Articles & Features

The Most Outrageous Acts of Art Vandalism

“Is graffiti art or vandalism? That word has a lot of negative connotations and it alienates people, so no, I don’t like to use the word ‘art’ at all”.

Banksy

Although behind many art crimes, like thefts or forgeries, financial gain can easily be spotted as the primary incentive, things get complicated when it comes to art vandalism.

Usually, it has little to do with profit, instead most often involving a direct attack to message or materiality – for idealogical reasons or, sometimes, for no reason at all.

What really lies behind art vandalism? Is it the malicious intention to destroy or damage, or something else?

What Lies Behind Art Vandalism?

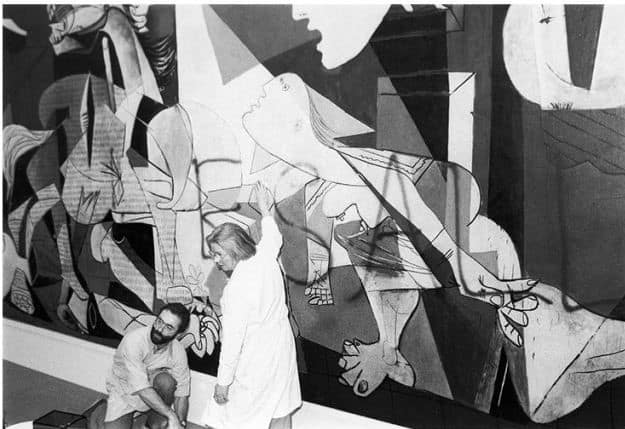

It is 1974, the afternoon of April 30th, when a man, in broad daylight, runs into the Museum of Modern Art in New York wielding a can of red spray and sprays the words “KILL LIES ALL” across Pablo Picasso’s anti-war masterpiece, Guernica.

When grabbed by the guards, to general astonishment, he shouts: “Call the curator. I am an artist.” Police came instead and took him away. The message seemed to be related to a protest against the Vietnam war, though immediately condemned and denounced as sacrilege by anti-war activists. Luckily the painting had a heavy varnish coating that acted as a barrier and protected the original paint layers; in less than an hour, the conservation team had washed the spray paint clean. The man, named Tony Shafrazi, is currently a successful art dealer and gallery owner in New York.

Vandalism has always appeared as a compelling and effective way for protesters to attract attention. This was also the case of the attack against the Rokeby Venus by Diego Velázquez, one of the most famous acts of defiance led by the women’s suffrage movement. In 1914, the day after the violent arrest of Emmeline Pankhurst, charismatic leader of the Women’s Social and Political Union, Mary Richardson – a militant suffragette herself – walked in the London National Gallery and slashed the Spanish masterpiece with a meat cleaver. Hers was no random choice, she had symbolically selected a painted epitome of female beauty: “I have tried to destroy the picture of the most beautiful woman in mythological history as a protest against the Government for destroying Mrs. Pankhurst, who is the most beautiful character in modern history. Justice is an element of beauty as much as colour and outline on canvas”.

However, there is not always a reason behind an act of vandalism, in many cases violent and unfortunate actions are due to the unpredictable behaviour caused by mental instability. The damage to Michelangelo‘s Pietà at the hands of Laszlo Toth is certainly among the best-known examples. The man, an Australian geologist, on 1972 Pentecost Sunday, jumped on the statue and started striking it with a hammer shouting “I am Jesus Christ; I have risen from the dead”. He managed to shatter the sculpture’s left arm and disfigure her face. The year before, he had also insistently demanded to meet the Pope, claiming to be recognized as the Messiah. Given his evident insanity, Toth was never charged with the crime but was committed to an Italian psychiatric hospital for two years, before deportation back to Australia.

Also unstable was Gerard Jan van Bladeren, the 31-year-old who, in 1986, attacked Who is afraid of Red, Yellow, and Blue III by Barnett Newman with a utility knife. The monumental painting features the primary colours with a strong emphasis on red. Its huge scale and powerful simplicity had already caused an intensely negative public reaction, to the extent that van Bladeren’s attack prompted many people to contact the Stedelijk – where the painting was formerly displayed – defending his actions, with a wag even suggesting Bladeren as a modern museum director. Unfortunately, the masterpiece’s misfortune was not over.

