Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: James Van Der Zee

By Shira Wolfe

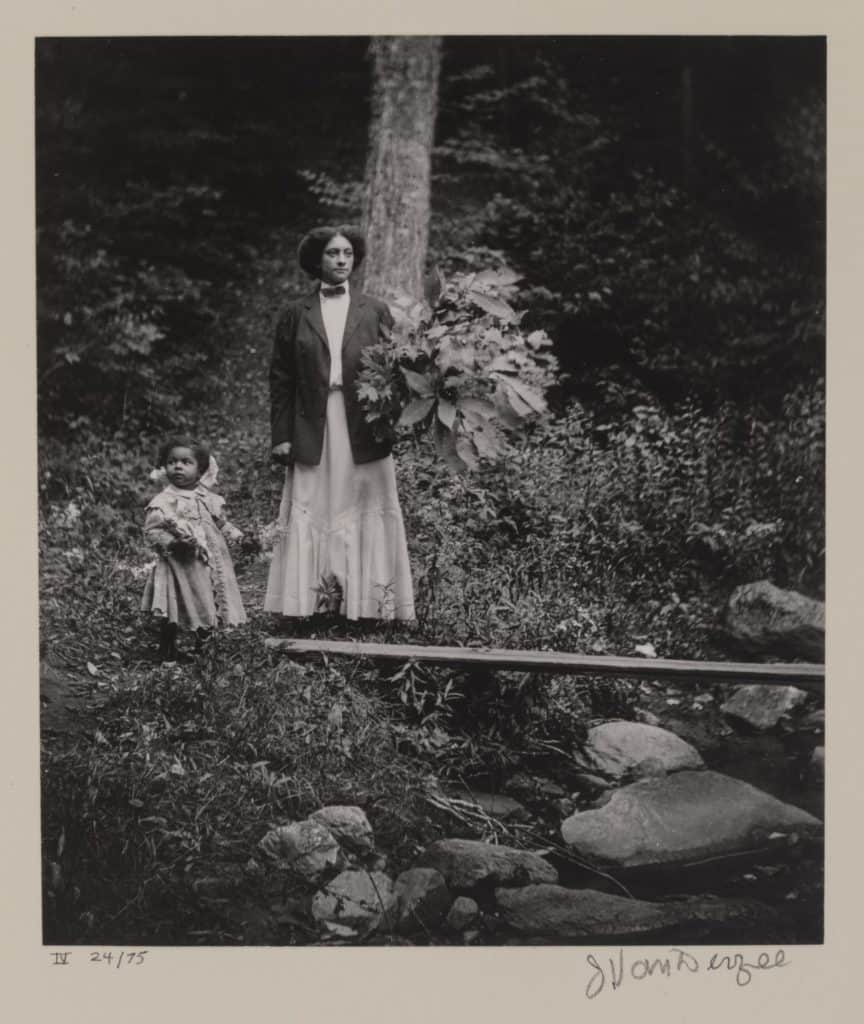

“I wanted to make the camera take what I thought should be there.” James Van Der Zee

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series features artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. Today’s lost (and found) artist is photographer James Van Der Zee (1886-1983), a figure who immortalised the Harlem Renaissance movement in photographs. Van Der Zee documented the intellectual, artistic, and everyday life in Harlem in the early 20th century as it emerged as one of the principal urban centers of the African American population.

James Van Der Zee’s Early Years

James Van Der Zee was born in Lenox, Massachusetts in 1886. Early on, he showed a great gift for music and he initially aspired to be a professional violinist. His other great passion was photography. At the age of fourteen, Van Der Zee received his first camera, with which he took hundreds of photographs of his family and his hometown. Van Der Zee was one of the first people in Lenox to own a camera, providing early documentation of life in small town New England.

In 1906, Van Der Zee moved to New York City where he, his father and his brother worked as waiters and elevator operators. But Van Der Zee was already a skilled pianist and violinist, and created the Harlem Orchestra together with four other musicians. In 1915, he moved to Newark, New Jersey, where he got a job as a darkroom assistant and as a photographer in a commercial portrait studio. It was 1916 when Van Der Zee returned to New York and moved to Harlem, just at the time when a large wave of black migrants and immigrants were moving to that part of the city. Van Der Zee chose to focus solely on photography, leaving behind the more uncertain life of a musician. That same year, he opened his first photography studio on West 135th Street. Two years later, he established the Guarantee Photo Studio in Harlem together with his second wife, Gaynella Greenlee.

