Articles & Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series:

The Visual Poetry of Maria Lai

“What does sewing mean? A needle enters and exits something leaving a thread behind: a trace of its path which joins places and intentions”

Maria Lai

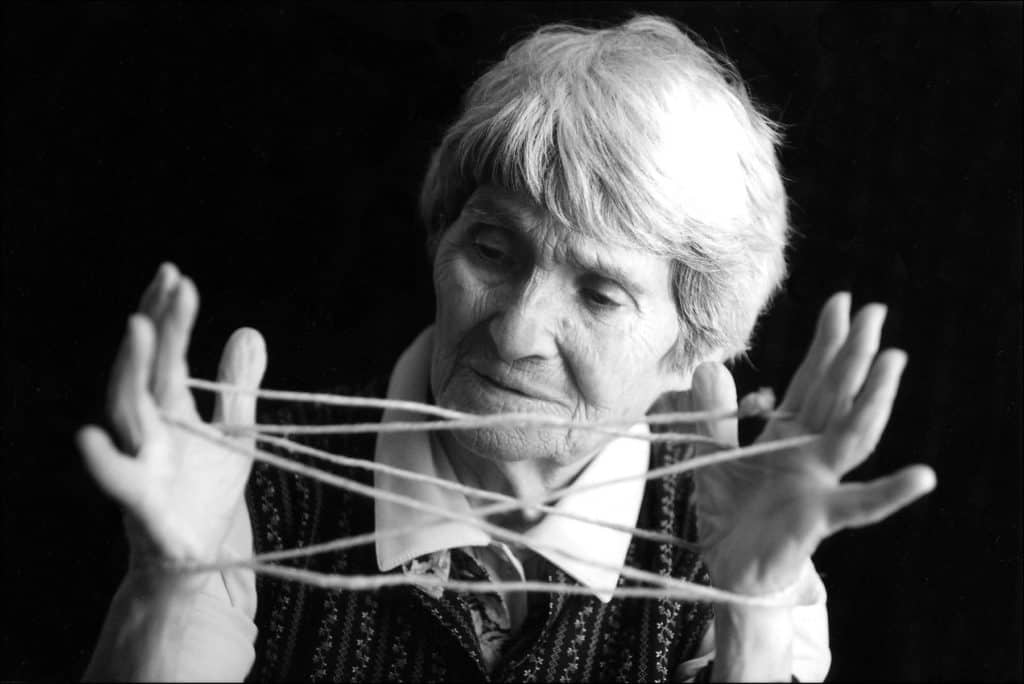

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their careers. This week we feature the groundbreaking work of Sardinian artist Maria Lai, a life’s work that started from the most ancient traditions of her remote home region to become universally symbolic.

Partly due to the little recognition given to most female artists of her generation, and partly to meet her own need for deep introspection and contemplation, Maria Lai’s artistic career only flourished after the age of fifty.

Moreover, it was only in 2017 thanks to two posthumous exhibitions – the artist passed away in 2013 – at Documenta 14 and then the Venice Biennale that Lai’s singular voice has come to receive its well-deserved international attention.

“It doesn’t matter if you don’t understand, just follow the rhythm”

Maria Lai

Maria Lai’s Early Life

Beyond white beaches and clear Mediterranean waters, there is another Sardinia often neglected by the legion of tourists that flock to the island every year; it is the inland region, with its barren, rocky and deserted landscape and flocks of sheep, where the modern world seems to have left no trace and an archaic atmosphere endures.

In 1919, in this timeless land, the artist Maria Lai was born in a remote village perched on a mountain and named Ulassai. Too delicate for the harshness of the place, Maria spent almost her entire childhood with some close relatives who also lived in an isolated environment, but much closer to the salubrious sea air. Without a means to travel to the school, Maria grew up in solitude and silence with only her pencils for friends, where she began to show early a precocious talent for drawing.

When finally she moved to Cagliari to attend secondary school, the Sardinian capital city’s teeming atmosphere proved to be too overwhelming for her and school life itself shocking: to some of her teachers and peers, she appeared maladjusted and with learning difficulties. Nevertheless, what could have proved to be a disastrous experience turned out to be an illuminating one thanks to an exceptional teacher, the writer Salvatore Cambosu, who sensed Maria’s artistic potential and revealed to her the beauty of Latin and poetry – a medium she knew nothing of – unveiling the power of words, and the rhythms they conjured in verse compositions.

