Articles and Features

Working Through A Daze With Dana Schutz

William Pym

Standards & Practices Vol.10

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in his last standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

Virginie Despentes’ 2006 extended essay King Kong Theory — recently republished in a bright new translation by Frank Wynne — is a French punk feminist memoir and treatise on sexual violence. It is short and clear, you can digest it in three sittings; I would call it essential reading. Despentes writes from a place of trauma, defined by a traumatic experience, and spends King Kong Theory peeling back everything it means, working in reverse. “The problem with porn is that it affects the blind spot of reason,” she writes. “It directly targets the centre of fantasy, bypassing language, and even thought. First you get hard or you get wet, only afterwards can you ask why.”

To be dumbfounded, or overwhelmed, for life to be punctuated by shock and only afterwards can you ask why. This idea resonates in 2020. Life is a clatter of information or a punch to the gut, and either way you’re seeing stars. At this exact point in time we’re scrambling, a little stunned, to figure out what happens next.

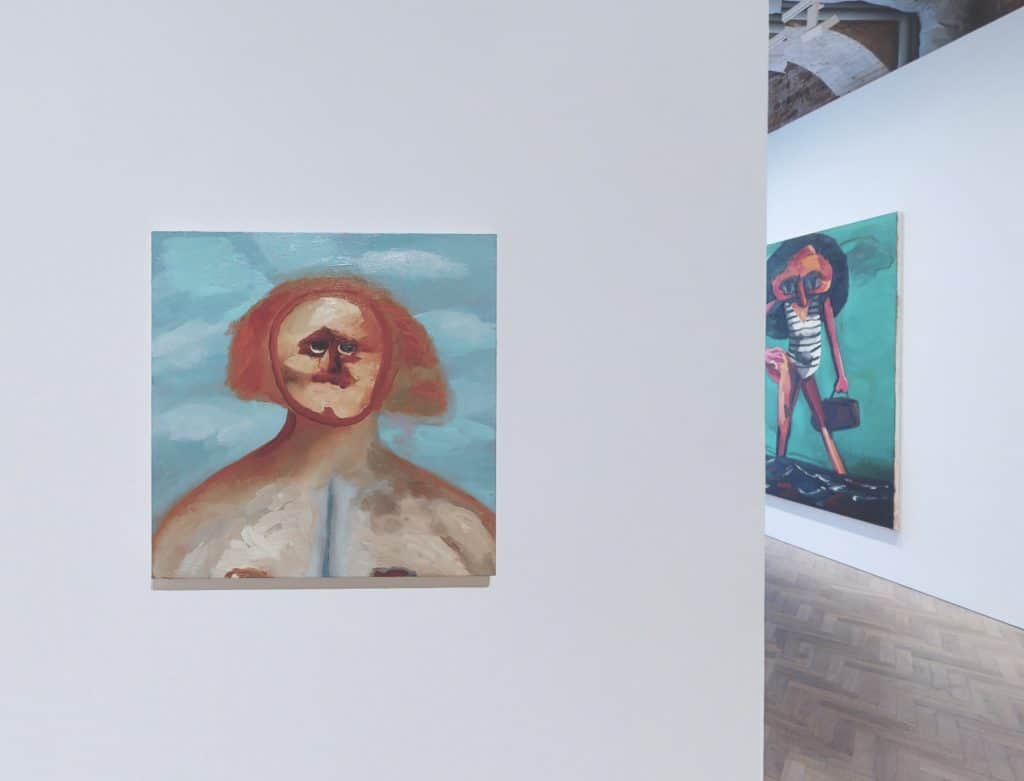

This is the geopolitical backdrop to the first London show of 44-year old New York painter Dana Schutz. It is surprising that this show is Schutz’s UK debut, because she is a superstar in the art world: her artist peers and art students have long admired her, and institutions admire her, and the wacky contemporary blue-chip market admires her. This show brings a pleasing bit of heat and energy as London turns grey. Pleasingly, too, Schutz’s painting has never made more sense, or seemed clearer, than it does now.

