Articles & Features

How and Why To Buy Video Art: The Insiders Guide To Collecting

Generally speaking video art has long been considered an outlier amongst collectors and their most common acquisition habits, supposedly the preserve of esoteric Institutions and their curatorial professionals. Its alleged challenges are numerous and well-documented, yet tired arguments rehashing the notion that collecting video art requires a particular kind of courage, often developed from a rarefied knowledge or taste, continue to prevail.

But why should this be the case? After all, screens are both everywhere we look and immediately to hand, often providing the closest link with the significant people and events of all our lives. From phones and tablets, to computers and televisions, all the way to electronic billboards and jumbotron displays in stadia, airports and public spaces, the moving image unfolding in real time is by far the most ubiquitous communication mode of our age. In this context and with these inarguable qualifications, why is video art not the most consumed form of contemporary art amongst both afficionados and amateurs alike, given its status as the most apposite medium to offer an insightful reflection of today’s society and all its facets?

As we approach the launch of Barcelona-based LOOP Art Fair’s 2020 online edition, we at Artland sought to get to grips with the ideas, challenges, and, in some cases, prevailing myths surrounding the collecting of video art. The fact remains that video works constitute around only 10% of the world’s privately held art collections, with paintings consisting of the overwhelming majority; at least 80% at recent reckonings. To understand the intricacies of the medium and what it means to acquire, own and cherish such things, we decided to assemble a brains trust of experienced collectors specialised in video art, looking to ascertain how and why one goes about collecting what should be long established as the dominant medium of our age.

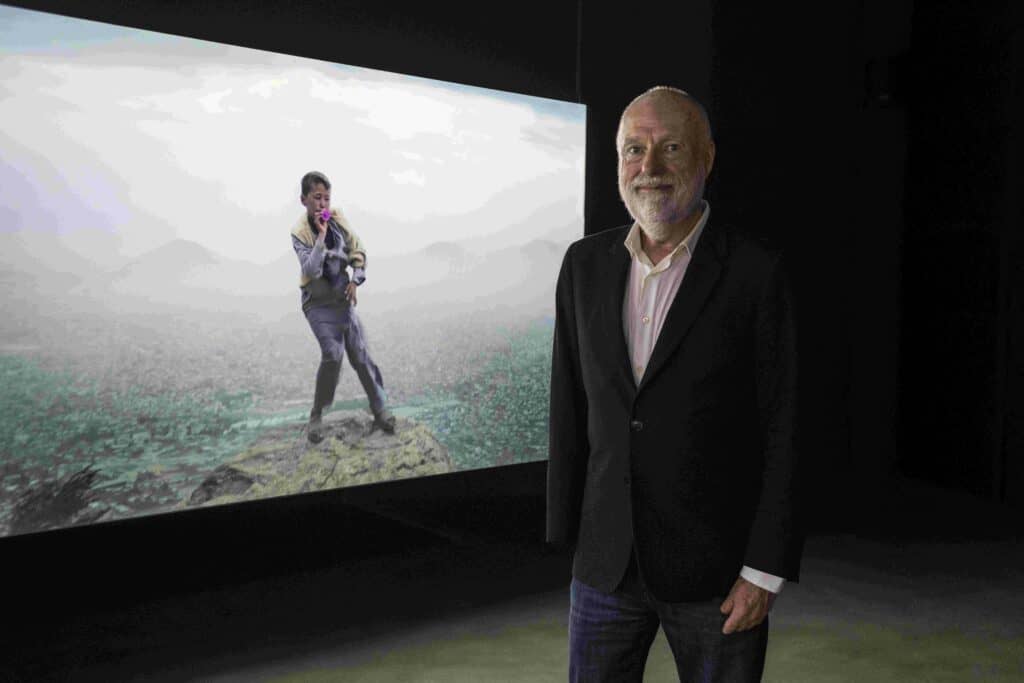

We talked to Han Nefkens and Alain Servais, both of whom are renowned collectors with a long-standing, industry wide reputation for the collecting of video art. To learn more about their respective experiences a short bio of each is at the foot of this article. With a combined experience in the field in excess of more than 40 years, we put to them an array of formulaic questions that summarise the received and hackneyed ‘wisdom’ about video art collecting—seeking to elicit their insights primarily in expectation of learning more, but also in hopes of debunking some of the tired tropes of thinking that continue to endure.

So what are the common arguments that might inhibit the acquisition of video works by today’s art buyers? Our questions are reflective of general attitudes towards the medium, and were compiled to see if there was a consensus at the heart of their respective approaches. Questions like; did you collect more traditional art media before you collected video works? And did you feel that you needed a more practiced or experienced ‘eye’ before you felt ready to collect video work? Are there characteristics of video work you particularly look for—a filmic narrative, particular visual effects or qualities? Do you want or expect it to elicit the same feelings as you might want from a painting or sculpture? As a collector, how is ownership of video defined or characterised for you? Does it feel different to the ownership of more object based artworks? Do you live with video works in your home environment? Are there any video works that you have been prepared to overcome significant logistical, installation or maintenance challenges in order to acquire?

