Articles and Features

The Impossible Worlds Of M.C. Escher

By Adam Hencz

“We adore chaos because we love to produce order.”

M.C. Escher

Best known for his iconic optical illusions, impossible constructions defying logic and his prints playing with patterns and symmetry, Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher’s lithographs, mezzotints, woodcuts and wood engravings express a high level of technical expertise and meticulous attention to detail. His images of upside-down staircases and infinite structures appear on posters, album covers and sci-fi books, although people most likely do not know their origin. Escher remained a relatively unknown figure in the art world and students of geometry and crystallography are more likely to have encountered him than students of art history.

Maurits Cornelis Escher was never an outstanding student and his formal mathematical knowledge was limited to what he received in secondary school. However, his father George, who was a civil engineer, instilled in him a lifelong interest in mathematics and science. Born in the Netherlands in 1898, Escher spent most of his childhood in Arnhem. Aspiring to be an architect, Escher enrolled in the School for Architecture and Decorative Arts in Haarlem. While studying there from 1919 to 1922, his emphasis shifted from architecture to drawing and printmaking upon the encouragement of his teacher Samuel Jessurun de Mesquita. He began his professional life as a graphic artist, making woodcuts and lithographs.

in 1922, during a visit to the Alhambra, a fourteenth-century castle in Granada, Spain, Escher became fascinated by the geometric decorations of Moorish tiles, and was intrigued by the repeat patterns that exemplify Islamic art, and how repeated designs created visual puzzles. In the meantime, his half-brother Berend, professor of geology and soon-yo-be rector of the University of Leiden, kept him informed about the latest scientific literature in the field of crystallography. Several of Escher’s most known prints were inspired by these visual and theoretical insights as geometry and mathematics slowly became key elements of his work.

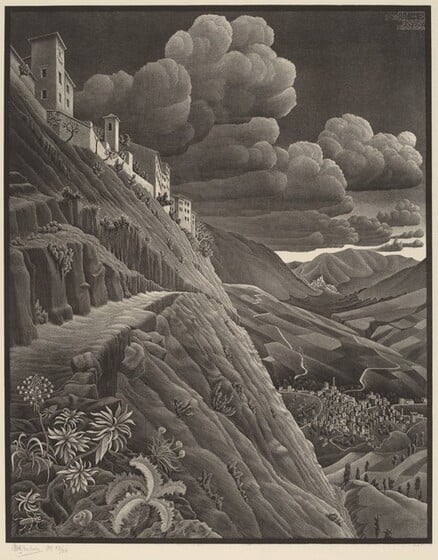

In 1924, Escher married Jetta Umiker, and the couple settled in Rome to raise a family. They resided in Italy until 1935, when growing political turmoil forced them to move first to Switzerland, then to Belgium. In 1941, with World War II under way and German troops occupying Brussels, Escher returned to Holland and settled in Baarn, where he lived and worked until shortly before his death. However, throughout his career, the main subjects of Escher’s early drawings and prints would be Rome and the Italian countryside where he used to spend the spring and summer months during his Italian stay.

