Articles and Features

John Copeland, ‘I Feel It In My Bones’, at V1 Gallery, Copenhagen.

In his 1996 book, ‘The Fate of a Gesture: Jackson Pollock and Post War American Art’, Carter Ratcliff makes a case for a certain lineage in American painting—beginning with Pollock’s famed drip paintings— that evokes a uniquely American “sense of limitless possibility” because they “draw the imagination into a region of boundless space.” In this provocative survey of one developmental perspective in postwar American art, Ratcliff traces not only Pollock’s career and those of his immediate peers, but also many subsequent painters in whose work he sees the same freeing tendency towards the infinite. He identifes what he characterises as an all-over or boundless quality that, he infers, extends past the physical bounds of the picture plane ad infintum. Ratcliff asserts, for example, that the repetitious boxes and cubes of Sol Le Witt’s signature creations resemble Pollock’s drip paintings because they could somehow go on forever and thus imply the infinite. Today’s spiritual heir can be found in Brice Marden’s diaphanous loops, apparently. Ratcliff’s thesis, ladies and gentleman, is that artworks in possession of these traits are therefore ‘free’ in ways that other kinds of painting are not.

All of which leads us rather circuitously through the weeds of scholarship to a cavernous warehouse on the Greenpoint side of the East River, just yards from the water’s edge—a possible destination for one of many tributaries Ratcliff’s idea has traversed. Here John Copeland exercises his twin passions for painting and motorcycle mechanics, practicing both in a fashion that leaves no doubt about what ‘freedom’, that most nebulous of concepts and somehow nowadays the colonised property of American-ness, might mean to him. He races the bikes too, travelling with his rig to race meets, where he hurtles around the track in competitive abandon. He’s quietly determined. Steely. He gets the bit between his teeth and goes very fast, though his zeal for this particular kind of in-the-moment presentness has seen him spilled from the saddle and almost cost him his life on more than one occasion. Past the rows of well-loved bikes, oily tools and finely calibrated machines, one comes to the painting studio—a vast space as high as it is wide and long—a massive demi-white cube that is both gallery, warehouse, and repository of countless hours of dedicated practice.