Their responses were of course somewhat varied but consistent in many key regards—both shared a dedication that can only be engendered by true passion, and redolent of the conviction and commitment one finds behind the impetus to collect ardently in any field. Their answers were also striking in their humility—both are accomplished, successful and affluent individuals, yet modest enough to be suffused with curiosity about the ideas of others, actively seeking them out and absorbing them eagerly in order to inform and supplement their own.

Whilst video works unfold in a filmic way in real time, there are of course enormous variances in approach. Nefkens spoke compellingly of his experience of the first video work he acquired, Remake of the Weekend by Pipilotti Rist. He was captivated and deeply moved by the sumptuous visual universe created by Rist, and by the way it enveloped his own whilst he experienced her work. The experience he describes, that of being overcome and overtaken by the potency of his apprehension has its roots in the aesthetic philosophy of the Eighteenth Century, when philosophers began to identify the source of these kinds of goose bumps and linked them to the sublime. Nefkens’ feeling, at its very core, is not so different to this. Nor for that matter, is the experience of works of other media that have the power to elicit similar responses. Most art observers, seasoned or otherwise, can relate to powerful evocations arising from, as examples, works by Bierstadt, or Ansel Adams, the humming atmosphere of a Rothko, passages of bravura impasto in certain kinds of paintings, or the breathtakingly weightless compositional assurance and seductive material perfection of a Brancusi. The stimuli vary in the forms they take, but the point remains—potential aesthetic triggers are endless, and are of course intrinsically linked to the individual and their own predilections. Nefkens agrees “It’s almost a psychoanalytical question: why video work? It has something to do with the fact I’m a writer and that somehow I’m always looking for a narrative of life itself. Obviously video work lends itself to a broader narrative than other media”. It is no challenge to find video works that convey narrative, just as it is easy to find video works that echo the aesthetic traditions of romanticism even whilst extending its trajectory. Anyone who has watched Gordon and Parrenos’ Zidane: A Twentieth Century Portrait, Doug Aitken’s Song One, Kjartansson’s The Visitors, or works by Grasso, Charrière, or even Matthew Barney, can attest to video art’s unique ability to encapsulate the widest possible gamut of human experience, often within a single work. But the question of narrative remains an important one. Many video works are open ended, rejecting the linear narrative more commonly associated with its mainstream cousins in cinema, and often looped with no specific beginning or end—a hermetic continuum of highly distilled experience that cajoles the viewer to look beyond the simplicity of mere storytelling.

Alain Servais is renowned for boldness in his collecting – any given installation in The Loft, the former warehouse in Schaerbeek, Brussels, that is home to rotating displays of the Servais Family Collection is noted for a wide and diverse array of artworks, a collection which feels full of objects that loudly proclaim their newness and sometimes executed in materials one never even knew existed. Political and socio-economic themes abound in the works he favours, yet for Servais “I never collected any media specifically. Video always went along with photography, sculpture, installation, digital art, etc. The idea was always more important than the medium and it still is.” The most important answer here, containing an authenticity which one suspects is at the heart of any collector’s vocation, lies in the work’s essential communicativeness; “Like for any work of art, I am looking at the way a work reaches the best balance possible between the visual impact and allowing me levels of awareness I had not reached about our humanity. There is no technical recipe for this but bringing an original twist to a question about our times is more important than any technical tricks.” When accounting for the immense versatility of video work, it must surely be unique among media for the sheer scope of ways in which this can be achieved.

Given the above, it is perhaps no wonder that our two panellists shared a genuine incredulity that the collecting of video art could be regarded as a challenge at all. When asked if his prior collecting experiences enabled him to build up to embracing video, Nefkens retorted that the very first of work art he ever acquired was a video work—”it was really video art that seduced me into the art world to begin with.” Servais also gave the notion short shrift: “I even find this question sad as it seems to refer to a conservatism implied in the initiation of collecting through painting. Painting is the only medium I was and I still am not attracted to. It seems to me very obvious that moving images are the medium recording our times that many will still want to look at in 30 years time, my benchmark for the relevance of a collection”.

What then of the main conundrum at the heart of many collectors’ hesitation? Perhaps it can be found in the non-material quality of video art that might mitigate a sense of ‘ownership’? A principal objective in the minds of many collectors when buying art, despite the fact that many would disingenuously dispute it, is that of acquisition and accumulation; stockpiling luxury commodities that can be displayed, evaluated and traded as precious objects. With video this is arguably a greater challenge, and likely also explains its relatively low percentage of representation amongst galleries, auctions and even institutions. But within this another key point emerges; that the purest motivation of all for collecting art is direct access to the originality and inspiration inherent in the ideas themselves. Compared to this, notions of material acquisition are less than secondary.