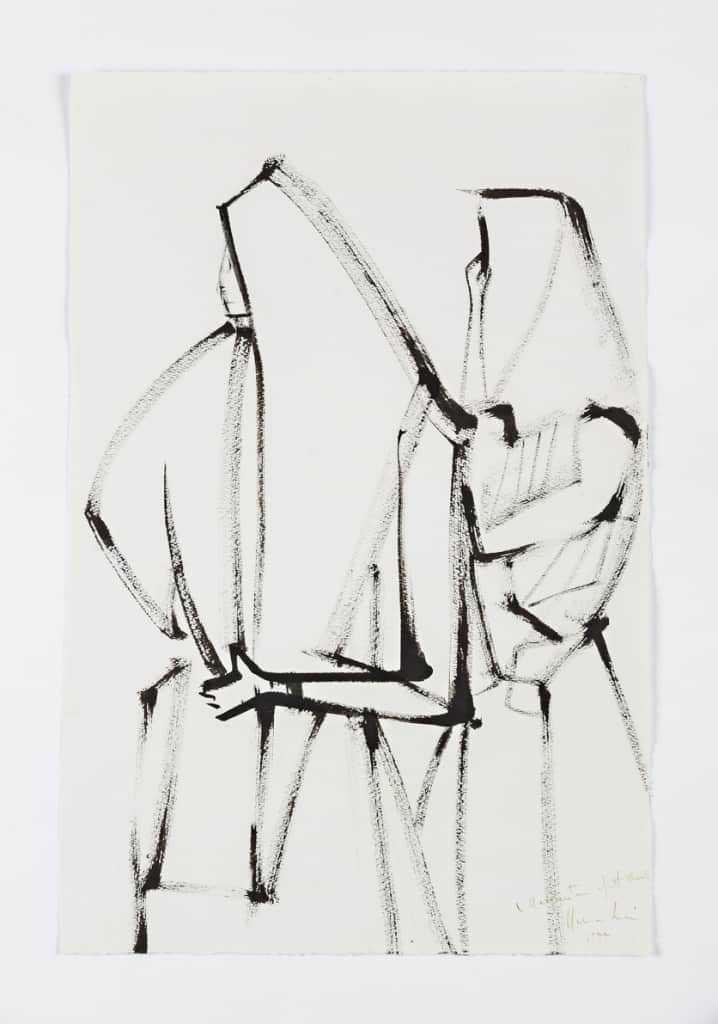

Maria’s family was relatively wealthy enabling her the considerable privilege of pursuing her studies to escape the housewife’s future she was otherwise bound to follow. Determined to explore new artistic languages, she put aside her shyness and reticence and enrolled in the Arts high school in Rome. On the one hand, she developed remarkable drawing skills and made inspiring connections with great sculptors of the time but, on the other hand, she also began to realise that being a woman in the art world would not be easy at all, even more so in the relative backwater of Sardinia.

For this reason, Maria used the outbreak of the Second World War as a perfect excuse not to return to her native island, but to move to Venice instead, turning Europe’s misfortune into a personal opportunity. It was only after the admission to the Academy of Fine Arts that she discovered she was to be the only female student.

Her initial enthusiasm and high expectations – especially regarding the sculpture course held by the artist Arturo Martini – soon collided with reality: a deeply chauvinist art system in a fascist society. Disappointed and disheartened, in 1945 Maria returned to Sardinia where she began to teach drawing classes to children, with her own practice limited to drawing portraits and scenes of daily life.

Stepping back from the art world

The years she spent in Sardinia were not easy ones. The war had left the region in a poor economic and social condition, as well as heavily affected by banditry; violence was commonplace and after several kidnapping attempts, bandits took the lives of many members of Maria’s family.

In search of a safer place, Maria moved back to Rome where, in 1957, she had her first drawings exhibition at the gallery “L’Obelisco” a vibrant cultural hub run by Irene Brin, as well as the first commercial gallery to reopen after the war. The showing proved to be successful and gave her significant recognition not only from collectors but from national cultural institutions as well; but just when it seemed to be the right time for her career to flourish, Maria suddenly decided to withdraw from the art scene altogether.

For ten years she kept a distance, but what could have seemed like surrender was in actuality the only means to truly find herself and her artistic voice – the only way to gather a creative energy that was about to explode.

