A conversation with artist Raphael Brunk

By Ruth Polleit Riechert

Since Andreas Gursky ended his teaching activity at the Düsseldorfer Kunstakademie this year, Raphael Brunk is one of his last master students. With a unique technique, Raphael depicts virtual landscapes and architecture in high resolution photographs. In February 2017, Ruth met him for the first time, when he displayed two of his works at the Kunstakademie. Since then, she has followed his work process and has met him last month to discuss his art.

When and why did you start working as a photographer and artist?

I bought my first digital camera in January 2012 when I was still studying politics. Then everything evolved pretty fast. First, I started assisting a friend of mine who is a commercial photographer. At the end of 2012, I did my first free work, which finally ended up in my application portfolio for Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. There is no specific “why”, it’s just the way I can best express myself.

Your approach to photography is new. What exactly interests you and what is the technique behind your work?

I am primarily interested in all imaging processes, especially digital ones. When I have an idea, I begin to search for the technique that will get me there. Sometimes the method itself can be the idea. Then I try to find out what possibilities it offers me. For example, this could be a specially designed, digitally emulated camera that allows me to take gigapixel photos in computer games, or a five-euro scanner or a neuronal network that creates pictures for me.

Who or what inspires you? And what influence does Andreas Gursky have on your work?

I could never narrow it down to one single source of inspiration. Any sensory experience, be it digital or real, serves as a potentially inspirational moment. Since I was fortunate enough to study in a visual arts class, I was able to become acquainted with many different artistic approaches and perspectives, which undoubtedly influenced my work. Of course, I got some precious food for thought from my professor Andreas Gursky and also learned to leave my comfort zone and explore new avenues without ever losing faith in my work. I also consider his approach of questioning the image worthiness of any work to be extremely helpful.

Your work is very progressive. With Andreas Gursky, you talked a lot about the fact that in photography pretty much everything has already been done and there is nothing new anymore.

In the traditional sense, yes. Walking around with a camera to catalogue and archive industrial towers and what came later: Struth, the street scenes, all the architectural photography; that’s how I started. Those were basically my first steps into photography: the Becher-Schule. That’s precisely what I did. But my work was nothing new. They did not contribute to art history. I thought about that for a year. How can I tackle this while still work photographically? That’s when I started “to take photos” in a computer game.

Did you reprogram the computer games for that purpose?

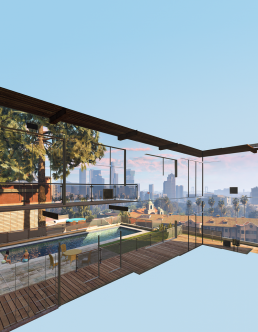

Three years ago, there was no software that could be used in computer games to generate images with a native resolution in the three-digit megapixel range, to go beyond a typical screenshot. My idea was: I want to take photos in computer games, but the work must have a certain quality in terms of sharpness and resolution, and it must be printable as very large formats without compromising the quality. Two of my friends who happen to be software developers “wrote” a camera we developed together: it’s a camera simulation. It works like a digital camera, and I can use it to shoot “ingame”.

And later you even reprogrammed computer games, so that the camera could take photos of things, that you usually don’t see in the game.

Exactly. We found a way to get into some kind of meta-level within the game, in which certain elements of the game structure are invisible. Therefore, the images look like architectural models or collages. For example, there is a lantern hovering somewhere, but it has no foundation. This is how the pictures in the “Captures” series were created. During the editing process, each image is rasterised into at least 400 individual image sections, which, based on a particular algorithm, are subsequently reassembled to become one picture.

I find the point very exciting at which you say you leave it to the computer. Is the result a random design?

The randomness only applies to a certain extent since I know roughly what the algorithm does. To say it’s pure coincidence is not correct. I would say that I use it as if somebody were painting blindly. Someone who has painted so much, that they could also paint while being blindfolded. In the end, they are still a little surprised when they open their eyes.

Is the chapter computer games finished for you?

There are around 40 works that have not been shown yet. And now and then I will include those in exhibitions. Fortunately, I always have this stock at my disposal. But for the moment, this is it. However, I can definitely envision myself working with the medium computer games again in some way.

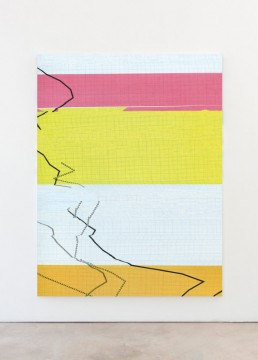

And what are you currently working on?

My new works are no longer about computer games. In principle, they are quite the opposite. The source material is books, some of which are around 50 years old. However, the translation of this material is digital again (scan), in combination with a manual, analogous gesture. In those works, there are, however, plenty of algorithms involved, decisions I leave to the computer. The works will later be printed on canvas.

What is the objective of your art? What do you want to express?

The fundamental interest is imaging. I am always interested in the medium and the question: how do I get there? For example, in computer games, the computer game world. Or as in the case of the scans: What happens during the translations from analogue to digital? But I can also imagine feeding a neuronal network with my works and inspirational imagery, which, in turn, produces works at a particular frequency. The options are diverse.

And do you also want to bring photography to the fore?

I’m interested in the search. I do not want to be so presumptuous and say: I want to bring photography to the fore. Photography in art is a very flexible term. I find exploring the limits exciting. Of course, software, technology, and data always play a role. And maybe I can expand the boundaries of photography through my continuous search; and maybe I actually did that on a small scale.

Thanks for the interview, Raphael!

Some of Raphael Brunk’s works can be seen in the current exhibition “Neu ist alles was ich habe” at Galerie am Meer in Düsseldorf as well as in the online exhibition “Raphael Brunk” at RPR ART (both until April 13, 2018). Some of the works shown have not yet been produced or published.

Text: Ruth Polleit Riechert

Photos: Jennifer Rumbach

Production: Christoph Blank