Articles & Features

Lost Architecture.

Iconic Buildings That No Longer Exist

By Tori Campbell

Lost Architecture

Some of the grandest and magnificent buildings of our cities’ pasts remain only in photographs and memories; as time, war, natural disaster, and neglect can lend a hand in their ultimate destruction. While some lost architecture is the result of public demand for demolition and development, much of it takes place despite community outcry for protection, occasionally leaving indelible traces on our cities resulting in new laws and mandates of architectural preservation for centuries to come. Explore with us some of the most iconic and contested pieces of lost architecture from around the world.

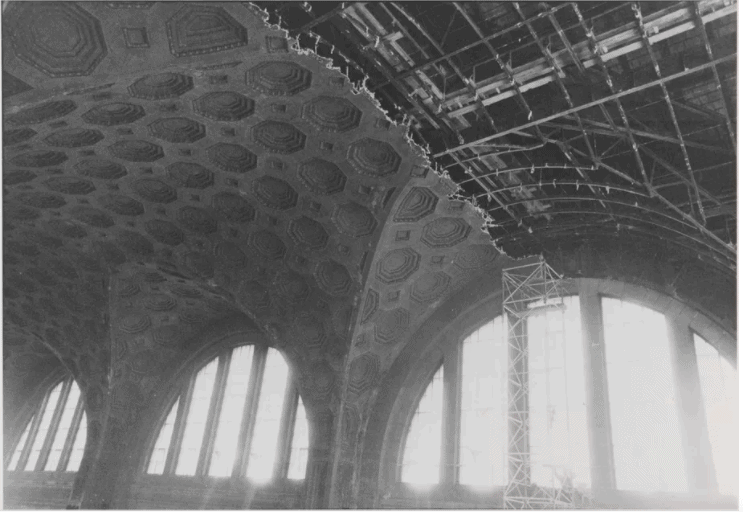

Pennsylvania Station, New York City: 1910 – 1963

One of the most contested and continuously bemoaned pieces of lost architecture is the original Pennsylvania Station in New York City. Built in 1910, the original Beaux-Arts building was a grand railroad station that suitably welcomed travellers into the international city. Featuring classical columns, pink granita, and high ceilings, it was demolished in 1963 to make room for the hideous Madison Square Garden and Two Penn Plaza. The public outcry resulted in the New York Landmarks Law, saving many future buildings and sparking widespread interest in architectural preservation in the city for the first time. A newly remodelled Pennsylvania Station just reopened in late 2020.

Crystal Palace, London: 1851-1936

Built for the Great Exhibition of 1851, what is now considered the first World’s Fair, London’s Crystal Palace has gone down in architectural history as one of the most impressive engineering feats of its time. Constructed with cast iron and sheet glass, the massive 1,851 foot (564m) long, 128 foot (39m) high building was an icon of the industrial revolution, proclaiming to the world a new order while hulking at over three times the size of St. Paul’s Cathedral. Designed by Joseph Paxton, the Crystal Palace held the 14,000 exhibitors of new technology, itself a marvel of plate glass never seen before at such a scale. Unfortunately, in 1936 the Palace caught fire and was destroyed.

Netherlands Dance Theater, The Hague: 1987 – 2015

The first major project built by the famed architect Rem Koolhaas and his firm OMA opened in 1987. The Hague’s Netherlands Dance Theater was exemplary of Koolhaas’ innovative approach to architecture, displaying an engineering marvel with a curved roof that provided exceptional acoustics in the auditorium. Also notable for its affordable nature, built for only 8 million dollars, the frugality of the structure lent it to a quick decline and public dissatisfaction. The project was demolished in 2015 and is the site of what will be a new cultural centre and performing arts theatre.

Cornelius Vanderbilt II House, New York City: 1883-1926

Built for the eldest grandson of the business magnate, the Cornelius Vanderbilt II House in New York City was, at its construction in 1883, the largest private home in the city, and remains the largest ever built. Boasting 130 rooms, the building found at the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street was an effort to outdo Vanderbilt’s competitors by displaying opulent wealth after buying up the entire city block and building a seven-story mansion with a stable and private garden next door. Unfortunately, the owner suffered a severe stroke that resulted in his untimely death only sixteen years after the home’s construction, and due to unmanageable upkeep, the home was sold to developers only forty-three years after being built. The Bergdorf Goodman department store now stands where the Cornelius Vanderbilt II House once stood, and the property’s gates now guard the Conservatory Garden in Central Park.