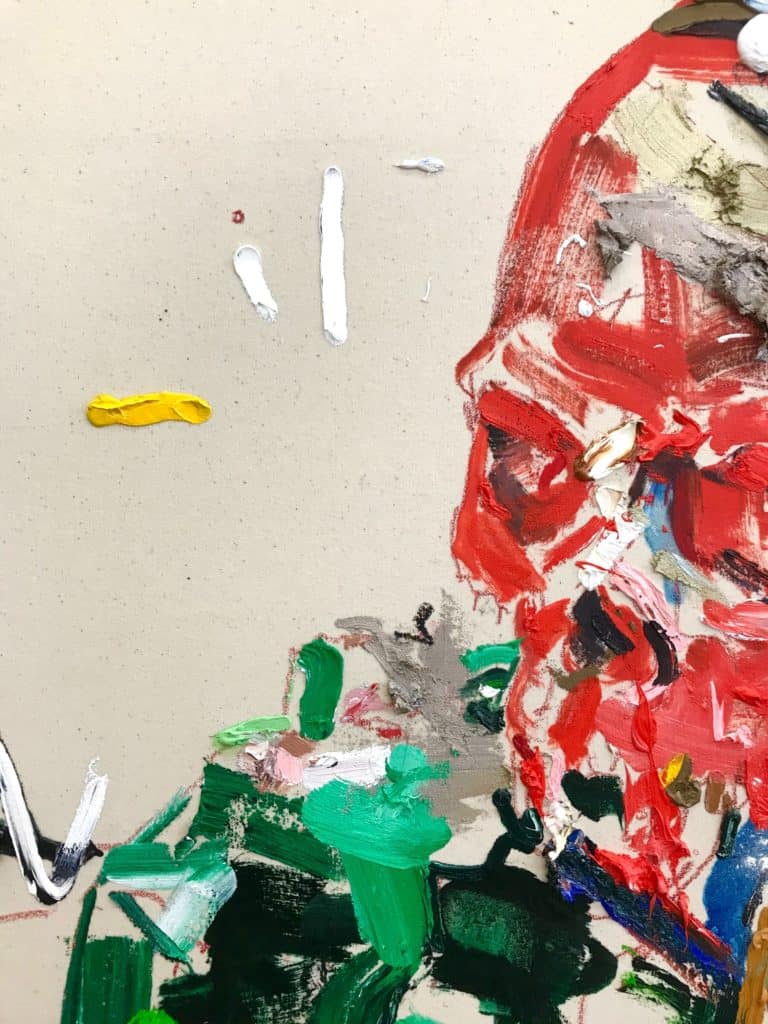

In his current exhibition at Copenhagen’s V1 Gallery, ‘I Feel It In My Bones’, his sixth solo outing there, Copeland has visited these many hours of studious improvement upon the paintings on display, principally in essaying a new, more open painterly style. Characterised by large swathes of creamy raw canvas, these works incorporate the empty ground as a key compositional element for the first time, upon which Copeland places his signature scenes of ambiguous or fractured narrative. He sources his pictorial inspiration from all kinds of ephemera; vintage magazines, postcards, boxes of old photographs he picks up from thrift stores and auctions. Profound or banal, in a way they’re all the same. He doesn’t know their back story nor does he want to. Are they interesting to him and do they represent some identifiable exemplar of how humans interact? Copeland’s protagonists are everymen; quotidian and ordinary and emblematic only of how we all exist in the world. His distant remove from them mitigates a need to tell their stories in a literal fashion, turning them instead into vehicles for pure painting, direct and unfettered.

“His trick is to give an impression of frenzy, when in actuality he exercises meticulous total control that really only masquerades as haphazard chaos”

But the works also tell a different story, the story of Copeland’s interest in paintings’ manifold purposes through the ages and his wish to plot a path for his own along this locus. For the sources are not merely pictures of people looking, talking, sitting, doing, wherever and whenever, culled from banal and leftover material culture, they are also taken liberally from the pages of art history. These tropes include motifs typically associated with Old Master paintings, the sacred and profane, and all fused together in a peculiar and casual classicism that includes the vanitas skull, the nude and the still life, redolent of the same symbolism, but emptied of it too, and repurposed for a world that also includes bikers, tattoos, girly mags, beer, barbecues on the beach, as well as countless other vernacular and arcane scenarios where ‘high’ can be employed to depict ‘low’.

Whatever the subject Copeland approaches each work with the same rigour. With brush, palette knife, direct-from-the-tube-like-cake-piping, his paint applications are alternately dry and scumbled and succulent. His trick is to give an impression of frenzy, when in actuality he exercises meticulous total control that really only masquerades as haphazard chaos. The expanses of raw canvas allow the viewer to share the artist’s enjoyment in paint’s tactility; linseed oil bleeds like chromatography and colors merge, wet-in-wet. But the raw linen also frames the compositions, suspending the flurried array of marks within the arbitrarily defined pictorial field. Extension beyond the perimeter is implied here not by a repeated motif pushing at the edges, but the sense of bottled energy that cannot be contained by them. In action movies explosions are sometimes depicted by lavish freeze frame special effects, whereby glass, fragmented shards, shrapnel and all manner of blast detritus are frozen in time, held for a split-second in a hovering halo of pieces around this or that hero, before the un-paused shock wave is unleashed. Copeland’s dizzying splashes of impasto are their painted analogue.

His practice has evolved to the point where he is able to leave more and more out. The reductiveness of the palette has resulted in heavy emphasis on his versions of the primary colours; there is a royal blue, almost electric; an uncut cadmium yellow of pure sunshine; one or two permutations of red on the scale between crimson and vermillion and a sumptuous forest green with the chlorophyll punch of concentrated wheatgrass. Blending these zesty colours is no mean feat, and by incorporating each into a single work, which Copeland does routinely, he somehow manages to neatly sidestep garishness.

And so back to our leitmotif once more. Are Copeland’s paintings free? Patently so. They manage to be both abstract and figurative, yet simultaneously neither. They are liberated from the petty bourgeois niceties of pictorial story telling, but also not overly bothered by the formal problems of abstraction; otherwise known as how painting can prove itself to be only pigment on a flat surface in ever-new ways (that are interesting). They capture the immediacy of his drawings, always a key starting point for the artist and an essential staging point in his process. One might even call them drawings—rendered with real directness in indulgent gobbets of paint. They have all the spontaneity of this kind of mark making with none of the limitations of not being quite ‘enough’, often the key accusation levelled at drawings, and the main differentiator in the hierarchy between the two. Copeland’s new works are both. They are a worthy outcome for gesture’s fate.

Relevant sources to learn more

V1 Gallery Website

John Copeland Profile on V1 Gallery

John Copeland profile on Artland

Giuseppe De Mattia’s fruit and vegetable stall at Matèria Gallery, Rome