Interviews

Chronicles of a War and an Art Scene in Peril. Interview With Bosnian Photographer Almin Zrno

By Adam Hencz

“I found myself in the middle of a war [….] with a rifle in my hand. […] I often daydreamed about returning to photography if the war ever ends.”

Almin Zrno

The siege of Sarajevo, the longest siege of a capital city in the history of modern warfare, lasted for almost four years in the early-mid 90s, a time when Serb nationalist forces intended to erase the city’s multicultural memory and cosmopolitan identity. Amidst atrocities and distress, on the night of August 25, 1992, The National Library was burned to the ground, resulting in the destruction of nearly three million books and rare manuscripts, a clear attack on the city’s cultural identity. Today, the site remains an iconic symbol of the city, and of war-torn Bosnia and Herzegovina.

More than a decade later, Greek-Italian contemporary artist Jannis Kounellis revived the Sarajevo building with grandiose installations and the Ars Aevi Museum Sarajevo engaged Almin Zrno, one of Bosnia’s most prominent photographers, to document this exhibition.

Zrno followed Kounellis through every stage of the installations’ production, thus creating a remarkable testimonial to the city’s resurrection. KUK Gallery in Cologne celebrates this cross-disciplinary artistic collaboration with an ongoing exhibition showing Almin Zrno’s fragile documentary work, JANNIS KOUNELLIS, Sarajevo 2004. On the occasion of the show, we sat down with the Bosnian photographer and talked about his swings between various genres of photography, the experience of living through the Bosnian War and his means of fighting against the newly established political system.

When did you get your start in photography and how did you grow interested in the medium?

As a very young man, at the age of fourteen or fifteen, I wandered into the photo cine club CEDUS in Sarajevo. I am talking about the 1980s and a country that no longer exists. At the time, in ex-Yugoslavia the only way to educate and develop yourself in the field of photography was to join clubs as I did. We did not have, and we still do not have specialised schools or a faculty where one can study photography. Photography is being taught only as a subject at the Academy of Fine Arts in Sarajevo. In CEDUS I learned the basics of photography and fell in love with the dark chamber. That feeling of seeing my work emerge from the developing tray was something I will remember as long as I live. As a member of CEDUS, I got the opportunity to participate in photography competitions at state level. Soon after, I was awarded for my work for the first time. However, being a very young man at the time, after five years, I left the world of photography and replaced it with music. I started playing with local bands, recording albums, touring around the country and then, somewhere in between, the craziness of the 1990s hit. I found myself in the middle of a war that started in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In Sarajevo, with a rifle in my hand, I experienced the longest siege of a city in the recent history of humankind. My only struggle was for life and sanity. Thinking about photography helped me a lot. I often daydreamed about returning to photography if the war ever ended.

The Bosnian war in the early 1990s kept you away from photography for a while. After almost four years, the siege was lifted at last. How did your attitude towards photography and its different genres change after the years of the war?

Less than a month passed from my wartime daydreams and my desire to return to photography and the opportunity to get a job as a photographer at the most influential newspaper in Bosnia Herzegovina at the time. However, if you want to live the life of rock’n’roll, you need to be able to live it as well. That is how I got into news photography and started working on up to ten assignments per day: from politics to sports, from portraits to features. And no matter how much I hated it, this is definitely the only path for anyone who truly wants to learn photography. A photographer must experience the daily drill of a newspaper. After three years, I started working for a monthly magazine that considered photography in a different way, giving me space for more creative freedom. Another three years later, I decided to leave the world of media and become a freelancer because at the time I already had a lot of work on the side that allowed me to lead a normal life. I was shooting covers of lifestyle magazines and I dived into the world of art thanks to the collaboration with the theatre and jazz scene, as well as my work with Ars Aevi Museum of Contemporary Art, and many other artistic encounters that fulfilled me as an author.

What assignments, reportages are the most memorable for you?

There is one assignment that is perhaps not the most important one, but to me, it is the most memorable. I told you that I spent the four years of war, filled with fear and terror, in Sarajevo. In 1999, four years after the war ended, I was asked to follow USS Theodore Roosevelt, the biggest warship of the US, stationed on the Mediterranean Sea. It was on an air campaign against Serbia, the country that had attacked Bosnia and Herzegovina and laid siege to its capital, Sarajevo. It was a surreal experience.

