Articles and Features

Palace Intrigue

William Pym’s Standards & Practices Vol.8

William Pym

Standards & Practices

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in his last standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

In the art world, throughout the pandemic era, palace intrigue has been the order of the day. Without our preferred mode of keeping busy, partying, we must occupy ourselves with the intricate comings and goings of our industry, situating ourselves emotionally and physically through a period of wild recalibration. In March the pot got stirred straight away by distress buyers, a class of collectors — day traders, really — fishing around galleries and artists’ studios figuring out who needed money and whether they could assist and enrich themselves. These little dramas provided a pulse of low-dose dopamine hits, a few days’ worth of speculative, pretend action that made afternoons move more quickly while the phone really wasn’t ringing. As the spring wore on and largescale gallery layoffs began, art society became noisy with rancour about rich dealers who appeared to be callous in their downsizing, legitimate sour complaint about sour leadership, alongside angst about worthy galleries who didn’t appear to have the resources to endure. It became clear during this clatter that the stakes of this moment were real. Last week the British dealer Gavin Brown announced in a dual statement that he was partnering with Barbara Gladstone, one of the world’s most venerated dealers, thus ending 26 years of a New York brand that took more risks, gained more fans and did as much for art culture as anyone in the game, big or small. At the end of a spicy spring season in the art business, this was the bombshell.

These shakeups drive the modern art-world story, a 60-year tale that rivals A Dance to the Music of Time in its endless glamorous eddies — it’s why we speculate about them so much. Amid the power struggles and the collapses and the alliances, however, amid all the soap opera of change in an industry that brazenly writes its own rules, comes a reckoning with the self. Brown’s closure of his namesake gallery puts its innovations squarely in the past, part of movements and moments that can no longer be altered, only observed, and these moments force us to parcel our memories. Brown’s Passerby space and its flashing Piotr Uklanski dancefloor, down the block from a lumber yard on blank 15th Street, started slowly fading in meaning from the moment it closed in 2007. I spent an afternoon at Passerby on assignment for Artforum getting drunk alone while the guy wiping down the bar phoned around for someone to fix a projector so I could watch future Turner Prize-winner Mark Leckey’s animation about two drunken bakers called Drunken Bakers, which never happened. This experience has been front of mind for 14 years, I’ve a peculiarly clear picture of it, still, but it is not current events. There’s no way to use this memory, although I’ve long wished to, without it serving nostalgia or myth. As we churn forward, we are reminded that renewal erases as it refreshes. We deify the future, its power, and we try to keep up. The art world looks forward, because that’s where the action is. Action, not reminiscence, is the agent of change.

Watch: Mark Leckey, Drunken Bakers.

