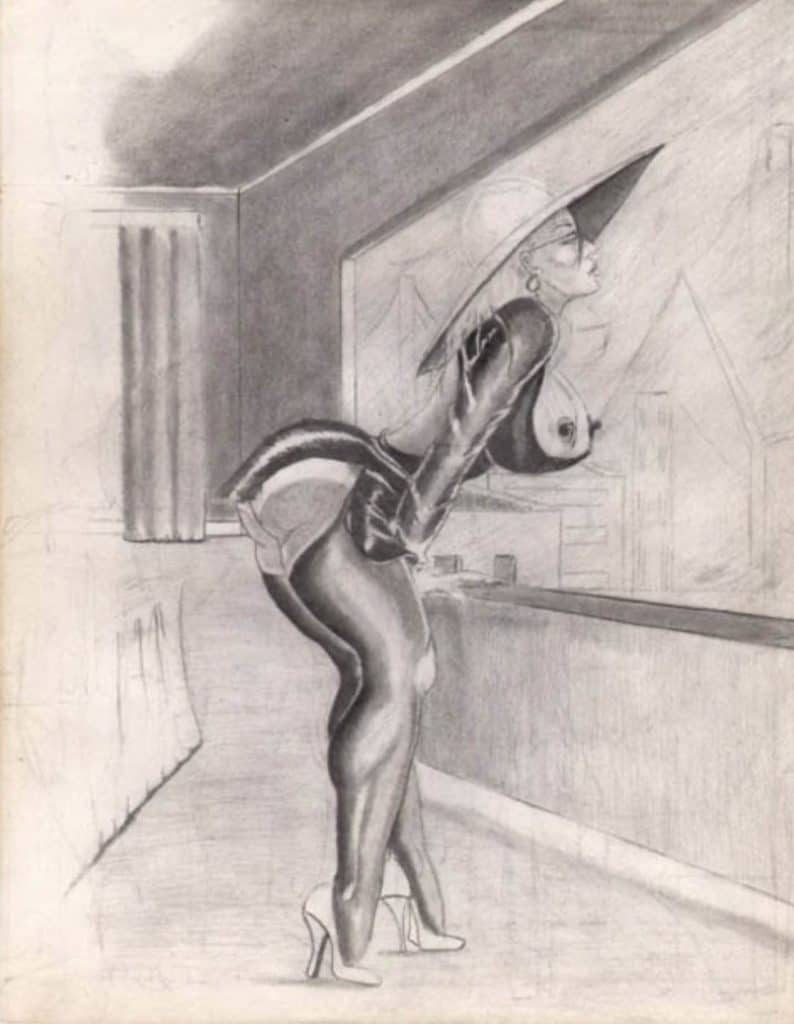

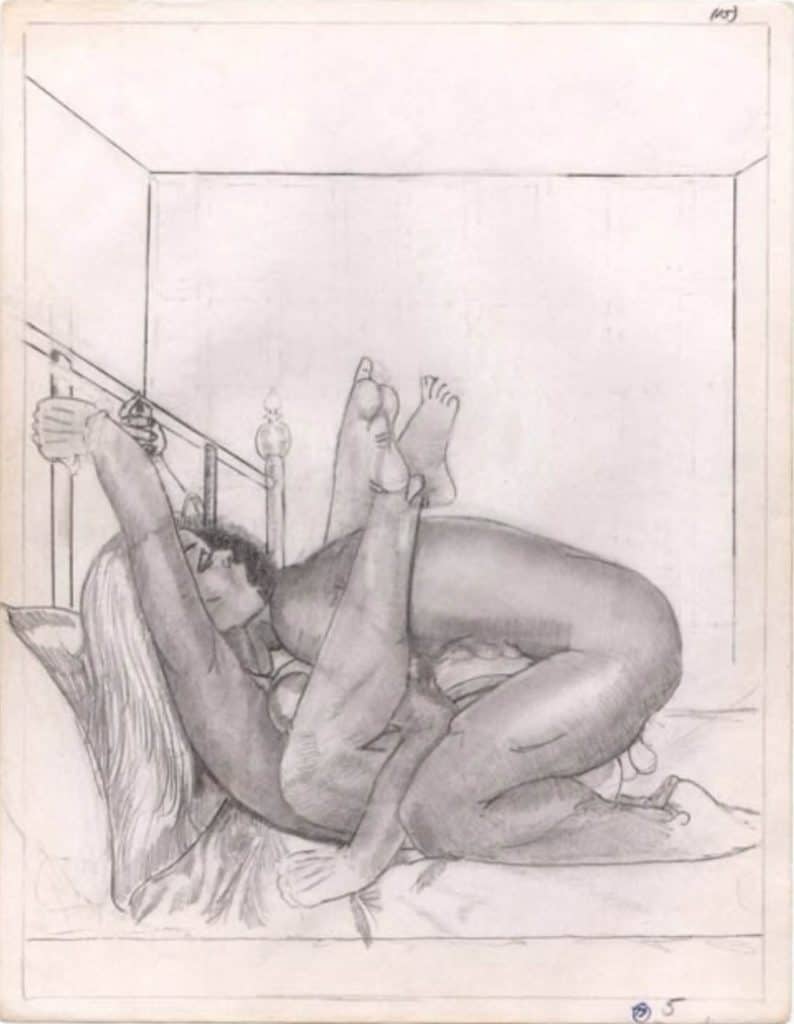

In 2015, I became very taken with a body of 950 drawings by William Crawford. Crawford’s archive was found in an abandoned house in Oakland. His name is known because he signed some of his drawings. Crawford may have been in jail for a time, since several works are drawn on the backs of prison rosters, dated 1997. The look of his characters’ hair and dress suggests Crawford had come up in the 1980s or late 1970s. Crawford drew graphic pornography with shading as delicate as a cloud, dramatic hard-pencil perspective, and a flair for human sinew evocative of an Academy acolyte of anatomy and life drawing. I am no bigger a devotee of erotica than the next person, but I was immediately drawn to the inventiveness of the work, its relentless pursuit, its energy. In this artist I saw an immediate proof of life. The fact there is also biography of this artist that we may never invites mythologizing, but we also don’t need more than what is on the page. Crawford depicts subjects with all the passion he has, and you can feel it.

Crawford’s work ended up in Portland, Oregon, where it was archived and documented, then published into a book, by the excellent gallery, bookstore and art book publisher Ampersand Gallery. Certain details remain foggy to an unsatisfactory degree about Crawford’s discovery, such as efforts made to find the artist or his family members, ownership of this estate, etc. The work got around for a few years, to Zieher, Smith and Horton in New York and Delmes and Zander in Cologne, who showcased the work in a guest slot at David Zwirner in Chelsea. Things went quiet; Ampersand killed the page on their website showing available works. The book is out of print. One has to wonder what happened. Sometimes art gets hidden away; his family may have been found, or come forward. Prison records would yield something, you’d think. We certainly deserve to know more about the state of William Crawford’s art.

One could return to the temporary fantasy of the meritocratic art moment, with all things being equal, and art ready to be found, with power being meaningless, and quality standing alone as a measure of worth. What art will be loved, and why? William Crawford may be singular in the particular thing he does, but he’s far from alone. He ranks among all the art whose purity pierces through, art you can count on. John Singleton Copley’s deranged painting of the translucent kid about to get eaten by the alien shark on the taffy Atlantic pierces through too, no matter the Knoedler story.

While the dream of equal opportunity may dissipate with the virus, we may remember that art with a purity of heart always has a chance.

Relevant sources to learn more

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.2 : Kalup Linzy

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.3 : Maurizio Cattelan

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.4 : Amalia Ulman

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.5 : Notes From The End of An Art Market