Almost five years later, the painting came back to the museum from the conservation studio of Daniel Goldreyer in Long Island; after the first sigh of relief, since the cuts were no longer visible, soon became clear that something was wrong: that deep shade of red that had previously made people so enraged had disappeared. It turned out from scientific analysis, that Goldreyer had rolled over the entire canvas with red house paint.

This intervention irrevocably ruined what was left of a masterpiece which has been defined twice-murdered.

But this incredible story, which has been the subject of the documentary titled The End of Fear, continues. In 1997, the vandal van Bladeren, knowing that the painting had returned to the museum, retraced his steps to finish what he had started and slash Who is afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue III once more. Since the painting was not on display, he found another piece by Newman, Cathedra, and attacked this one with a box cutter, then throwing pamphlets with blithering, incoherent writing. This time, van Bladeren was declared mentally ill and sent to a psychiatric institution.

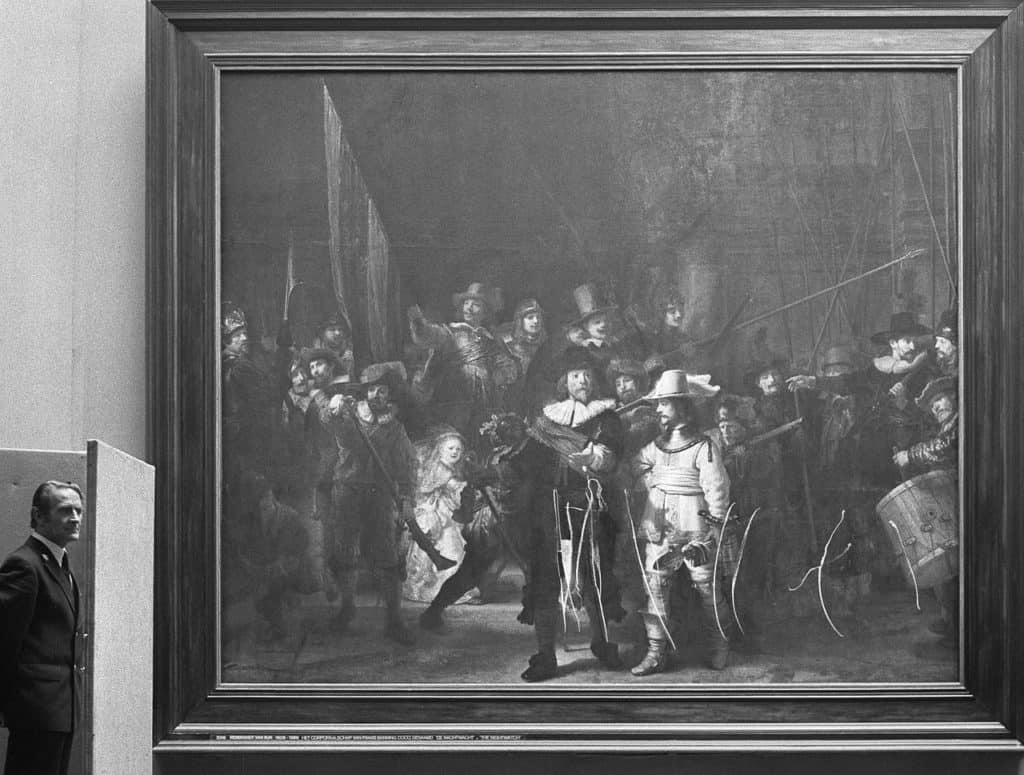

Some iconic artworks have become a repository of aggression even more than once. The Night Watch by Rembrandt has been attacked three times: by an unemployed Navy chef in 1911, then, in 1975, a former schoolteacher named William de Rijk, slashed the Flemish masterpiece claiming he was “doing it for the Lord” who “ordered him to do it”, and was later committed to a psychiatric institution. Again, in 1990, an escaped psychiatric patient sprayed the painting with acid. Last year, the Rijksmuseum has started a large and ultimate research and conservation project for The Night Watch, which is taking place in public inside a specially designed glass chamber.

