Articles & Features

From Antiquity to Modernity, How Art Fairs Became A Cultural Mainstay

By Naomi Martin

With almost 300 occurrences around the world in 2019, the art fair is undoubtedly one of the most crucial infrastructures of the global art market – an essential platform for business, trade, networking, and a considerable industry on its own. But how did art fairs initially come to be? What have been their most essential features throughout history, and how much of their original inner structure has the contemporary art fair retained, despite its many transformations? Here we reconstruct the evolution of the art fair, observe how societal change and historical progress have fostered new formats and features, enabling the omnipresence of the art fair as we know it today.

The Origins of Art Fairs

Religious Festivals and Pilgrimages

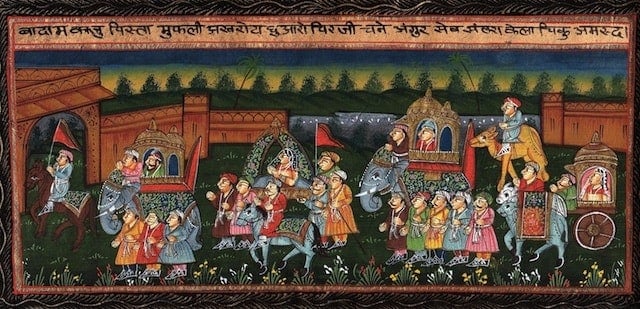

Religious festivals in Antiquity are considered to be the precursors of art fairs, as they initiated the structural qualities that would become quintessential for all future events of such magnitude. These annual gatherings and pilgrimages, intertwining religion with commerce, were dominant in all great ancient empires, from the Roman and Greek Empires to the Han-Dynasty. They endeavoured to showcase the outstanding and inimitable merits of the elite, by means of demonstrations, spectacles and displays of rare items, that would bring together the upper echelons of the Imperial populations.. Remarkable efforts were invested in the organisation of the festivals, to highlight their exceptional character and to attract as many people as possible.

Such festivities would put on hold the daily activities and gather masses in one single location, thus requiring sophisticated, especially apropos transportation, food and shelter. The promotion of these events in Antiquity also introduced the earliest forms of networking, as the organisers and merchants would exert themselves to spread the news throughout an entire empire. Metamorphosed into worlds unto themselves with a distinctive framework and inherent rules, these events encouraged participants to strengthen existing ties and establish new ones.

As people from distant lands would gather for the sole purpose of these festive events, they would bring along the rarest and most valuable objects, which would be proudly exhibited to spark interest, curiosity and appeal among the visitors. These artifacts were displayed in temporary edifices – houses, temples or tents – especially erected for the occasion. This tradition slowly became an essential aspect of the festivals, and eventually led to an increase in trade and the creation of markets, which resulted in the familiar association of fairs and commerce.

Artisanal Fairs

Artisanal fairs hence emerged as an unintended outcome of these religious festivals and gatherings, and were especially popular in the Roman Empire, up to the late 5th century. From there on, societal changes affected organised commerce which significantly weakened and nearly vanished, until the late 7th century when it resurfaced with the Saint-Denis fair established near Paris, which paved the way for the further developments of artisanal fairs. This model swiftly blossomed throughout Europe, and particularly thrived around the 12th and 14th centuries, most notably with the Champagne fairs of northeastern France, and the Stourbridge fairs in Cambridge, England.

The 12th century Great Fairs of Champagne were a milestone in the history of such events, mainly because of the creation of the “conduct of fairs”, and the “ward of fairs”, namely a protective system for the merchants, and an elite of guards ensuring security and the upright fulfilment of all contracts. Due to their locations, these fairs were also frequented by merchants from all across the globe, which induced the need to consolidate an international system of financial credit. This facet became essential, as it consolidated trade relationships outside of the events, and introduced the sales-partner model as well as the patron-client relationship, two key features of premodern economics.

