Articles and Features

Yours For the Taking: Justine Kurland’s Continuing Story of Freedom in America

Courtesy of Higher Pictures Generation

William Pym, Standards & Practices, Volume 15

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in a recent standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

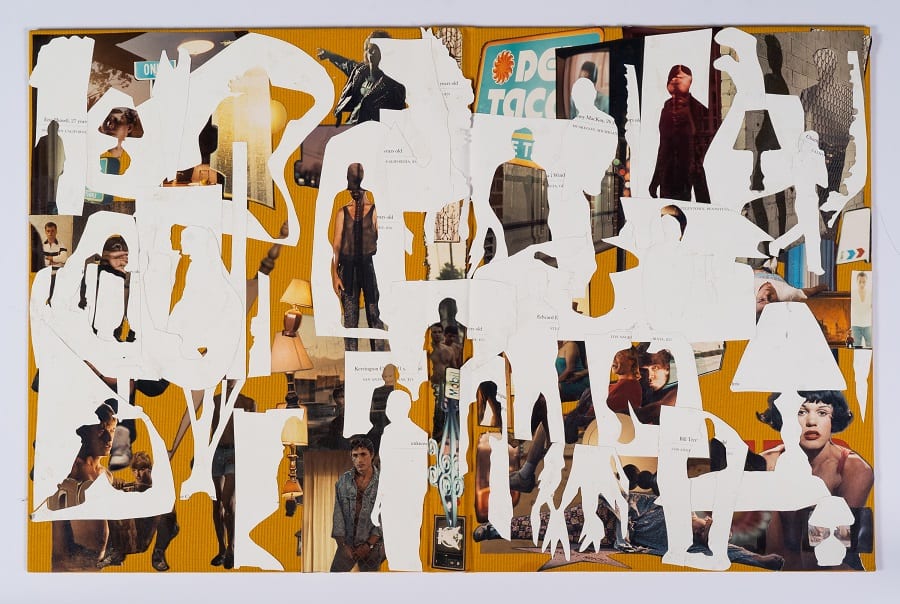

American photographer Justine Kurland just finished a spring exhibition at Higher Pictures Generation, a ground-floor gallery by the sparkly waterfront and sparkly real estate of Brooklyn’s Dumbo neighborhood. The show was an installation of dozens of collages made from Kurland’s library of photobooks, each individually torn apart and then collaged back on to their gutted, butterflied covers. The works covered the walls. Dense, messy. No frames. The books are all by white men, as made explicit in the exhibition title, SCUMB Manifesto. SCUMB stands for the Society for Cutting up Men’s Books, in a tribute and riff on the feminist-anarchist Valerie Solanas’ 1967 SCUM Manifesto. Justine Kurland, for more than twenty years a very well-known photographer, is not known for this type of work at all.

Kurland was part of an emergent movement of photographers at the turn of the millennium who shared tendencies toward portraiture, naturalism, womanhood, and nature. This moment crystallized in the 1999 group show Another Girl, Another Planet at Lawrence Rubin Greenberg Van Doren Fine Art in New York, an exhibition that felt seminal even as it was happening and has only improved with time. Kurland has finished her MFA the summer before and was just starting to show an ongoing series, initiated in grad school, of adolescent girls in nature. These photographs, now known as the Girl Pictures, became very popular very quickly, and for good reason, because they did several things well. They felt close to documentary, hands-off in terms of style and scenography, not theatrical or arch. They felt honest, because they were faithful to their subjects and provided growing girls with a safe space to be themselves. And they felt lush, alive, naturally lit and humming with landscape. Even in a cement ditch under a highway overpass, Kurland’s girls could summon a utopian, pastoral tradition threading back through art history for a thousand years. The Girl Pictures carried a message of freedom at every level, from the romantic hope and wanderlust baked into the American terrain to the fact, the miracle, that the girls in the photographs could do whatever they want and be whoever they wanted.

Kurland was established early on, and from there she was able to simply keep going. She worked on the road for many years, finding America in the people who explored it and established a place to settle, or a way to roam. Her subjects in this period included mechanics, earth mothers, communes, hobos, and nature, always. Kurland has continued to move and work in the flow of other searchers and individualists, and her eye is her own, her photographs unmistakeable. Hence the surprise of SCUMB Manifesto, which is not recognizable as Justine Kurland. The works are turned inward and intimate in scale, rather than expansive and out there. Basically, it’s difficult to picture Justine Kurland indoors.

Unexpected though they are, the content and the intent of the SCUMB Manifesto works are straight up, just like the exhibition title. Each collage is a one-to-one encounter with a white man artist through their monograph, and she treats each encounter on its own terms.