Nevertheless, the collecting of video art does not leave the buyer with an item of no material value, however abstracted or insubstantial it might physically be when compared to other media. All of our interviewees were at pains to point out the strides the industry has made in protecting both the rights of the video artist and those who buy or produce their works. Servais explains that “there is legally no difference between owning a painting and a video” but that galleries need to improve in the manner they communicate to would-be video collectors. In his experience, he feels that they have been deficient in explaining clearly the increasingly industry-standard practices of master copies, editions, rights and certification that protect the interests of all the stakeholders. Certainly, a lack of clarity and transparency for either party has been an accusation levelled at video, but things are changing and render this argument obsolete. In open acknowledgement of the issue, and in efforts to support the video sector of the art industry, LOOP fair has itself commissioned a legal protocol from intellectual property lawyer Enric Enrich, and which they have made freely available as an open source download in both English and Spanish on their website.

Video works are also cumbersome and expensive to install and intrusive to live with, so the story goes. Committed video collectors must find ways to accommodate this ‘reality’ if they wish to make video art a vital part of their lives. To this end one might have expected our interviewees to describe their homes as meticulously planned quasi-institutions, configured with walls and monitors of moving images and echoing with the accompanying sounds. Yet, perhaps surprisingly, neither of them live habitually with video works in their home environment, dispelling fanciful images of eccentric domestic interiors replete with complicated and expensive audio visual accoutrements. Han Nefkens describes enjoying video works at home in an informal fashion with visitors, describing gatherings of friends as ideal opportunities to screen them. He spends a lot of time reviewing works anyway in the course of his Foundation’s work, and is often looking at works repeatedly either as part of selection committee work or for determining candidates for awards or support of some kind. Besides, the argument that video art is tough to accommodate is also slightly absurd—why find a problem where none exists? Servais engagingly explains the choices at hand; “Whether they are videos or any other medium, I am not living continuously with art. As art is ideas, it is always ‘noisy’ and therefore I always devise two lightings of the places I am living in: one for regular living and one for enjoying art. If I want to see art I turn on some lights. If not I leave it in the dark and it disappears. I do the same with video.”

In this covid-era of truncated travel and transit, and where institutions have their budgets decimated by a devastating lack of footfall, video works also provide innumerable practical solutions—they can be transmitted easily with no logistical challenge or exorbitant cost, barely even requiring insurance in the conventional sense. Admittedly, though access to advisers, curatorial scouts and the infrastructure of personal foundations is beyond the average collector, fruitful opportunities do exist to investigate this under appreciated medium. This is the territory occupied by LOOP Art Fair, a specialist forum for both the seasoned and uninitiated to explore and discover. Created in 2003 by dedicated experts and rigorously tailored to encompass and summarise global trends in video art production it is the ideal resource to learn that video art truly does encapsulate an ideal collecting position for today. Our collectors agree since all have found it it to be a valuable and rich source of discovery as an adjunct to their usual collecting activities. In spite of his considerable network and experience Mr. Nefkens has been delighted by numerous discoveries at LOOP, “I’ve always gone I bought several works there.” On one occasion whilst encountering a work that spoke vividly to him, he determined on the spot that he wanted to offer that artist, based in Africa, a residency in Barcelona, “We talked to the gallery owner and she called him on the phone while we were right there“. On the subject of the fair’s cohesion, Mr. Servais concurs; “the founders of Loop, which I believe I have not missed since its origin in 2003, have managed to create the right atmosphere to go through a carefully selected list of tens of quality videos. They are the only ones to have managed this feat. They also often gather the best specialists of the medium to discuss its challenges and evolutions.” So there you have it, from the many screens of LOOP and its participating artists directly to yours, pay this year’s online fair a visit and take the time to give video work a chance—if one determines to look, and then decides to try and actively see, the rewards are considerable. The reasons not to have dwindled to nothing.

- Han Nefkens: Since 2016 the Han Nefkens Foundation has focused exclusively on its eponymous founder’s first collecting love, video art, supporting international video artists through awards, scholarships, production grants, and various other forms of mentorship. Through the efforts of Nefkens, a dedicated internal team, and even a global network of scouts, they continually source and unearth new talent, not only facilitating the production of works through a collaborative process, but also enabling exhibition opportunities through the of finding platforms, institutions and residencies to work closely with in their dissemination. The first video work he collected was Remake of The Weekend by Pipilotti Rist in 1999.

- Alain Servais: Brussels based collector Alain Servais has long been an insightful commentator regarding emergent trends in both art practice and the art industry and ecosystem that sustains it. Renowned for his strident opinions on Twitter and on many panels and symposia over the years, he famously eschews painting and conventional art in favour of video and other new media works, often regarded as raw, experimental or unsettling in some way. A 900sqm converted factory premises in the diverse Brussels neighbourhood of Schaerbeek is among his former residences, and, now known as The Loft, has played host to a rotating display of his collection, often guest-curated and according to prevailing socio-political and economic themes. The first video work he collected was in the late 1990s, when he acquired the five film cycle about South African protagonists Soho Eckstain and Felix Teitelbaum by William Kentridge.