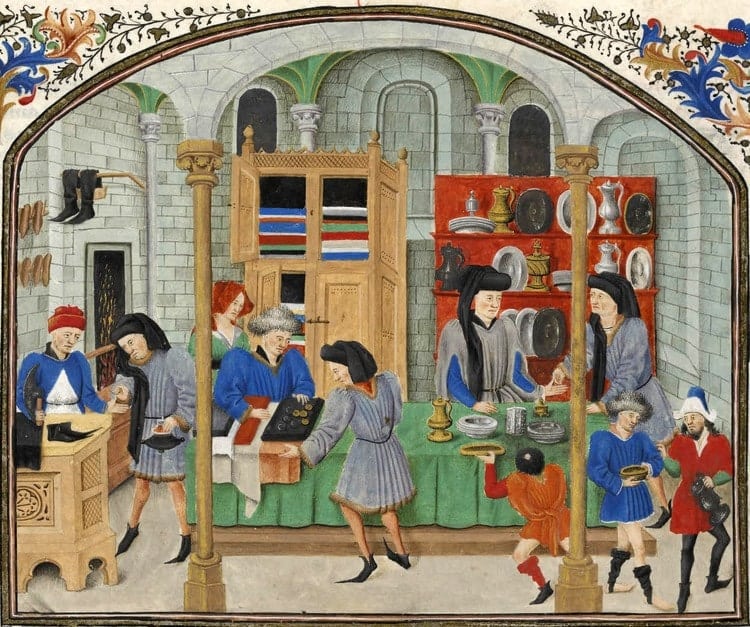

Artisanal fairs also flourished throughout the 15th and 16th Centuries and progressively drifted away from religion and sacred associations. They evolved into actual platforms for trade where the emphasis was put on the rarity of items displayed and the formation of enduring marketing relationships, usually to take place at a recurring point in the calendar. While they essentially retained the initial architectural configuration of religious festivals, they reshaped their inner structures, abandoning the idea of an event fostering a political and spiritual message, and instead focussing on mercantile activities. The aesthetic appeal also became a focal point, with merchants relentlessly working on making their stalls as attractive as possible. The modes of display began to take precedence, with eye catching presentations increasingly the norm.