Documenting the Harlem Renaissance

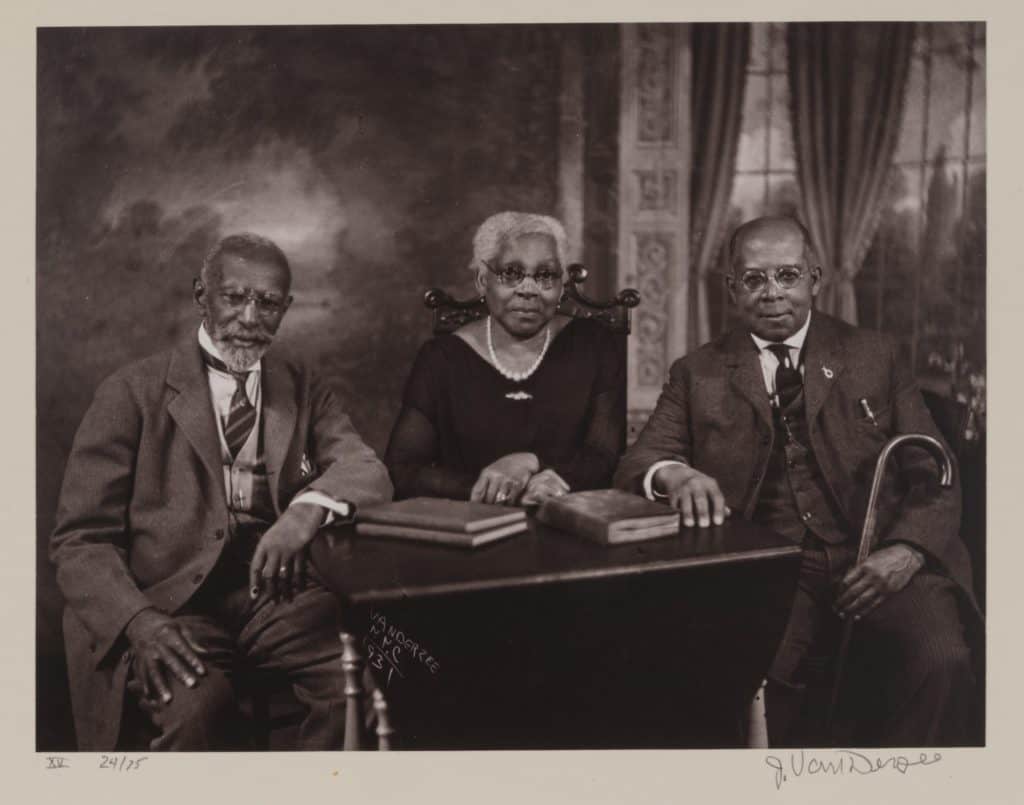

Van Der Zee recognised the burgeoning cultural life amongst his peers in this part of town, determining a moment in time that had to be captured.. The intellectual and artistic life in Harlem during the 1920s and 1930s was flourishing, and Van Der Zee produced thousands of photographs of the people of Harlem. In his studio, he created formal, posed photographs of Harlem residents and artists often wearing their best clothes and presenting their cultivated taste, in addition to street photography in the neighbourhood, where he essayed more free form works of cabarets, restaurants, barbershops, church services and street scenes. He once said: “I wanted to make the camera take what I thought should be there.” It didn’t take long for Van Der Zee to become the most successful photographer in Harlem, and his subjects included the likes of activist Marcus Garvey, entertainer and dancer Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, and poet Countee Cullen.

The residents of Harlem entrusted Van Der Zee with the documentation of their important personal life events, including weddings, funerals, and social events. The dreams and aspirations of the Harlem people were the dreams and aspirations of Van Der Zee as well – together, they strove for self-determination, racial pride, and visibility in their city and country. The aim of Van Der Zee’s photography was to capture the personality, character, and individual beauty of his subjects. His work was amongst the most eloquent advocates pushing for greater visibility and validation of African Americans in the emergent cities of the north in the decades after the Civil War.

1930s – Decline in Work

By the early 1930s, Van Der Zee’s income from his photography work started to decline. This was in part due to the economic crisis of the Great Depression which effected the circumstances of many of his customers, and in part due to the growing popularity of personal cameras, which were becoming increasingly affordable for more mainstream consumption. Van Der Zee managed to get by with his photo studio where he shot passport photos, did photo restorations, and took on other miscellaneous photography jobs. He continued working like this for several decades.

“It’s easy to think that you know Harlem — a place with an iconic history, where movements were born, parades were protested, and that black Americans called mecca. Even if there weren’t countless movies, poems, art, spoken lore and books about Harlem, you could visit it today and still feel a lingering sense of that history, despite the gentrification tsunami that has washed over all of New York City. But what you could not do is see Harlem the way photographer James Van Der Zee saw Harlem…” The New York Times

James Van Der Zee Rediscovered

James Van Der Zee’s work was rediscovered in 1967 by photographers and photo-historians, prompting well-deserved attention which extended far beyond his Harlem community. In 1969, the Metropolitan Museum of Art exhibition Harlem on My Mind included numerous key photographs by Van Der Zee, thus bringing him to the attention of the art world, even though the photographer himself had retired the year before due to a declining market for his type of portraiture. Though the exhibition sparked controversy as many claimed the show to be a culturally patronizing, white man’s view of Harlem, it was also one of the first times African American life and culture were featured in photographs – a medium not yet embraced by the art establishment – in an exhibition that would reach many people. With this renewed surge of attention, Van Der Zee shelved his plans to retire, and in his later years he photographed numerous important figures and celebrities including Jean-Michel Basquiat, whom he famously captured in a pensive, intimate portrait when the artist was just 21 years old, and Van Der Zee himself was 95.

Today, James Van Der Zee remains one of the foremost photographers of his generation. giving the world a visionary insight into the Harlem Renaissance movement, whilst also being a key figure in the shaping of that cultural moment.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more about James Van Der Zee and the Harlem Renaissance here:

Art Movement: Harlem Renaissance – Artland

Williams College Museum of Art

Discover more of our Lost (and Found) Artists here: