Articles and Features

Lucio Fontana: the Slashes on Canvas that Redefined How Art is Created

By Adam Hencz

“I do not want to make a painting; I want to open up space, create a new dimension, tie in the cosmos, as it endlessly expands beyond the confining plane of the picture.”

Lucio Fontana

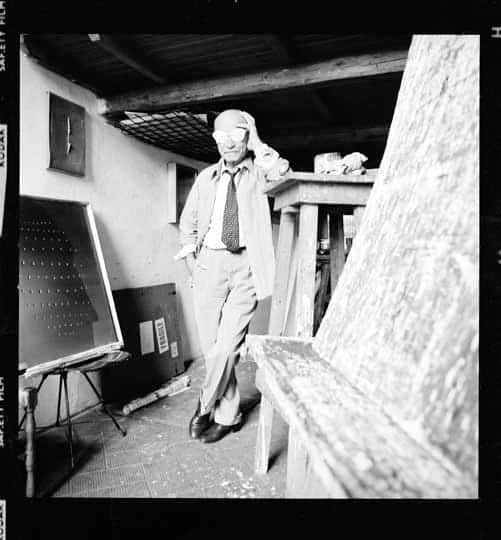

With his spatial concepts and his redefinition of specific materials and dimensions, Argentinian-Italian artist Lucio Fontana is regarded as the father of midcentury Spatialism, while his provocative practice channelled postwar innovation in a pioneering synthesis of art, technology, and science. Fontana gained international acclaim in the mid-1950s with his slash series, for which he cut into the canvas surfaces of monochrome paintings to provoke a sense of depth unachievable with paint alone. Though the canvases came to dominate his outward canon, Fontana was, however, also exhibiting immersive artworks around the world as early as 1949, nearly two decades before artists James Turrell and Yayoi Kusama first developed their first atmospheric experiments in the late 1960s.

A Life Between Two Worlds

Lucio Fontana was born in Argentina in 1899, to an Argentinian mother and an Italian father. He moved to Italy after his parents separated in 1905, and through his schooling, was exposed to the ideals of Futurism and new ways of creating art. He served as a second lieutenant in World War I, discharged with a silver medal after sustaining an arm injury. After he returned home, he resumed his studies, becoming a master builder, which laid the foundation for his first sculptures.

Escaping the political turmoil of Europe, Fontana moved back to Argentina in 1921 and began making busts for his father’s workshop, which specialised in making sculptures for graveyards. In 1926, he participated in the first exhibition of Nexus, a group of young Argentinian artists in Rosario de Santa Fé. On his return to Milan in 1928, Fontana enrolled at the Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, where he studied under Symbolist sculptor Adolfo Wildt. In Italy, he was gaining critical acclaim for his sculptures featuring abstract human forms and unusual materials, such as Homo Nero (1930), which he layered with tar. He also spent time in Paris and learning from artists such as Constantin Brancusi and Joan Miró.

The Foundations Of Spatialism

Fontana lived and worked in Milan until 1940 when he moved back to Argentina again when World War II broke out. He became a teacher and founding member of the Altamira cultural centre. As the professor of sculpting, he helped to promote the school’s philosophy that in light of recent scientific discoveries, a new art was necessary to reflect the modern world. He encouraged his students to embrace new conceptual approaches to creating art, urging them to forsake painting to make innovative art, for example projecting light. By formulating his ideas on artistic research, he defined a new kind of art and rejected old traditions that laid out the foundations of the movement he started in 1946, which became known as Spatialism.