The Earliest Instances of Art Marketing

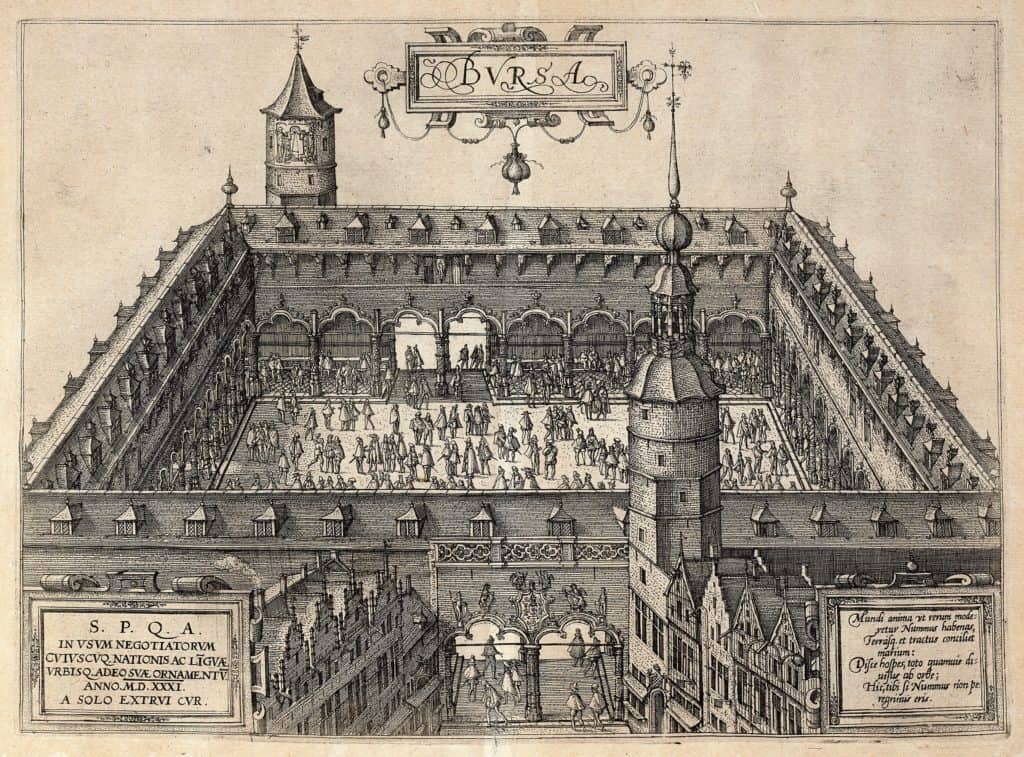

In the 16th Century, the city of Antwerp became an international hub for trade and fairs, with an exceptional number of foreign merchants settling in the city and exporting globally from this base. Artists and other artisanal professionals thus discovered a thriving audience and rich expanding markets where they could prosperously sell their work. On the basis of biannual fairs, Antwerp’s expanding economy secured the city’s reputation as the reigning commercial and financial capital of Europe. The first ever fair to be specifically designed for the display and sale of art opened in 1460, in the courtyard of the Church of Our Lady, which would later become the Cathedral of Antwerp. Known as Our Lady’s Pand, the fair exhibited and sold paintings, sculptures and illustrations, as well as some manuscripts. The event encountered tremendous success, and thus became a new model for the marketing of art.

Prior to the 16th Century, the buyer-seller relationship was a rather direct one, the merchants owned the goods and the buyers would buy for themselves. But the new commercial infrastructure and magnitude of the Antwerp art fairs brought about a new kind of infrastructure, the art dealer. With their large network, educated background, endless capital and a commercial mindset, the dealers would not only link seller and buyers, but also facilitate sales thanks to funding. The role of the art dealer became indispensable, and has been in constant expansion ever since.

With the technical advances of the 17th and 18th Centuries, interest grew towards industrial production and machinery, which led to the rise of sample fairs, slowly replacing artisanal fairs. These sample fairs were not purposely designed to sell merchandise, but rather meant to advertise new items and promote their production, fostering the trade fair premise of engendering future orders and not just on-the-spot transactions. . Although these exhibitions were of a more industrialized nature, they also displayed artworks from around the globe. As the French Salon model and other similar forms of art exhibitions in other countries were gaining in cultural significance, the presence of art in the sample fairs began to dwindle as it became increasingly concentrated in more specialised forum.

The Rise of the Exhibition Model

Le Salon Parisien

In Paris, between 1667 and 1789, the monarchical regime was funding exhibitions exclusively displaying art by the members of the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture. These shows were initially semi-public, only opened to a certain elite, but the restrictions loosened around 1725, at which point they took the name of Salons – after the Salon Carré du Louvre, where they were held. When the Académie Royale was supplanted by the École des Beaux-Arts in 1795, the salons began to welcome all artists, regardless of their affiliation to a certain école.

Over the years, the selection process remained nonetheless controversial and tainted with a political agenda; the 1863 edition was exclusively reflective of the the Emperor’s traditional taste in art, and his appreciation for historical depictions – he purchased for his personal collection Alexandre Cabanel’s The Birth of Venus immediately after seeing it. This led more progressive artists to contest the system, the ones whose works had been repeatedly rejected by the jury decided to challenge the institution, and were granted by Napoleon III the opportunity to exhibit their works in another salon, resulting in the creation of the first Salon des Refusés, which displayed works from Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, and Édouard Manet, among many others.

The Royal Academy of Arts & The British Institution

Across the English Channel, the exhibition format was also favoured and in demand. In 1768 London, architect Sir William Chambers presented King George III with a plea signed by approximately 36 artists, demanding the institution of a society to promote the arts of design, as well as suggesting the creation of a School of Design, and the institution of an annual exhibition. Enthralled by the idea of a large scale exhibition, the King gave his approval, hence leading to the creation of the Royal Academy of Arts. Since 1769, the Summer Exhibition of the RA has been held every year without fail, making it the largest continuously staged open submission art show.