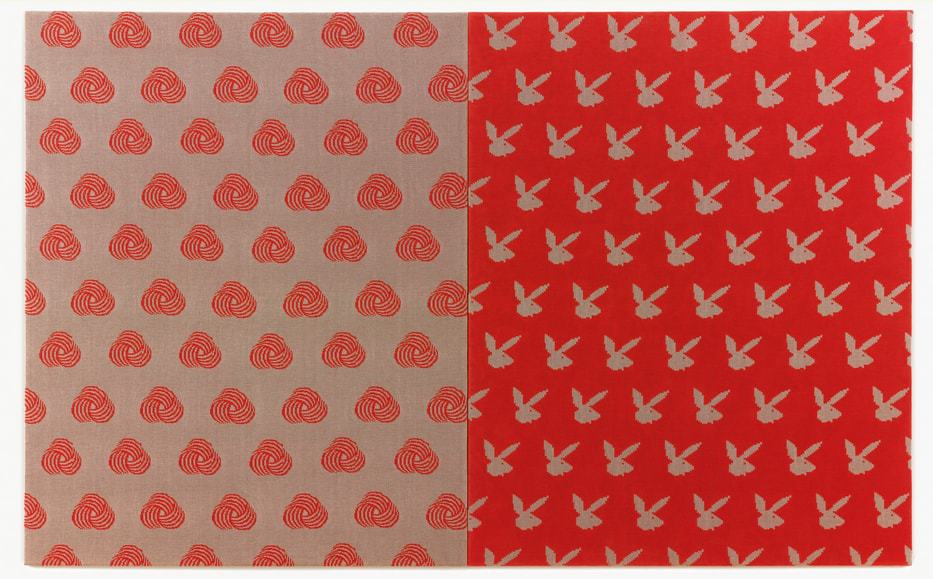

Rosemarie Trockel came of age in Germany through the 1970s and 1980s, where artist tribes of young German men had a voice, a freedom and a public. The Junge Wilde of the 1980s, with Fassbinder their god and Kippenberger their apostle, had power to express themselves — to stretch out and sound off, to take risks and suffer no great consequences. Their art, loud art, had a global impact. Kippenberger’s 1983 painting Sympatische Kommunistin / Likeable Communist Woman is an icon of what would come to be known as problematic art, at once trivial, sexist, insensitive, poorly made and seemingly perfect. 1990s painting students in the USA studied German paintings of the 1980s for their bravery and their volume. And while Rosemarie Trockel existed among those artists, she did not use her voice in the same way.

“While the wild boys barked at the moon, Trockel directed her efforts inward. To look in, and in again, in hopes of reaching the heart of an idea.”

Initiated in 1984, Trockel’s Strickbilder (‘knitted pictures’) carry the heft of paintings without any of painting’s hallmarks. Made of wool, the works are generated from blueprints by computerized machinery. They can look like textiles, rugs, geometric abstraction or minimalist painting. They have no hand, mechanising the perceived warmth of craft. They neuter the traditionally gendered role of the applied arts as women’s work, removing the romantic, denying it that diminishment. Through ease, a performance of ease, they hector the self-inflicted struggle of the German male painters of the period, who bled for results and validation through the physicality of their efforts. They speak, without alarm or zeal, to the muscle of commodity and might of Capitalism: ‘Made in West Germany’, one might see patterned across a work, performing big-issue geopolitics and a basic statement of fact at the same time. On a wall, in terms of presence and seriousness, they equal or best any power painting of the 20th century. They feel no different.

In a career varied beyond the point of containment here, and for which the Strickbilder are merely an introduction, Trockel has used her artworks to ask herself questions, with no deadline or expectation of what answers they will provide, or when. The Strickbilder rest easy on the eyes, but they’re built to welcome the viewer’s deepest interrogations, and leave them with more questions to ask. The most polished nut I can offer about German Postmodernist art is to consider it as a religion in search of its founding text: it is categorically radical art, because it springs from no single history. There are no edicts or traditions to guide the viewing of artworks like Trockel’s, only peculiar emotional connection from which we may work back, figuring out the reasons it makes us feel the way it does. While the wild boys barked at the moon, Trockel directed her efforts inward. To look in, and in again, in hopes of reaching the heart of an idea.

I thought for some time about the dominoes that will tumble after Brown’s closure, the artists and workers whose lives have transformed overnight, the voids in energy, the way style will evolve in ways that will have nothing to do with Brown’s legacy. I thought most of all about how our collective charge through change sweeps up everyone, flattens everything. The rollercoaster of behind-the-scenes action forms the biggest story here, because it has the most people talking about it. The bold-type headlines of palace intrigue have enough fans, enough scribes already, however, while those looking to preserve the finest grain of our story are in short supply. Rosemarie Trockel has long confronted the complexity of modern life by rendering discovery as a process of burrowing rather than explosion, something internal rather than external. I suppose I’m advocating here for an art world that is stable rather than chaotic. I recognize that this is of course an unreasonable ask while the world is on fire, but I am comfortable asserting that we all need to go back to looking at art, obsessing over its details, experiencing it together, saving its moment so important details aren’t forgotten or lost. Rosemarie Trockel shows at Gladstone, it turns out; you could start there.

Relevant sources to learn more

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.4 : Amalia Ulman

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.5 : Notes From The End of An Art Market

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.6 : Dirty Work And Pure Intentions

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.7 Rising From Slumber: Narcosis, Creation and David Hammons’ Basketball Drawings

Gavin Brown Website