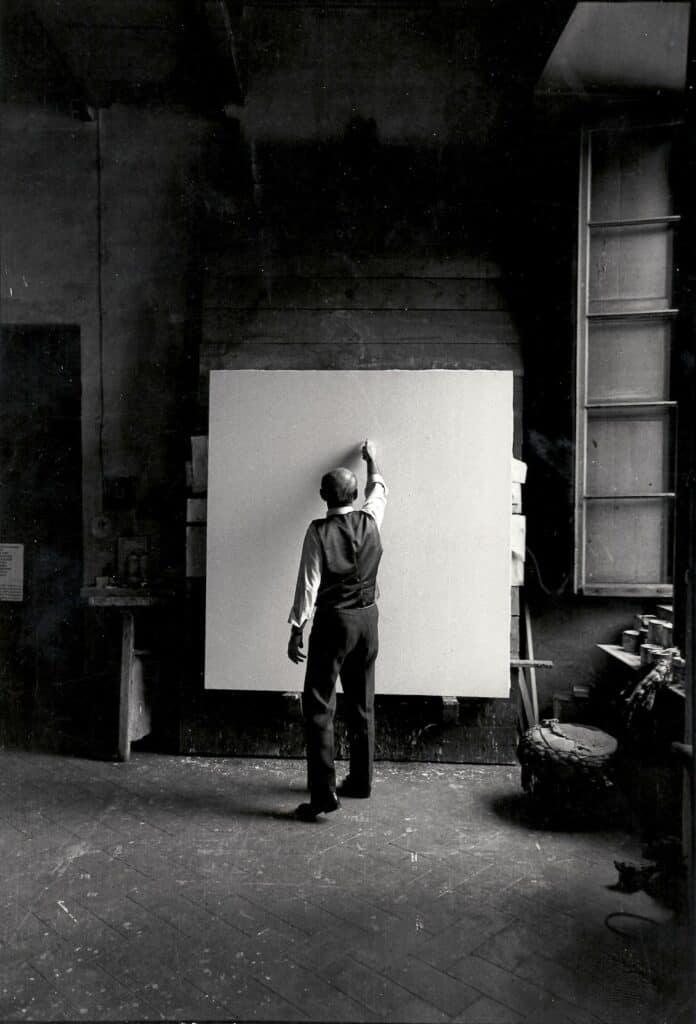

The main idea behind Spatialism was to create a form of art that would make a synthesis of sound, colour, movement and space in one single artwork. As he explained in Manifesto Blanco, his ultimate desire was to create a unity of art and space. “Colour, an element of space; sound, an element of time; and movement, unfolding in space and time,” Fontana wrote. Fontana was obsessed with the conceptual dimension of the art and perceived it as an instrument for research, rather than a mere matter of aesthetic. As he put it, “I do not want to make a painting; I want to open up space, create a new dimension, tie in the cosmos, as it endlessly expands beyond the confining plane of the picture.” He had called for an art that embraced science and technology and made use of icons of modernity such as neon light, radio and television.

“This idea of synthesis is grounded in the concept that certain scientific and philosophical developments have transformed the human psyche to such an extent that traditional “static” art forms and the differentiation of artistic disciplines have become obsolete. A new, synthetic art is advocated that will involve the dynamic principle of movement through time and space.”