In contrast to the Royal Academy of Arts’ Summer Exhibition and its open submission structure, the British Institution for Promoting the Fine Arts in the United Kingdom was formed as a slightly more conservative private gallery and fostered regular exhibitions of Old Masters paintings, while also operating as a school for artists, who had the opportunity to reproduce classical paintings lent by its members. Concerned with stature and rather conservative in taste, it was mainly admitting distinguished visitors and noble subscribers, which ended up damaging its relationship with younger British artists, who were looking for change. While it thrived for almost sixty years, it was disbanded in 1867, at which point the Royal Academy of Arts took over the loan exhibitions of Old Masters paintings.

Great Exhibitions

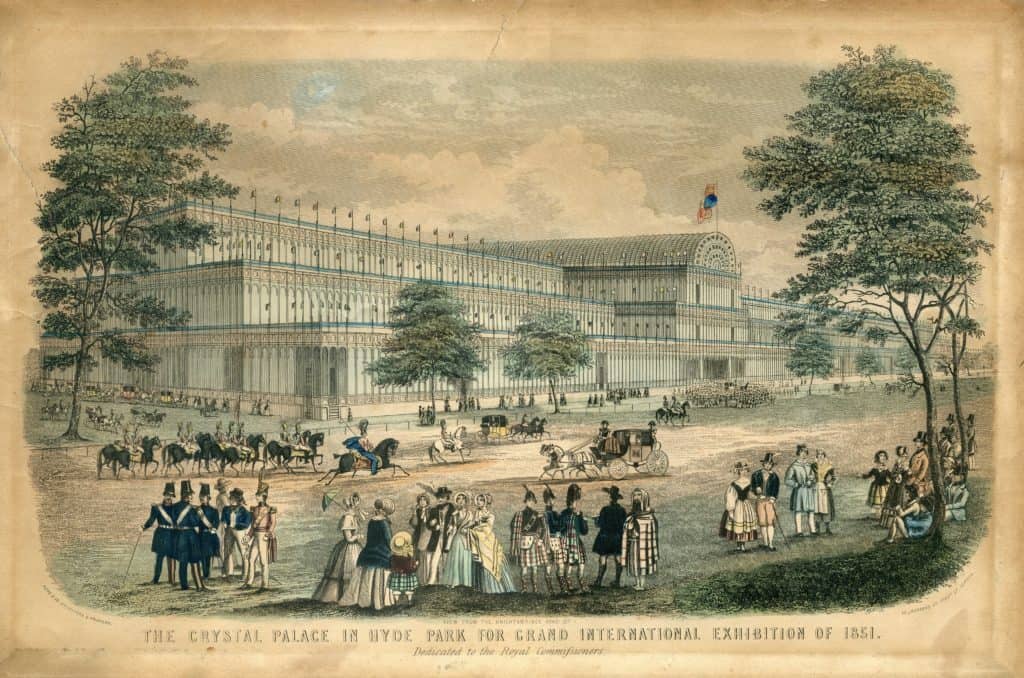

“Yesterday I went for the second time to the Crystal Palace, it is a wonderful place – vast, strange, new and impossible to describe, as if only magic could have gathered this mass of wealth from the ends of the earth.”

Charlotte Brontë

The long-lived institution of religious and industrial fairs, combined with the global success of the exhibition format, eventually led to the establishment of the notorious World’s fairs. The idea emerged in London, stemming from Prince Albert’s desire to promote the success of British Industry, and showcase the magnitude of its colonial empire. In 1851, the very first international exposition was thus held in Hyde Park, within the iconic greenhouse-like Crystal Palace, designed by Joseph Paxton. Scientific and industrial demonstrations from around the world were displayed, as well as distinctive artifacts and marvellous treasures which would provoke tremendous excitement among the general public. Around six million people attended the Great Exhibition of 1851, which encountered an astonishing financial success – its structure ultimately became a vehicle of choice for exhibiting and influencing culture around the globe.

Although the Great Exposition’s hybrid aesthetic was more often inclined to promote industry, new technologies or even curiosity cabinets, it still allowed the inclusion of art, which was particularly represented in the Exposition Universelle of 1900. Towards the end of the 19th century, Paris had become the epitome of world’s fairs, and its 1900 edition is still regarded today as the most illustrious. Not only were some of the most iconic Parisian landmarks erected for the occasion – Pont Alexandre III, Musée d’Orsay, Petit Palais and Grand Palais – the Expo of 1900 put a distinctive emphasis on exhibiting paintings and sculptures, and truly brought international attention to Art Nouveau.