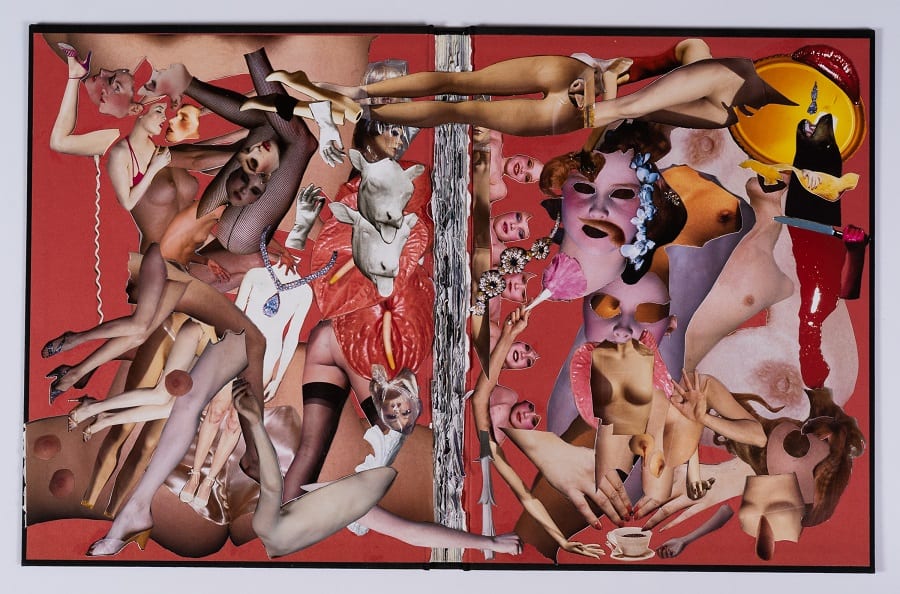

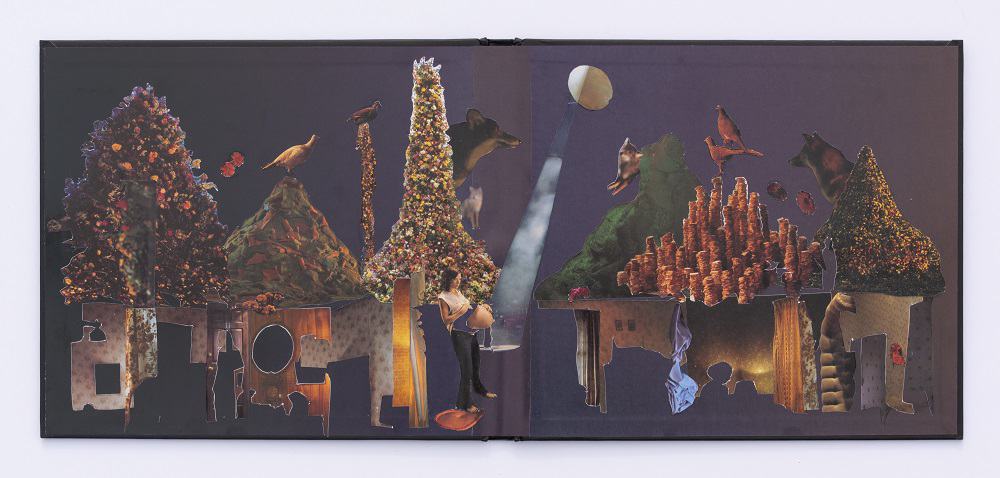

Courtesy of Higher Pictures Generation

Some of the collages effortlessly knock their subject off his perch: the parade of bent legs and bright red everything, compressed together from Guy Bourdin’s Exhibit A, makes the French kinkmaster seem exhausting and a little obsessed. Some of the collages are unserious, or low stakes: Lee Friedlander’s late-period America by Car becomes an agreeable Orphic whorl of fragments of steering wheels, little more. Some of the collages suggest inside jokes or mild shit between people who’ve known each other a long time: Kurland’s collage of Twilight by Gregory Crewdson maintains the basic premise of classic Crewdson spooky suburban sci-fi, then renders it kitsch and fantastical, taking out all the male Hollywood gravity from the work of her onetime teacher. Some of the collages suggest a degree of conscious commentary: in the waterfall of junkie limbs collaged from Larry Clark’s Tulsa, a pistol appears three times. In Kurland’s telling, the gun reveals itself as the most threatening thing in Tulsa, the real killer as black metal in a sea of soft, fallible flesh.

Courtesy of Higher Pictures Generation

The SCUMB Manifesto works are profane by the very nature of their existence, but they never eviscerate, they never truly destroy. Some, demonstrably, are kind goodbyes. Cancellation is not the point here. Kurland’s conceptual gesture — to remove the imagery of men from her life, and to reset the way personal art history forms— is a ritual of self-care as much as anything else. It’s about her. She removes these books from her life in order to see and live differently. This may sound like pandemic behaviour, but Kurland began the SCUMB works in 2019. Kurland’s edge has been building for a while.

There is glee in Kurland’s cutting up of these artefacts of photo history, and no ugly flipside of grievance. The work isn’t war. It is softer than its revolutionary title suggests, matter-of-fact in its desire to get these men out of her way so she can move forward. “The first condition of freedom is the ability to move at will,” Kurland explained to Aperture last year. She has torn photobooks from their spines because she doesn’t want anything to block her freedom. Freedom is having nothing keep you from enlightenment and progress. The SCUMB Manifesto works have everything to do with the photographs she’s been making since the late ’90s, it turns out. They are about clearing a path.

Relevant sources to learn more

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.9 : Accepting Alchemy through Bruce Nauman and the global pandemic

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.10 : Working Through A Daze With Dana Schutz

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.11 : Halfway To The Future. Saatchi Yates’ Proposal For Tomorrow’s Art Gallery

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.12 : The Body Won’t Quit. Finding a Way Through 2021

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.13 :Thomas Hirschhorn and Our Life in Ruins

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.14 : A Mellowing Dictator. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Jonathan Meese