Jorba Laboratories, Madrid: 1970 – 1999

Colloquially referred to as ‘The Pagoda’ due to its aesthetic similarities to the classically Asian built form, the Jorba Laboratories building, designed by Miguel Fisac, was an example of rationalist design. Found right outside of Madrid, the laboratory campus featured square, offset floors, stacked to create a building that can be seen in multiple ways depending on light and time of day. Unfortunately, in 1999 the developers decided it would be financially beneficial to build a larger building onsite, and the original ‘Pagoda’ was demolished despite public outcry.

Sutro Baths, San Francisco: 1886-1966

Film of revelers at the Sutro Baths by Thomas Edison, 1897

Opened in 1894 on the cliffs outside San Francisco, the Sutro Baths were the world’s largest indoor swimming establishment. Founded and owned by wealthy former mayor and entrepreneur Adolph Sutro, he opened the bathhouse to give the city’s residents an accessible recreational institution on the outskirts of their city. Extremely popular, the Sutro Baths were well attended for decades before the Great Depression, when funds for upkeep halted and the baths suffered. By 1964 the site was bought by developers, aiming to turn the location into high-rise and high-rent apartments. A fire, likely started by arson, swept the remains of the baths in 1966, leaving ruins that can still be visited today.

Second Imperial Hotel, Tokyo: 1923–1968

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel in Tokyo was an exceptional example of his work, showing his architectural group’s famous style on a scale that was not often seen outside of the private homes of the American Midwest. Inspired by the work of his apprentice and associates: Arata Endo, Marion Mahony, and Walter Burley Griffin, the Imperial Hotel was designed in Maya Revival Style – incorporating a pyramid-like structure as well as ornamental Mayan motifs. Opened in 1922, just one year later a monumental earthquake that rocked central Tokyo, sparing the Imperial Hotel. However, the hotel bore its own share of hardships, having been damaged in World War II and eventually slipping into decay as time and neglect took its toll. In 1967, the hotel was demolished in favour of a high rise replacement, though the entrance courtyard of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Imperial Hotel was recreated near Nagoya as part of the Meiji-Mura Museum.

La Maison de Peuple, Brussels: 1896-1965

Home to the Belgian Workers Party, La Maison de Peuple was a magnificent political office, designed by the father of Art Nouveau, Victor Horta. Made of glass and steel, the structure could accommodate the needs of more than 300 people in its shops, meeting rooms, and cafes. A beautiful example of Victor Horta’s Art Nouveau genius, not often found outside private residences, La Maison de Peuple was the largest scale work of his architecture in Belgium. Unfortunately, by 1964 the building had fallen into disrepair and was condemned despite interest to save the structure. Though the building ultimately was demolished in 1965, the structure is arguably not fully lost architecture as numerous ornamentations live on throughout Belgium, and a recent research project has resulted in a 3D reconstruction of the facades and several interior rooms such as the stairwells, the auditorium, and the large brewery; which can be viewed at the Horta Museum in Brussels.

Church of the Archangel Michael, Warsaw: 1892-1923

Constructed during the reign of Czar Nicholas II in Russia, the Church of the Archangel Michael in Warsaw, Poland was the result of an expansion in church-building throughout the Russian empire. The Orthodox church, meant to serve the spiritual needs of Russian troops stationed in the region, was elaborate and magnificent, a nod to the elite worshippers it was created for. Built in the 1890s, it was destroyed only a couple of decades later – in 1925, as after the Russian troops left Poland in 1915 the church fell into disrepair and was destroyed as a symbol of the vestiges of Russian occupation.

Federal Coffee Palace, Melbourne: 1888-1973

Constructed in 1888 as a ‘temperance hotel’, with the mission of replacing the inhabitants’ love for alcohol with coffee, the Federal Coffee Palace in Melbourne, Australia ultimately caved to the changing of the times and acquired a liquor license after the temperance fad had run its course. With 370 bedrooms, the Federal Coffee Palace was built during Melbourne’s boom, and its grand facade including sculpted figures, a domed turret, and mansard roofs boldly proclaimed the successes of the city. Unfortunately, due to the building’s location on the warehouse-side of the central business district, demand flagged by the 1960s, and the building was sold to a developer in 1971 with plans to replace the structure with an office building. The Federal Coffee Palace regularly tops lists of the most regretful lost architecture in the city.

Relevant sources to learn more

Learn more about architecture with Sustainable Architecture: Between Ancient Materials and New Practices or Museum Architecture Today: Contemporary Spaces, Bold Design

Check out Stacker’s Iconic buildings that were demolished or The Guardian’s Sold for scrap: great city buildings that were stupidly demolished for more lost architecture