The style was represented most notably with Hector Guimard’s Metropolitain stations, René Binet’s Porte Monumentale which was the entrance of the fair, Victor Horta’s furniture, as well as an exhibition displaying works from artists of the German Jugendstil. In the Petit Palais, French art was exhibited with works from Renoir, Courbet, Monet, Rodin and Cézanne, among others; while in the Grand Palais, the greatest collection of contemporary art ever assembled at that point was displayed, with works from international artists such as Klimt and Picasso – who visited Paris for the very first time to see his painting exhibited in the Spanish pavilion.

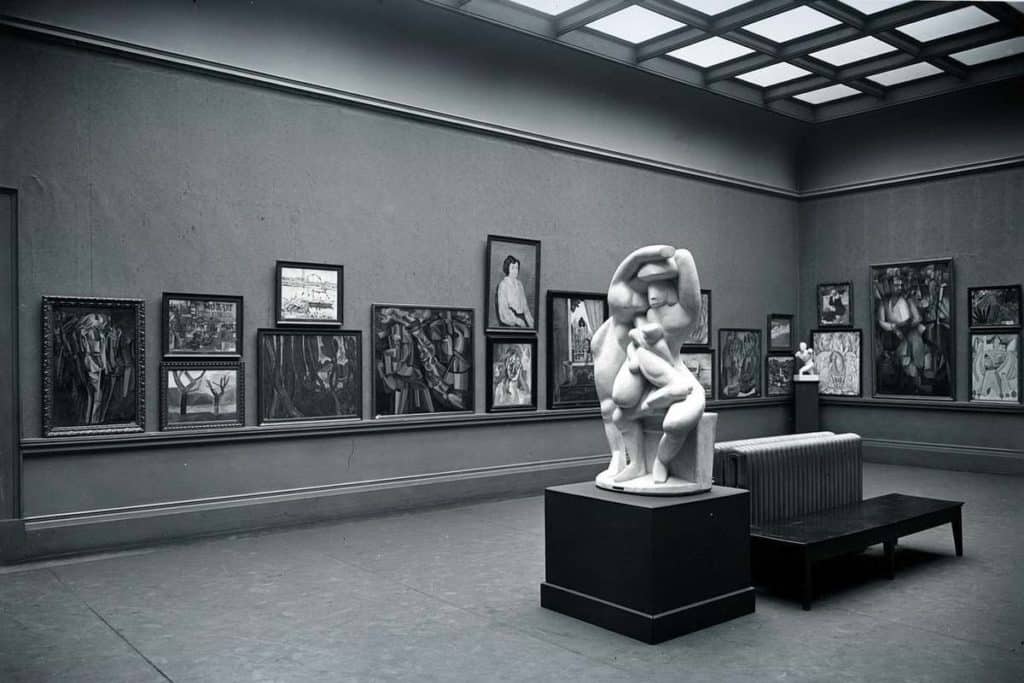

The 1913 Armory Show

While interest in World’s fairs gradually declined, the art market’s expansion was on the rise. The exhibition endured as the format of choice, and no other event in the 20th century had the impact of the 1913 New York City Armory Show, which is considered to be the greatest and most spectacular exhibition ever held in the United States. The Armory Show was captivating and provocative for its time, perceived by the American media as a display of thought-provoking ideals, endorsing madness and mayhem. President at the time, Theodore Roosevelt openly affirmed when asked about the exhibition: “This is not art”. Over the course of a month, it displayed over a thousand artworks from almost 300 artists – both Americans and Europeans – including Pablo Picasso, Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Marcel Duchamp and Edward Hopper, to name a few.