Manifesto Blanco, 1946

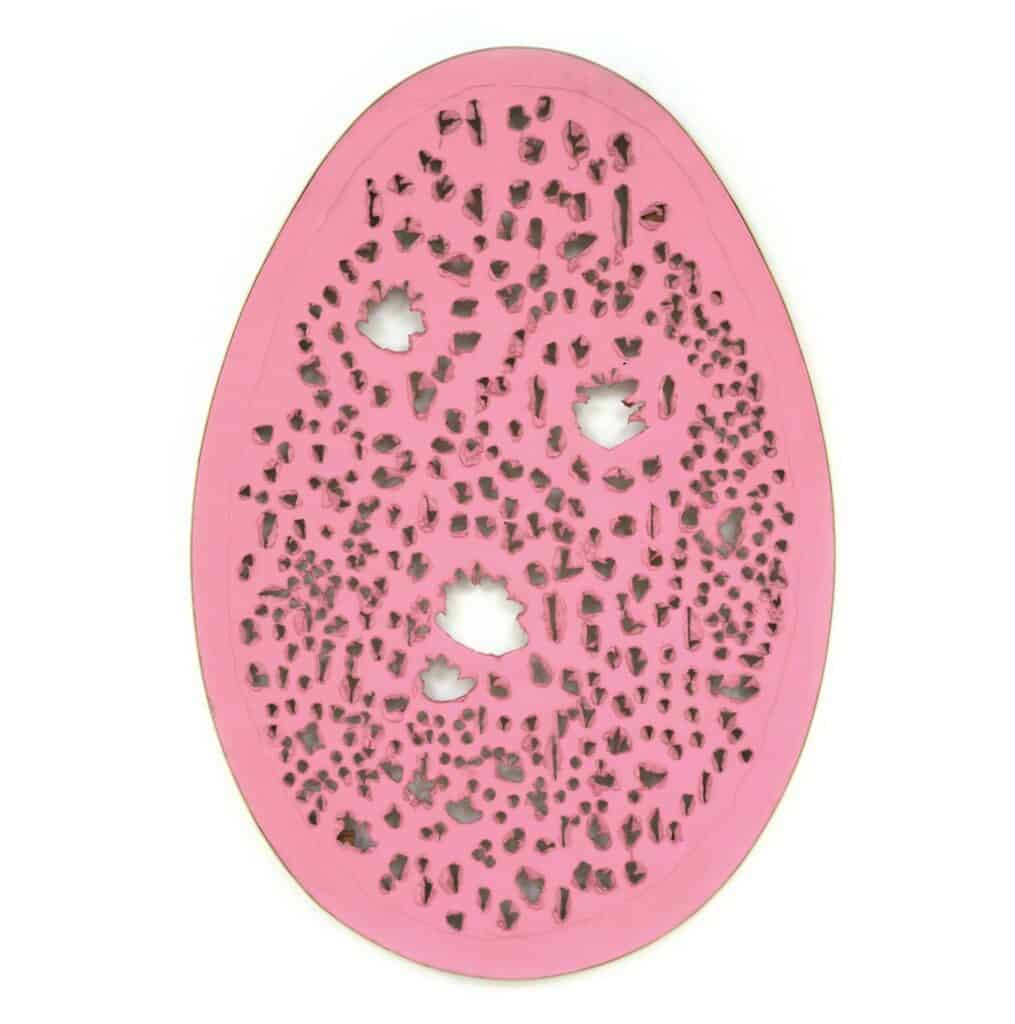

The year 1949 marked a turning point in Fontana’s career. He concurrently created his first series of paintings in which he punctured the canvas with buchi (holes), and his first spatial environment to be viewed in a dark room installed his Ambiente Spaziale at the Galleria del Naviglio in Milan. It consisted of a combination of abstract objects painted with phosphorescent paint lit by neon light and was a pioneering example of what became known as installation art. He subsequently went on to make the works on canvas to which he gave the generic title of Concetto Spaziale (spatial concept) although continuing to make installations using light.

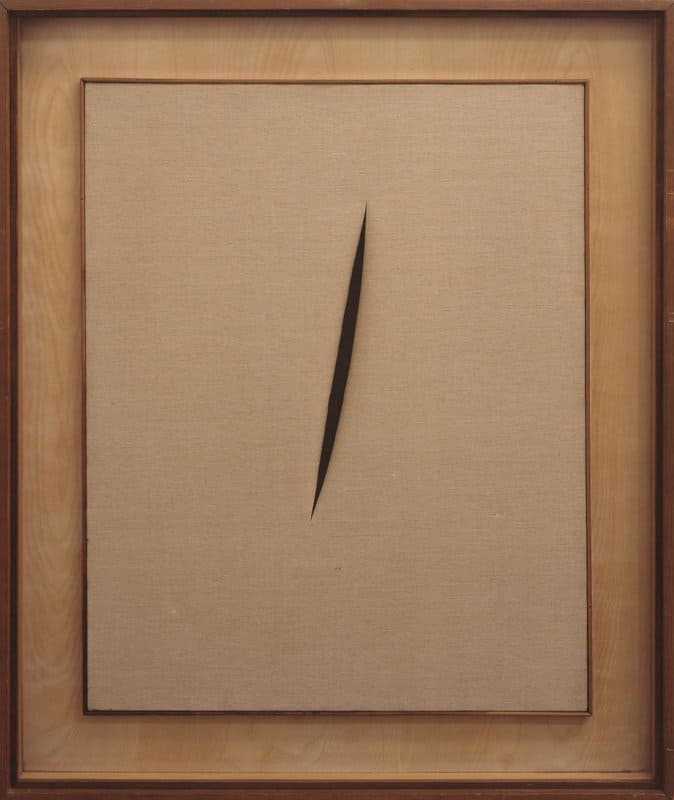

The basis of the Concetto Spaziale works was the piercing, or later slashing with a razor, of the canvas to create an actual dimension of space. Fontana made a long series of these and extended the idea into sculpture in his Concetto Spaziale, Natura series. Beginning in 1950, his tagli (cuts) series emerged as another Spatial Concept series. He stated that the series would “give the viewer the impression of spatial tranquility, of cosmic rigor, and of infinite serenity.” To achieve the tagli effect, Fontana would slash the fabric while the paint was wet, later giving the cuts more shape by hand, and using black gauze to fill the space behind the cut, implying the infinity of the space.

In the last year of his career, Fontana became increasingly interested in the staging of his work in the many exhibitions that honoured him worldwide, as well as in the idea of purity achieved in his last white canvases. These concerns were prominent at the 1966 Venice Biennale, for which he designed the environment for his work, and at the 1968 Documenta, Kassel, West Germany.

Relevant sources to learn more

Current group show at DIERKING, Zurich: Sign O’ the Times – Fontana, Goepfert, Verheyen

A New Kind Of Form. The Radically Reductive Sculptures of Brancusi

Art Movement: Zero Group

In Praise Of The Ellipse: A Tribute to Turi Simeti

Documenta 4 in 1968

Learn more about art movements:

Art Movement: Futurism

Art Movement: Symbolism

Spatialism on Tate.org