How Blue-chip Art Changed the Art Market

By Maike Moncayo

Borrowed by the finance world, the term blue-chip art designates high-value artworks that are considered to be a safe investment that is independent from the general economy’s ups and downs. As such, iconic artworks by the likes of Rothko, Picasso, and Van Gogh, that are considered “blue-chip”, are highly sought-after assets, which savvy collectors are willing to pay dizzying prices for.

It’s safe to say that blue-chip art has changed the art market, a transformation which was inaugurated by the now-famous Scull sale, one of the first record-breaking auctions at Sotheby Parke Bernet in 1973. When the collector couple Robert and Ethel Scull sold a selection of Abstract Expressionist and Pop Art artworks to skyrocketing prices which by far surpassed the initial price they had paid, it marked the beginning of a new era for the art market. A new era characterized by sensational record-auctions and an increasing investment mentality towards art collecting. Consequently, the blue-chip market of today does not compare to the art market of the Scull era. To begin with, and perhaps more evidently, since the 70’s, the prices for blue-chip art have exponentially grown. While the Scull auction made a total of 2 million dollars with the sale of 50 paintings, last year’s sale of Leonardo da Vinci’s painting Salvator Mundi sold for a record-breaking 450 million dollars alone. This clearly demonstrates the huge growth of of the art market. A fact that is also mirrored in Artprice’s Global Index®, which this year shows an average value increase for artworks of 30% since the index was started 20 years ago.

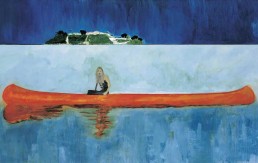

Secondly, the number of so-called blue-chip artists, too, has increased, ever more expanding to living contemporary artists like Peter Doig, Jeff Koons, and Gerhard Richter. Nowadays, profitability and a high return on investment are not confined to art that has proven valuable over time, such as works by dead artists. Thus, the notion of value creation itself as a process linked to and legitimized by art history has changed within the art world. In fact, artists snubbed by art critics can still be wildly successful at auction, showing that cultural and financial value don’t necessarily have to overlap in blue-chip art.

Furthermore, the traditional rules of the art market have changed with the evolution of blue-chip art. It was art market darling Damien Hirst, who first changed the game by sidestepping his representing gallery in order to directly sell his works at auction in 2008, raising a record 111 million pounds. Since then, other blue-chip artists like Jeff Koons have followed his example by breaking with the convention of the exclusive gallery representation. Ultimately, this has changed the ways in which galleries sell blue-chip art, as well as their customary relationship with artists.

However, despite its ever-expanding and field disrupting nature, blue-chip art remains bafflingly stagnant and conservative when it comes to the type of artists that get the biggest shares from this market: up until today, it’s mainly male and white artists. In 2017, only two women made the list of the top 25 most profitable artists, namely Agnes Martin and Yayoi Kusama. Hopefully, with more investors entering the art market, this tendency will be balanced out towards a more inclusive and diverse blue-chip art market.

Get your free copy of Artland Magazine

More than 60 pages interviews with insightful collectors.