Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. This edition’s featured artist is McArthur Binion. Binion was vastly underappreciated for most of his career; now in his 70s, he is finally getting the recognition he deserves.

Every artist must invariably deal with pigeonholing throughout their artistic career. And when they don’t seem to really fit into any particular box or definition, this can result in misunderstanding and underappreciation. For some artists, like McArthur Binion (b. 1946), it appears their authentic artistic voice is not understood to really fit anywhere, causing them to work mostly under the radar. Binion’s work was deemed too emotional to fit in with minimalism, yet too minimalist to be understood in terms of identity politics. The artist himself also refused to be pushed into any of these categories. For over 40 years, Binion, who was the first African-American artist to graduate from Michigan’s Cranbrook Academy in 1973 where he met fellow artists like Dan Flavin and Ronald Bladen, has created deeply emotive, autobiographical abstract works realised in tightly composed grid patterns, which are only now being exhibited and sold widely around the world.

Interior Emotionality – The Poet Becomes a Painter

McArthur Binion started art school as a creative writing major, planning to become a poet. When he dropped out of school at 19, he took a job as an associate editor for a magazine in Harlem. One day, he was sent to deliver a package to the president of the Museum of Modern Art where he came face to face with the first painting he ever saw in his life. He was floored and took up drawing and painting classes two years later. He describes these art classes as the most emotional experience he had ever gone through at the time. He worked on his craft obsessively, drawing 40 hours a week for two years straight to catch up.

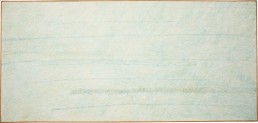

In an interview with Artspace’s Loney Abrams, he describes how his art comes from the same place as poetry and jazz music – from the interior emotionality of him. This is, and always has been, the starting point and the core of his work. Therefore, while many people would try to place Binion somewhere by defining him as a minimalist artist, Binion always knew his work was far too emotive to fit into that category. On the other hand, many people would immediately read his work as being about identity and race because he is a black artist, even though this is not the point for him. Binion moves far beyond the confines of identity and race politics in his art, stressing that there is no historical line running through him and that he completely made himself up, invented himself, as an artist in the art word. After all, Binion had no knowledge of the history of art or art in general prior to that first encounter with paintings in the MoMA. His work comes from his personal history. At art school, he started out by working with oil paints like everyone else but soon abandoned this as he realised oil paintings were made by people in museums, and he came from a very different place. He wanted to break with these art historical traditions because he felt he did not come from there. In order to do this he started innovating with wax-based crayons often used in lumberyards and steel mills, on aluminum. This was his preferred method in the ‘70s in New York after he finished art school.

New York in the ‘70s

Binion was never one to just let things happen to him, or not happen to him, for that matter. He speaks lucidly about the art world back in the ‘70s and how he had a very clear understanding of how it worked and what his position was there. In fact, he takes partial agency over the fact that he was not often shown in galleries while living and working in New York in the ‘70s. He turned down many offers to show his work because he felt people didn’t understand his art and wouldn’t present it in the right way. He knew, even as a young artist trying to make it in the city, that his art wouldn’t be seen the way he wanted it to be seen, and it wasn’t worth it for him to just play the game. He cared too much about his art.

However, there is no doubt that Binion was part of the New York art scene back then. He knew everybody and was invited to all the art world parties and events, but, as he explains, there were barely any black people downtown in those days apart from Romare Bearden, and though he attended loads of events, he didn’t always want to be the only black person there. Finally, in the ‘90s, Binion left New York and relocated to Chicago. New York had become too expensive and it was too hard to get his work done.

An Unstoppable Force in Chicago, and Newfound Art World Recognition

In Chicago, Binion found the right environment to focus completely on his art without the same financial struggles and distractions of New York. Here, he maintained a rigorous work schedule, leaving the studio around 7 am and finishing work around 4 or 5 pm every day. He also managed to raise his two children on a teaching salary. So when recognition started coming around 2012 with solo exhibitions at Kavi Gupta in Chicago, the Contemporary Art Museum in Houston, and Galerie Lelong in New York, continuing with his 2017 exhibition at the Venice Biennale, his representation by Lehmann Maupin gallery since 2018 and works selling for up to $450,000, Binion was more than ready for this new phase, albeit with a healthy dose of wisdom and cynicism. For him, his art must always remain on his own terms. Nobody can tell him how he should talk about it and how he should present it.

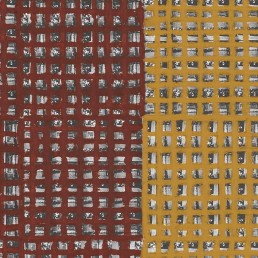

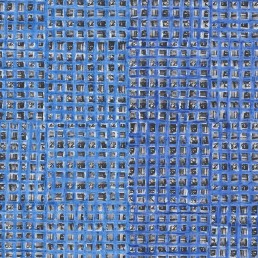

DNA Paintings, Hand: Work and Beyond

Binion speaks about using the geography of his life as the ‘under conscious’ and ‘emotional genepool’ of his work. His series of ‘DNA paintings’ combine personal items such as the artist’s birth certificate and names and numbers from the phonebook he kept between 1972 and the 1990s with sepia ink and gridded cross-hatching formed by paint sticks. Names from the New York art scene are concealed beneath the grids, names including ‘Basquiat’, ‘Dan Flavin’ and ‘Mary Boone’, among many others. These works speak to the times before Internet when communication between people, even in a metropolis like New York, was far more intimate. Everyone Binion knew was recorded in this phonebook, and now they are immortalised in his canvases.

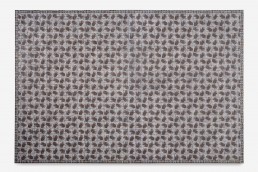

Binion has plenty more to say. Only now does he feel like he is creating his best work, and the ideas keep flowing. His recent exhibition ‘Hand: Work’ at Lehmann Maupin (through 2 March 2019) presented a series of paintings with tiled hands as the base layer, subsequently covered with crayon and oil sticks. Hands represent a place of origin for Binion, they too are markers of our personal DNA. For his next project, he plans to combine these hands with the phonebooks from his ‘DNA paintings.’ For the artist who started out as a poet working tirelessly to perfect his craft, it seems that narrative and medium have finally found just the right equilibrium.

McArthur Binion will have several solo exhibitions in 2019:

- ‘Hand: WorkII’, Lehmann Maupin Hong Kong (May 22 – July 6 2019)

- ‘Hand: WorkII’, Lehmann Maupin Seoul (May 24 – July 13 2019)

- ‘McArthur Binion, Ghosts: Rhythms & Haints’, Mississippi Museum of Art (October 12, 2019 – February 19, 2020)

His works are in many public and private collections, including the Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, MI; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit; Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art, Kansas City, MO; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York; National Museum of African American History and Culture, Washington, DC; New Orleans Museum of Art; The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; Wayne State University, Detroit; and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.