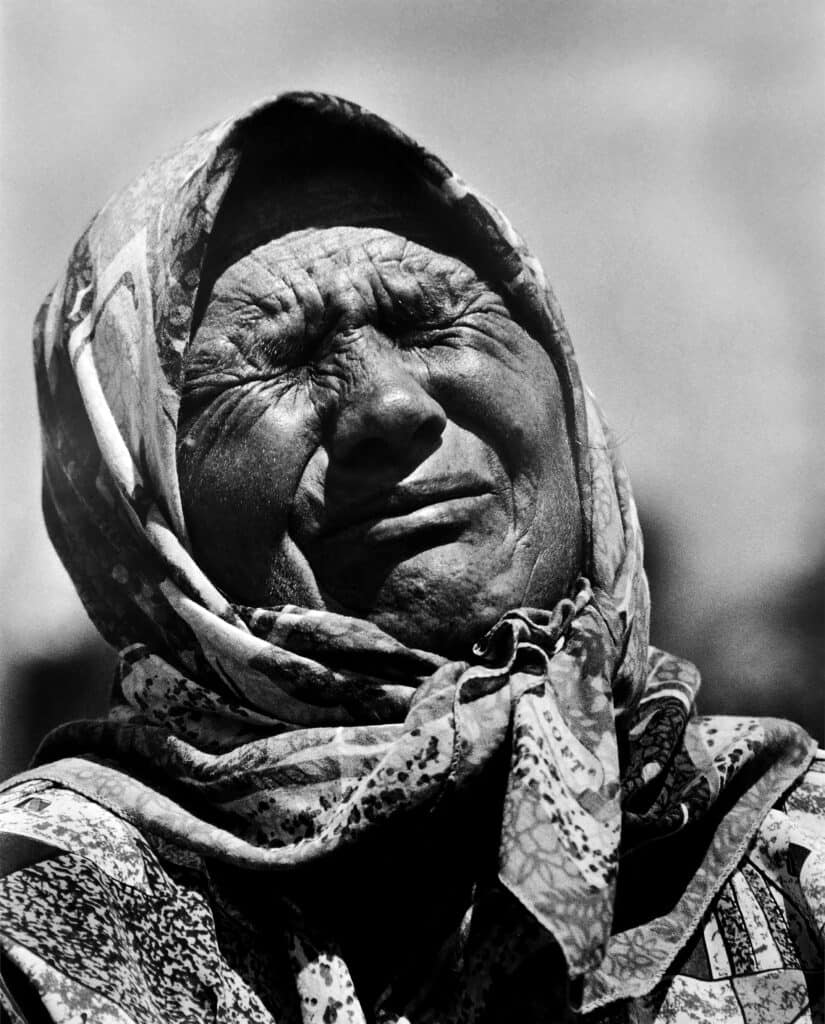

A few years later, in 2001, you shot the iconic image of Mother of Srebrenica, which became a symbol of powerful Bosnian women, and those in the quest for justice for the Bosnians who lost their family members during wartime. You referred to this portrait as one of the milestones of your life. Can you share a bit about that image?

This iconic photograph was made while I was working for the newspaper that I was telling you about earlier. It was made as a part of an assignment when I was reporting on one of the first mass burials of genocide victims in Srebrenica. It was a beyond painful experience to accumulate that amount of pain over time, while being forced to document what was happening in front of my bare eyes. This was still the age of analogue photography, so I was not aware of this photo before I came back to the office and developed it. It soon became my most wanted and the most cited photograph. The first time I had to sell the image for a fee, I was morally torn. At that moment, I realized that I couldn’t make my happiness on the account of someone else’s pain. After that, I stopped working on similar assignments. For me, photography is more than a way to make a living.

How would you describe the current photography and cultural scene in the not long ago war-torn Bosnia and Herzegovina?

Ugh… How can I even begin describing a scene that has been trying to wriggle out of the straitjacket that is the Dayton Peace Agreement for the past 25 years? Moreover, the country is fighting the newly established political system of conservatives that are pulling us backwards. In such an environment, the culture is the first one to suffer the blow, but it also strengthens those who are fighting for it and have a vision for connecting it to the world.

“The space in which I live […] is very conservative, divided, and filled with primitive populism.”

Almin Zrno

You said that you left the genre behind and pivoted from journalistic photography to the art world. What has been the hardest part of working with photography in a gallery setting?

