Articles and Features

Standards & Practices, Vol. 3:

Does Maurizio Cattelan know what he’s

responsible for?

William Pym

Standards & Practices

Comedian Dave Chappelle has a bit in his last standup special where he talks about being called to the Standards and Practices department of his cable network and being told to do things differently. He’s not too bothered about what the network thinks. There’s a vulgar, uproarious punchline. I like the idea of standards and practices. It makes for a good joke. The enforcer of arbitrary rules and norms, a person whose job it is to frame what’s right, right now. For how can you tame a moment? In the international art world, where I have worked since 2002, I grew to become very familiar with a world of amorality, grandiosity and arrogance. I watched pre-2008 hypercapitalism change everyone’s style, and watched money get darker. Now the art world is being rebuilt, like everything else, in the image of a new generation. And one thing is true now as it was then — the art world is a place of porous standards, and practice takes many forms. I am still here, somehow, and I am the Standards and Practices department.

The final major art world event of the 2010s occurred in Miami Beach at the beginning of December, when 59-year-old Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan taped a $120,000 banana to an outside wall of French gallerist Emmanual Perrotin’s booth at the Art Basel fair. You know this already, I’m certain, so let’s go a little further.

Thirteen years ago at the Frieze Art Fair in London, Cattelan and ascendant art-world power curators Ali Subotnick and Massimiliano Gioni, all close collaborators, used a Frieze London booth to restage Second Solution of Immortality: the Universe is Immobile by the Italian artist Gino De Dominicis. The original version of the work, a sculpture/performance in which a man with Down Syndrome stared at a rock, a rubber ball and an invisible cube, was shut down amid a now-somehow hazy hullabaloo after the first hour of the first day of the 1972 Venice Biennale. With no fanfare, Cattelan and crew presented it for the second time, in a 12-square-metre booth, this time featuring a British woman with Down syndrome. I wandered past her and it for two minutes at the brightly lit preview party; there was no indication from aura or attendance that it was the most important thing going on that night. It made the front page of the Art Newspaper and got a pop or two in the trades and the Guardian, but the work did not quicken pulses. There was neither praise nor great cultural correction, in fact there was no audible chatter at all. It was a curious result for a work that Claire Bishop, the leading academic of such things, had described as the most prominent postwar scandal in the history of the Venice Biennale. I was mostly drinking and zooming on girls back then, but I’d never seen anything like it, and I knew I’d never forget it.

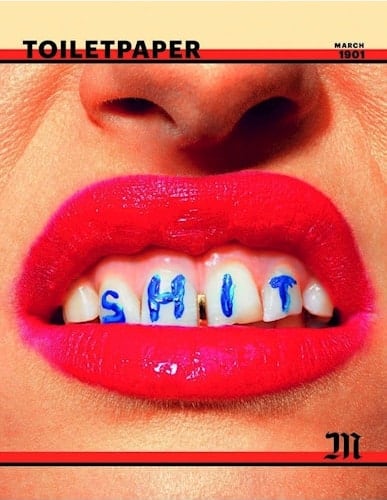

In 2010, Maurizio Cattelan and fashion photographer Pierpaolo Ferrari conceived TOILETPAPER, which is nominally a magazine but has always effectively functioned as a visual agency, producing imagery for editorial, products and the internet. The TOILETPAPER aesthetic anticipated, with astonishing acuity, many defining visual trends of the decade that would follow. Millennial pink and the aesthetics of decoration that came from it — the geometric soundstage of innocence where surfaces are sleek, colours soft, and nature ambiently present — appeared in protean form in TOILETPAPER. There is no commentary; the images are about feeling and charge alone. Cattelan and Ferrari fuse the carnality of French fetish god Guy Bourdin with everyday Surrealism and a Pop formalism that calls back to Carla Accardi and Colors magazine and the Memphis Group or, in other words, to the visual DNA of modern Italy. The TOILETPAPER look crafted an airless space that would through the 2010s become the space of social media, the stage where humanity predominantly presents itself to others. TOILETPAPER is very important to the last decade. It is casually visionary, a template for the textures that encapsulated the mysterious emotional brew of total intimacy and total distance, like sex without any fluids, that we settled upon once we committed to connecting primarily through our devices.