The Mona Lisa as well, after the 1911 theft, has been vandalised four times. The last one occurred in 2009, when a Russian woman, disgruntled over having been denied French nationality, purchased a teacup in the gift shop and threw it at Leonardo’s masterpiece, fortunately without causing any damage.

Art Vandalism or Contemporary Art?

At times, there is a thin line between art and vandalism and it is controversial where to draw it. The case of Ai Weiwei is very illustrative in this regard. In 1995, the Chinese artist and activist used his personal antique collection to create the provocative work Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn, a series of three black and white photographs depicting him holding a 2000-year-old vase, then the vase in mid-air and, finally, the vase smashed on the floor. The piece, reflecting on themes long dear to the artist, such as our relationship with the past – with a special emphasis on Chinese history – heritage conservation as well as transformation and destruction, did not fail to shock the art world. While some saw the work as a sort of collaboration or handover over time, from the artist who manufactured the ancient vase to Ai Weiwei, many considered the voluntary dropping of such a valuable object extremely unethical, despite the artist being the object’s owner. Moreover, Ai Weiwei actually had to destroy two urns since the photographer failed to catch the first one shattering. Some others even supposed that the urn was a fake, refusing to believe that the artist had smashed an authentic vase.

At the beginning of 2014, the Pérez Art Museum in Miami, Florida, was hosting the exhibition “Ai Weiwei: According to What?”, a retrospective featuring the artist’s work of the last twenty years including a floor installation of sixteen ancient Chinese urns repainted in bright colours by Ai Weiwei; large prints of Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn hanging behind them. On Sunday 16th February, a man walked in the museum, picked up one of the painted vases and, despite a guard’s warnings, dropped it on purpose, smashing it into a hundred pieces right in front of the images depicting Ai Weiwei doing the same thing almost twenty years before. The man, named Maximo Caminero, was immediately arrested. He was acting in protest, claiming that the museum was not supporting the local art scene, giving too much space to top-notch international artists. His gesture did not mean to be a personal accusation against Ai Weiwei or his work, on the opposite, he had imitated his deeds in homage and solidarity. Still, both Ai Weiwei and the authorities did not seem to appreciate the gesture, and the man was charged with criminal mischief and forced to pay $10,000. It is surprising how small contextual nuances can lead similar acts to be perceived very differently.

Similarly, art and vandalism seem to be two sides of the same coin when it comes to street art. Without going into too much depth about the long-standing quarrel whether graffiti should be considered art or not, one just has to think of the case of Shepard Fairey. On the one hand, his iconic work is featured in prestigious institutions – the MoMA in New York, the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C., the Victoria and Albert Museum in London just to mention a few – on the other, the artist has been arrested around eighteen times for vandalism and destruction of property charges. In fact, rather than in a museum, you are most likely to have spotted one of his works in cities around the globe, maybe one among the myriad of Andre the Giant ‘OBEY’ stencils, or one of his large-scale murals covering once-bare walls.

Ironically, the same man who, by all accounts, is regarded as an outstanding artist, when acting without permission in public or private space, by the law is no any different from a teenager with a spray paint can. Conversely, without its free nature, a hint of unexpected, and a touch of criminality, street art would not be so powerful.

Things get even more paradoxical when is street art to be vandalised. Banksy knows that better than most. Whether it is to speak out about a specific topic, to criticise Banksy’s popularity, or simply to develop his work further, Banksy’s artworks are often subject to what could be recognised as vandalism even though incorporating existing graffiti is a common practice in the street art world. After all, we should assume is all part of the game and accept the transient nature of street art.

When, in 2007, London transport workers had painted over one of the most celebrated Banksy – a parody of Quentin Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction, with Samuel L. Jackson and John Travolta clutching bananas instead of guns – a spokesman stated: “the graffiti removal teams were staffed by professional cleaners, not professional art critics“.

Relevant sources to learn more

The End of Fear – Documentary

Follow the “Operation Nightwatch” online