I was attending the opening of my first solo exhibition in the Art Gallery of Bosnia and Herzegovina that dealt with the theatre and jazz scene through international festivals held in our country, wjen a man approached me to congratulate me, but also to tell me that I wasn’t the author of my photographs. I got confused and asked him for an explanation, so he asked me: “Did you set up this lighting, the scene, and the costumes? Did you bring two actors into this relationship portrayed in your photographs?” I told him that I didn’t, and he said: “Well, you see, you are not the real author.” I got mad, turned around and left him standing there, but I later got to think about everything he said. I accepted his logic and, from that moment forward, I decided to create all aspects of my work. Just like the painter approaches a blank canvas and starts filling it with colour, this is how I approach the composition of my photographs in my studio. But I must admit that I equally love to leave my studio in search of new subjects that I cannot recreate in it. The most challenging part of this job remains finding my own light and the language of photography that will be my own.

You started documenting installations as well, and in 2004 you worked with one of the founders of the Art Aevi Collection, Jannis Kounnelis, at an extraordinary site: Vijećnica, the destroyed National Library of Sarajevo, which was bombed and burned to the ground during the siege. How do you recall working with Jannis Kounellis and how do you feel about the exhibition in KUK Gallery?

The memories are still very much alive and filled with the energy that Jannis brought with him to the space of the destroyed Vijećnica, and the love and attention he invested into the 12 installations that were created at the site from scratch. These are experiences that change you and that open you up to different horizons. My task was to document each step, from the first book or the first stone that was brought to the site for the purpose of creating his art, to the final execution. This process lasted for a period of 30 days. I started very delicately, with a telephoto lens, to keep my distance and let him stay focused. But very soon we connected and established a mutual understanding for our work. He once described the material I produced in this period as something beautiful and unrepeatable, and how it was the first time that someone continually followed the creation of his work with a studious approach. I truly hope I was able to capture in my photographs the unique energy, commitment, work, and effort that were invested in these twelve grand artworks. I hope one can see and feel how the wounded Vijećnica embraced these works. A selection of these photographs was exhibited in KUK Gallery, and I think we created an amazing exhibition. I invite everyone to visit while it is still open.

Did you work on similar projects or collaborate with other artists?

In 2009, I had a similar collaboration with Braco Dimitrijević at the Venice Biennale. He was representing our country that year, and later we recreated the same installation in 2010 in the space of Vijećnica. In 2008, I was also documenting the exhibition of a grand Croatian painter Edo Murtić, again in Vijećnica. Starting from these three exhibitions, I composed my first monograph, titled Vijećnica.

Which techniques and equipment did you use for Apology of Eros, your second monograph?

As politics tightened the noose around the neck of culture, and as there were fewer and fewer events happening, I naturally sought a way out to a space that was my own. I was not satisfied with the development of the contemporary scene, not just in my country, but worldwide. There was little artistry and transcendence, little illusion of desire… It all came down to a gag, a hall, re-examination, documentation, and banalities of all kinds. Today still everyone is trying to be an engaged artist, even by force. The space in which I live, as I already mentioned, is very conservative, divided, and filled with primitive populism. In this atmosphere, working with nude photography is the most powerful act in my opinion. It is a way of fighting against the vulgarity which bombards us on a daily basis, whether on social media or in the mass media. This is my call for freedom, courage, love, humanity, empathy, the illusion of desire, the secret of eros, the escape from the banality of all kinds, consumerism, and greed. I began creating my own utopian world, and at the same time fearing the disappearance of everything that makes us human.

How do you think that fine art nude photography is viewed in today’s art world?

I believe it is all about the approach and the message that one wants to communicate as an author. Nude photography, in my opinion, must not be pursued for its own sake but it is a mere tool to tell a story behind the image. As a photographer, I want to take the viewer beyond, to transport them to some non-existent world, to the world of imagination, to my world, which is completely harmonious. I want them to feel the wind in my photographs, the music playing, everything that does not belong to my medium, to make them contemplate on it, or even to write a poem, an essay, perhaps a novel… Apart from the Apology of Eros, I also do classical nude photography, but never something bizarre, vulgar, or morbid. It is my fascination with the human body, its strength, beauty, fragility, and vulnerability. that brings these works about. We are always looking for some hidden meaning that is beyond ourselves, and yet we are all individually at the centre of the world, layed down by an unseen force of nature. To discover that meaning we need to embark on the path of self-realisation, we need to be brave and to become free.

Do you experiment with other types of photography? What inspires you these days?

I do, of course. The little boy side of me is very playful. I have not exhibited this in public yet, but I am close now to finishing a new body of work. We will see where it takes me. I love portraits, too. I am very committed to this discipline because I am preparing a big exhibition for the end of the year that will gather portraits of people from my community that I find extremely relevant and important.