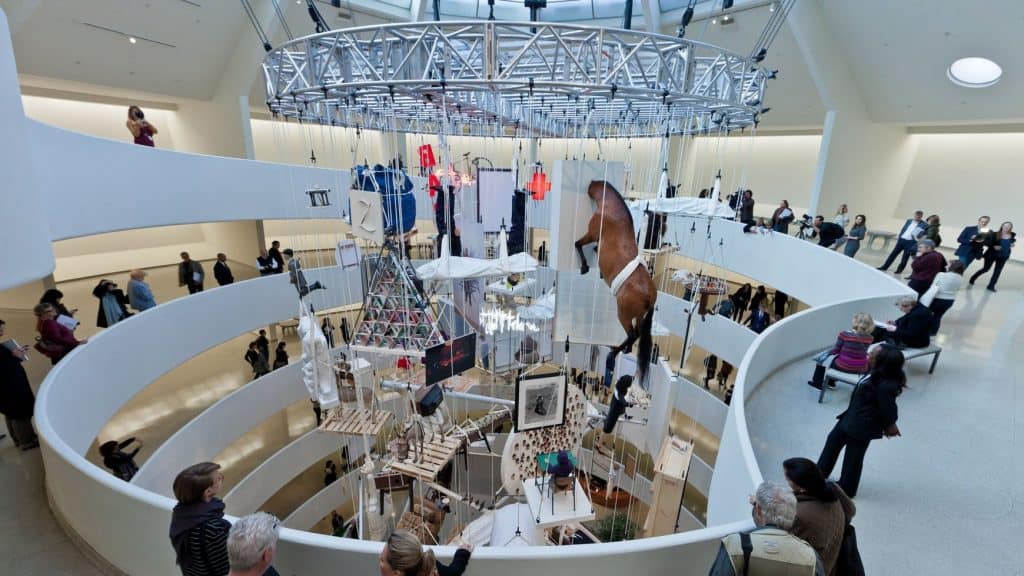

All this, then, is Cattelan’s special sauce. He is an artist who possesses a cultural clairvoyance, a natural ability to reach us and reflect us, while simultaneously challenging us and operating on an edge. Cattelan’s career began in a culture where it was paramount for art to ‘problematize’ — a modish verb of 1990s vintage about making art less passive and decorative — and his career now exists in a culture where ‘problematic’ concepts and people are emphatically, immediately starved of air. Cattelan has easily weathered this era of unimaginable change. His approach to problems has a euphoria to it; his enduring brilliance is an instinct for trusting what he knows about human beings and then, buoyed by those instincts, rolling the dice on everything working out perfectly. He has a touch, and when it does work out he is capable of instant art history. The decision to hang his 2011 career retrospective at the Guggenheim as a single giant mobile, an exquisitely rigged five-storey gallows of 130 works cascading through the core of Frank Lloyd Wright’s coil, is a cocktail-napkin idea — what if we don’t hang anything on the walls? — that managed to draw more attention to his artworks, their worth and our trust in them, as he pushed a single goofy idea to its absolute limit. Cattelan is an inspirer and a guide.

I reflected on Cattelan last month while working the floor in Miami, making connections and money even as I retreated from the crowd in my mind. His banana was taped to the wall on Wednesday morning, awaiting its audience. By Thursday morning, the second preview day of the fair, the work and its price tag were on the front page of the New York Post. No prizes for guessing that the headline splash was “BANANAS”. By Friday morning the work had become a selfie station, with a steady crowd clogging the aisle. By Saturday morning it was delirium. The crowd had congealed like fat in a pipe, impassable. People dug out banana gear from their closets, perhaps a Velvet Underground tee, perhaps a Swarovski crystal situation, very South Beach. A small group paraded with bananas taped to their cashmere, they were pleased with themselves. By Sunday morning the work had been taken down. Various people asked me where the banana was, which was fine. A lady gestured at a fruit sculpture, not a banana, and asked me “is this the banana”. This proved to be my breaking point.

We must only move our conversation forward. Emmanuel Perrotin described the experience as a “wonderful adventure”, but the adventure is over, just as the discussion is over. There’s nowhere for it to go. The banana worked, in that it could not have had a bigger impact, but it confirmed nothing beyond the most tedious clichés: the art world is silly and self-serving; money in the art world is absurd; people value spectacle and souvenirs above all else in an age where we must provide evidence of the quality of our existence to others. Cattelan, Subotnick and Gioni revived Gino De Dominicis’ work with the covenant that at some stage, if not now, we may elevate the conversation about disability and different types of perception. Provocation should be consequential. TOILETPAPER holds a mirror to us while introducing the slickest, most seductive versions of what we are and what we love. If you find yourself in the zeitgeist, elevate it, and make it even more ecstatic. The banana did neither of these things. The banana was a cosh, bonking discourse on the head and making it see stars and forget everything. How else would an adult point at a peach and ask me if it was a banana? We can’t afford art like this, which improves nothing, at this point in time. There’s too much at stake.

Relevant sources to learn more

Visit Perrotin Gallery Website

Visit the website of Art Basel

Read more about Maurizio Cattelan

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.1 : Barry Le Va

William Pym Standards & Practices, Vol.2 : Kalup Linzy