What made the Armory Show such a turning point in the history of art and exhibitions, is that it introduced the American public to the European avant-garde. It is almost impossible to fathom the impact that the Armory Show has had on America’s understanding of modern art. Nowadays, technical advances have made it possible for us to appreciate art produced on the other side of the globe, but in the early 20th century, only a handful of Americans could visit Europe and witness the magnitude of the artistic avant-garde revolution. Exhibiting works by these radical Europeans artists in New York City was truly revolutionary and mind-blowing at the time, and regardless of critiques, the success was immeasurable and set the tone for the evolution of exhibitions and of the modern art market in the U.S.

The Rise of Contemporary Art Fairs

Growth & Expansion

Throughout the 20th century, major cities such as Paris, London or New York were already established as major artistic hubs, with a high concentration of galleries and dealers, as well as a thriving market. Smaller cities in other European countries did not have the impact of such a high-density network, although they did have numerous collectors and the basis for building a strong market. Contemporary art fairs hence did not emerge in capitals, but rather in the periphery of the art market, in cities which were looking to develop and bring visibility to their market. The first of its kind is considered to be Art Market Cologne – later renamed Art Cologne – established in 1967, followed closely by Art Basel in 1970.

The earliest structural efforts in Art Cologne were modelled after the Stuttgart Antique Book fairs, resembling the artisanal fairs of the past centuries, and a similar format was adopted by Art Basel. In the early stages, the fairs were regional events, but the participating dealers rapidly expressed their desire to expand to an international network. These art fairs were facilitating business activities in the art market and helping galleries secure their presence and network, but they were at first professional trades, reserved for dealers. The 1990s crash of the art market led to a restructuring and to the creation of new networks, which induced the formation and proliferation of many types of fairs, often with an emphasis put on locality. Art Basel Miami 2002 is considered to be the turning point of art fairs in the 21st century, where the phenomenon truly took off – in the following years the number and locations of art fairs exploded.

The incessant growth of the art market transformed the fair’s infrastructure, which eventually brought about new commercial features such as the implementation of VIP rooms, or the necessity to entertain wealthier clients. The cost for galleries thus skyrocketed, and created a multi-tier system for the haves and the have nots of the gallery world. Multiple fairs ran concurrently, all reflecting differing levels of the gallery hierarchy, but collectively housing many hundred of galleries at one time. The current model has been highly criticised over the last few years, as many gallerists and dealers deem the fair victim of its own success, accusing it of benefiting the giants while neglecting the smaller players – often required to pay the same fees while selling considerably less expensive works – while smaller galleries and emerging artists can be overlooked in the selections. Many are wondering if the art fair has become too commercial a structure, the proliferation engendering fatigue among the buyers and enticing mixed feelings among artists who, whilst needing the exposure, are ambivalent about the manner their works are displayed.

“An artist entering an art fair is like a teenager barging into his parent’s bedroom while they’re having sex.”

John Baldessari

Virtual Editions

The art fair calendar is looking rather different in 2020 – the current pandemic has constrained many fairs causing them to cancel or reschedule their events, but many have opted for supplemental online editions. Online viewing rooms and exhibitions are not a new thing, the infrastructure was already in place to enhance physical fairs, but it is safe to say their influence has certainly magnified in these times of social distancing. Art Basel Hong Kong was the first to move to digital settings in 2020, its qualified success consolidated the hope that the art market could move forward and overcome the crisis, whilst prompting other fairs to move online with increasingly ambitious technological offerings. While these wired events might be lacking human experience and the genuine appreciation of art in real art provides, they still engender a number of benefits, such as more price transparency, or even phasing out the “intimidation” aspect some art lovers might have formerly experienced in person.

The future of art fairs might seem unclear under the current circumstances, but it is still solid. Some have already rescheduled physical events later in the year, while others are looking to innovate even further, such as Untitled, Art and the first ever virtual reality fair, coming this summer. Chances are things will never go back to the way they were – a new normal is arising in each and every aspect of our lives, including the art market, but this brief history of art fairs has proven that for hundreds of years, the structure has endured and evolved, with no convincing reason why this shouldn’t continue.

Relevant Sources to Learn More

Artnet’s 2020 art fairs calendar

Discover the entirety of the artworks exhibited at the 1913 Armory show

Read about The Changing Face Of The Exhibition Format

Read about the difference between the primary vs the art market

Art Market Q&A – Your questions, answered