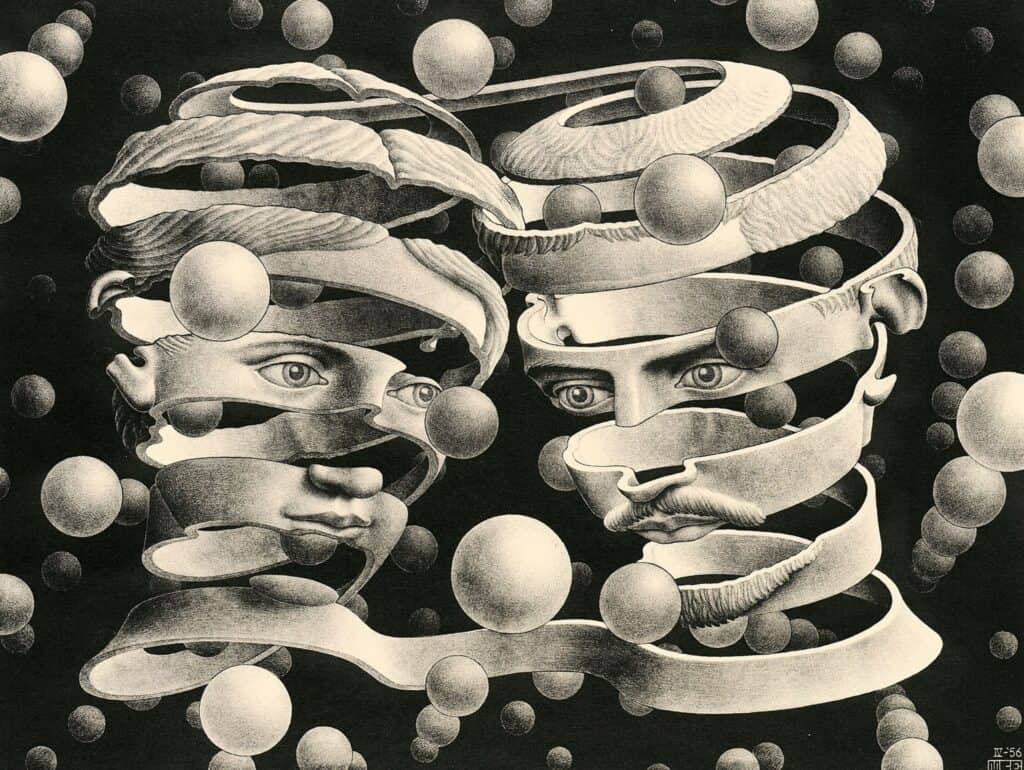

After leaving Italy, Escher’s interest shifted from landscape to something he described as “mental imagery,” often based on theoretical premises. He developed his practice into creating “invented places” which presented physical impossibility but followed the principles of perception Still Life with Mirror (1934) is one of Escher’s earliest prints to explore different levels of reality.

“My work is a game, a very serious game.”

M.C. Escher

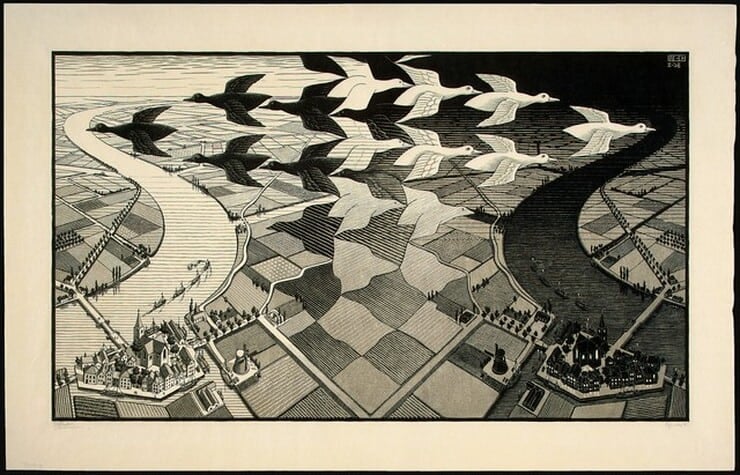

After returning to Alhambra in 1936, Escher would spend much of his life exploring the visual possibilities of the area of mathematics known as tessellation using geometric grids. To this rather stark abstract field of mathematics, Escher added a human and a fantastical dimension that incorporated animals such as lizards, dragon-like creatures and birds into his interlocking designs, replacing the abstract patterns of Moorish tiles with recognizable figures. He understood mathematics from a visual perspective and was interested in playing with symmetry and abstract, positive-negative geometric shapes. This lead to his theory on the “regular division of the plane,” which he described as follows: “A plane, which should be considered limitless on all sides, can be filled with or divided into similar geometric figures that border each other on all sides without leaving any empty spaces. This can be carried on to infinity according to a limited number of systems.”

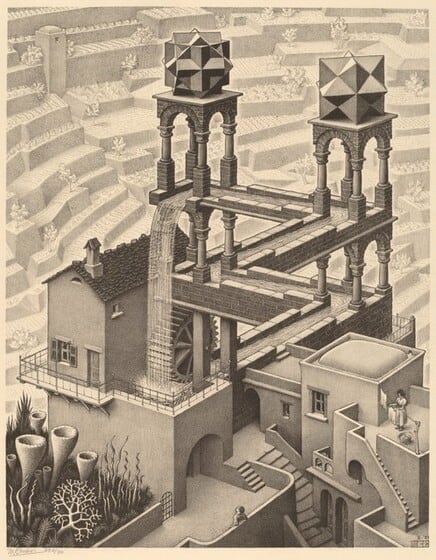

After the war, his compositions began to explore paradoxical placements and errors of perspective in structures that seemed plausible at first glance, but upon closer inspection were impossible to create in reality like his 1953 lithograph Relativity. He frequently employed a visual game in which he transformed a flat pattern into a three-dimensional object. In 1954, some of his engravings were exhibited in Amsterdam, coinciding with an international conference of mathematicians. The show was seen by visitors from all over the world, and from that time on, the dialogue that he maintained with mathematicians Roger Penrose and H.S.M. Coxeter became a source of inspiration for prints of optical illusions and representations of infinity.

Although parallels can be found between Escher’s work and Surrealism, he had no contact at all with the Surrealist group. He was not part of any art movement nor avant-garde. He lived a quiet life and was a one-man art movement standing outside the main currents of modern art. He did not become well known as an artist until later in his life and held his first retrospective show at the age of 70. From the other side of the spectrum, besides mathematicians and graphic artists, his works were celebrated in popular culture and he was adopted as a pioneer of psychedelic art by the hippy counterculture movement of the 1960s. Appreciation for Escher’s work has grown significantly in the 21st century and his work enjoys enduring popularity with the general public, with his works being exhibited across the globe.

Relevant sources to learn more

M.C. Escher Foundation

The Art of Repetition: Top 10 Pattern Artists