First of all, Lai rediscovered a very deep connection with her origins and began to explore the ancient Sardinian traditions and legends, developing a unique language synthesising myths and archetypes, a pursuit simultaneously primitive and universal.

Moreover, she approached poetry again, engaging with literary circles, and finding inspiration in the alternating rhythms of words, and in particular the resultant punctuations of silence.

A new beginning

During the 1960s, Lai developed a distinctive artistic voice and conceived a new form of art that she did not present publicly until 1971. In her early fifties, she was finally ready to express her mature artistic voice.

Though familiar with contemporary artistic trends and close to the emerging interest in raw and organic materials of first Art Informel, and then Arte Povera and Conceptual Art, Maria Lai was able to trace her own path and to filter these other experiences through a marked individual sensibility. Definitively abandoning traditional drawing, the artist found in the use of thread her ideal means of expression which, in fact, runs through her body of mature work as both literal and metaphorical leitmotiv. To Lai, thread and twine symbolise the coming together of elements, the establishing of connections. They convey notions of bond and relationship, and, importantly, a link with the past.

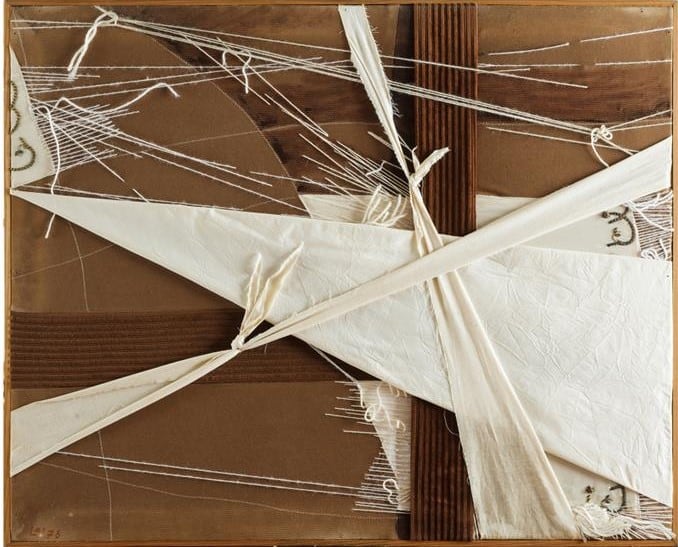

Lai created a series of works called Telai (“Looms”), colourful and ethereal conceptual objects made of wood, scraps of fabric and twine where warp and weft are arranged with complete freedom of composition, resulting in almost geometric abstractions. The act of weaving was an archaic and purely female gesture, functional and creative at the same time, and deeply rooted in ancestral Mediterranean myths – one just has to think to Penelope’s loom in the Odyssey or the mythological Parcae who controlled the metaphorical thread of life of every mortal and immortal being. Through radical modern art-objects Maria Lai transformed these themes into an original reflection on the meaning of community, a bridge between tradition and innovation, between history and the present. Furthermore, the loom allowed the artist to create rhythm through alternating filled and empty spaces.

Her entire work is imbued with poetic and narrative elements. Going back to the etymological meaning of the term ‘poet’ – that from the Greek literally translates as ‘creator’ or ‘maker’ – Maria Lai embodied both the roles of a poet and crafter, building an entirely new vocabulary of stitched marks and words.