Schutz paints figures. They are often extended or extruded, squeezed together or reduced to one feature, but they’re always there. All the paintings have subjects. The large group scenes, by nature of being large group scenes, tend toward allegory and social commentary. The single-figure canvases relate more to classical portraiture. They brim with content. The figures wear the world, they’re wrought and weary and most of all incredulous, unbothered by the fact that everyone around is a cranium, or that some figures have reptile and bird features, or that there are giant band-aids flying through the scene. The only clear expression in the exhibition is the smile on the man smoking a cigarette on a rowboat in the dead of night, squashed under a cornucopia of giant heads in the huge inky expanse of Boat Group, and he’s suspiciously beatific. No one is explaining what’s going on, there are no narrators in these paintings, no helpful wanderer at the foot of the composition pointing to the waterfall. Schutz’s painted world is a precarious place, sometimes misshapen, sometimes spindly or sore, a little painful-looking. As viewers we cannot situate ourselves; we are far from home, maybe far from earth.

Schutz takes to these scenes and these characters the only way one can. She stabs at the canvas, showing the decisiveness required to form a wild composition. She dissolves into illegibility as she figures out what’s going on, and this becomes abstraction, a different discipline. Iconography stacks up via the eyeballs, jawbones and skulls, the scarred sky, the piles of heads, the bubbles in the foam of a breaking wave, but a single storyline doesn’t come together from the pieces. The paintings are both manic and thorough, provisional and certain, with an abundance of technique. Passages of painting are gestural abstract expressionism, parts are formally worked for calibrated impact. Paint can die on the brush, halfway through its journey — the strange brown circle inscribing the face of Neanderthal is crunchy and unfinished — or it can be churned up for proud emphasis. The paintings’ content, the thing that they are about, is not fixed. The paintings sustain prolonged, repeated viewing.

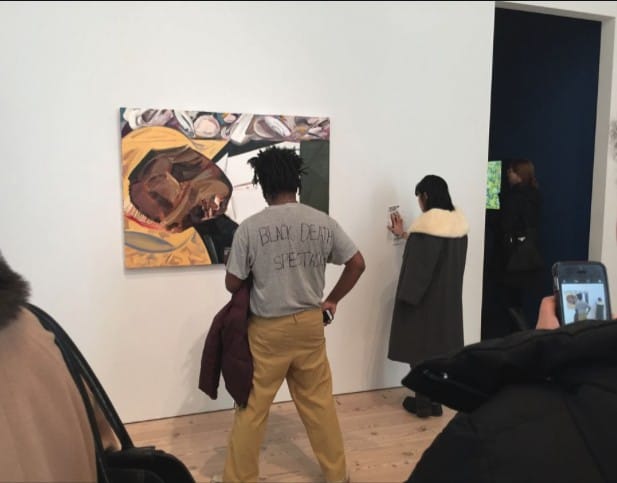

And the paintings stay shocking, every time. You don’t ease into them. You have to work in reverse. Schutz’s 2016 painting of the corpse of Emmett Till, Open Casket, was a locus of shock — an early, at times unsavory chapter in the then-coalescing movement demanding representation, equity and accountability in institutions and society that is at a revolutionary pitch today. That painting became something that you could only ask yourself about afterward. All her paintings do this. And seeing her new work in London today is oddly reassuring, because once the shock subsides, the process reveals itself, and reveals itself to be familiar. Dana Schutz’s steps to wrestle with the world in her paintings are today’s steps. The instantaneous snap of shock upon seeing one of Schutz’s paintings gives way to a searching, exposed methodology of labour, a putting-together, a picking up of the pieces. And the paintings make sense today because this is how we are working through things right now.

During the writing of this piece, the industry behemoth David Zwirner announced to his mailing list, and then on to the trades, that Schutz was joining his gallery. This was a genuine surprise — there’s a lotta loose lips, lotta gossip fiends in the art world — which quickly led to abundant scuttlebutt on gallery Slack channels and at boss-man lunches. There are many big moves happening at the moment, but this was a big one. People are racing to find out the reason why Schutz has joined Zwirner, why she really made this move. I, blessedly, don’t need to think about it. Schutz gives enough in her paintings. She’s shown her work. She’s brought us through the process. And when you’ve shared that diligence and passion, and shown you’re going through life too, sometimes you get to just do whatever you want, do it for you, and for it not to be other people’s business. This is very much Virginie Despentes’ message, and Dana Schutz carries this example. She shared these paintings with us. In a time of velocity and change, these paintings capture this moment. May they endure as a record of this moment.

Relevant sources to learn more

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.6 : Dirty Work And Pure Intentions

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.7 : Rising From Slumber: Narcosis, Creation and David Hammons’

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.8 : Palace Intrigue

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.9 : Accepting Alchemy through Bruce Nauman and the global pandemic