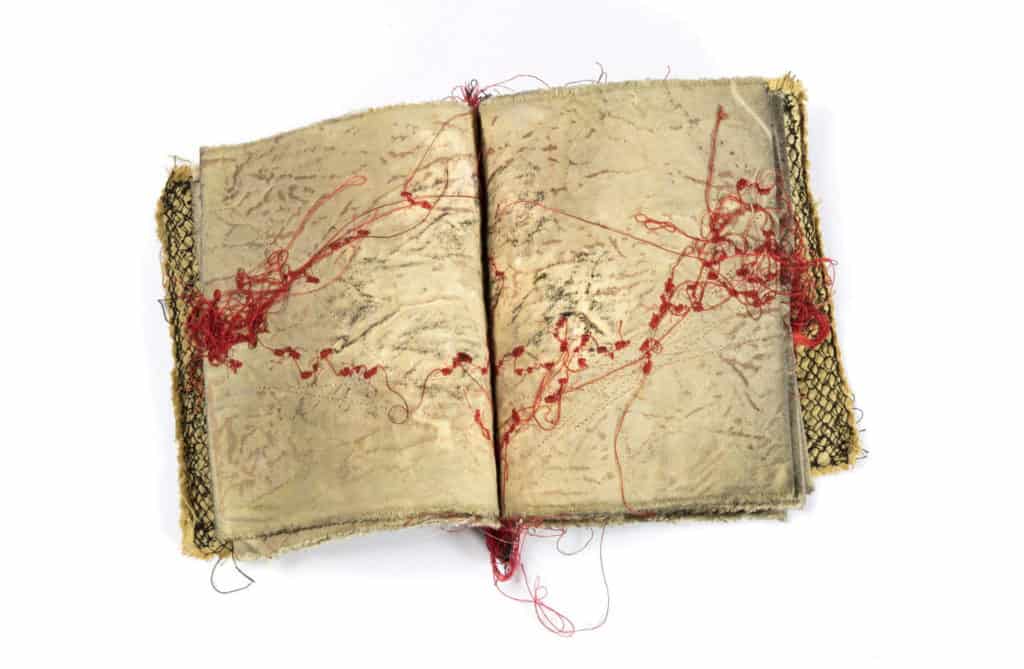

In the Geografie (“Geographies”) series, the artist sewed large fabric compositions resembling imaginary maps where embroideries represent planets, constellations, and invented universes; while her Libri (“Books”) are surreal objects, suspended between reality and imagination, with cloth pages and words made of tangled threads, illegible scriptures like encrypted tales.

Lai’s astonishing artistic transition did not go unnoticed and the Sardinian artist began to showcase her work in museums and galleries, and even took part in a group show at the Venice Biennale in 1977.

Binding to the Mountain

In 1981, Ulassai’s mayor commissioned Maria Lai with a war memorial; a commission the artist resolutely refused, proposing instead to create a monument for the living instead of the fallen. There was an old local legend, an oral history passed to the children generation by generation – a long time ago a little girl fortuitously escaped a landslide by chasing a blue ribbon carried by the wind. The artist, who considered the ribbon metaphorical of human relationships, conceived an idea that brought local institutions into chaos. Her intention was to physically tie every house in the village with each other with a sky blue ribbon which was then to be attached to the peak of the mountain overlooking the town.

Complicated negotiation and public interviews took about half a year since the village was tormented by long-standing feuds and disputes but, eventually, they reached an agreement: the people were to tie knots between houses whose owners were bound by friendship, they would hang a loaf of a typical bread called ‘Pane Pintau’ to symbolise strong affection and love, while to express conflict the ribbon would be pulled taut around the corners of the buildings, as a symbol of strained relations between neighbours or families.

On September 8th, 1981, the whole village participated in the project and, using a thirty-kilometres-long blue ribbon, unveiled the network of complex relationships to eventually bind itself to the mountain that represented to the community both a shelter and a fatal threat.

The evocative photography series by Piero Berengo Gardin, named Legarsi alla Montagna (“Binding to the Mountain”), remains as a documentary of this innovative and ephemeral artwork, simultaneously a performance, sculpture and monumental piece of land art. The performance was a tribute to Maria Lai’s origins and local folklore but, most of all, it debunked the idea of art as individual expression: not only did the audience interact with the artist but also participated in the planning of the project, eventually both participating in the execution and ultimately even becoming part of the artwork itself. This collective action, initially underestimated by the critics, is today regarded as a seminal example of Relational Art – before the term was even coined in 1998.

In 2006, as the culmination of the ambitious project that Maria Lai and the community of Ulassai had collectively cultivated and brought to fruition, the village opened a unique museum of contemporary art, Stazione dell’Arte (literally ‘Art Station’), and what once was just a cluster of houses on the periphery of the world has now become one of the main cultural centres in Sardinia.

In 2019, on the occasion of the centenary of her birth, the museum MAXXI in Rome held a major retrospective of Lai’s work marking the last step in the acknowledgement of an artist that looked at the world with the eye of a child and chose to mend its many schisms with poetic stitches.

Relevant sources to learn more

Maria Lai Archive

Museum Stazione dell’Arte

Maria Lai at Documenta 14, 2017

Maria Lai at Venice Biennale, 2017

Maria Lai at Maxxi, 2019

For previous editions of the Lost (and Found) Artist Series, see:

Saloua Raouda Choucair

James Van Der Zee

Ming Smith