Articles and Features

Remembering Rondo, The Twin Cities’ Razed African-American Neighborhood

By Adam Hencz

Civil Rights and integration started in that little community. Most Americans don’t know that, and we want them to know where integration truly started.

— Melvin Smith

Rondo, a Twin Cities’ neighborhood, was the cultural center of the African American middle class living in the area, forming a tight-knit, integrated community with immigrants from all over Europe. After the heyday of the neighborhood from the 1930s through the 1950s, it was demolished by the construction of Interstate 94 during the 1960s. The Rondo series, the most recent body of work by artist couple Rose and Melvin Smith reimagines their years living in the neighborhood whilst also documenting their experience of the African American story and the broader history of civil rights that most often accompanies such narratives.

From the very beginning, Rondo was a haven for people of color and immigrants. The neighborhood was named after French Canadian Joseph Rondeau who sought refuge there from discrimination in the 1850s. In the following decades immigrants including German, Russian, Irish, Swedish, Norwegian and Jewish families found homes there. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) established its Minnesota chapter in Rondo, and Roy Wilkins, later leader of the national NAACP and a prominent figure of the Civil Rights Movement, was raised by an aunt and uncle in that very neighborhood. African American newspapers such as the Appeal, the Northwestern Bulletin, and the St. Paul Recorder were founded here, representing Rondo’s interests, which at the time were both reflective of and aligned with a wider civil rights agenda.

Music and theater flourished, integrated schools provided a relatively high level of education and even in the Jim Crow era people mixed quite freely, interracial dating and even marriage would take place. This openness drew in many African Americans migrating away from southern states, where they had faced the striking violence of intense racial prejudice. By the 1930s the neighborhood became the backbone and cultural center of the African American middle and working class with its vibrant social clubs, religious denominations and community centers.

The Oklahoma native Melvin Smith would go on to join the United States Marine Corps in Minnesota and later enrolled as a journalism student at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis-Saint Paul. Rose moved to Minnesota when she was seven and at that time was studying visual arts and taking studio art classes at the university to further her knowledge and practical skills. The two met in 1963 on a blind date and the couple became married almost immediately afterward. As Melvin remembers, he fell in love with Rose’s art first, but soon after fell for the woman who made it.

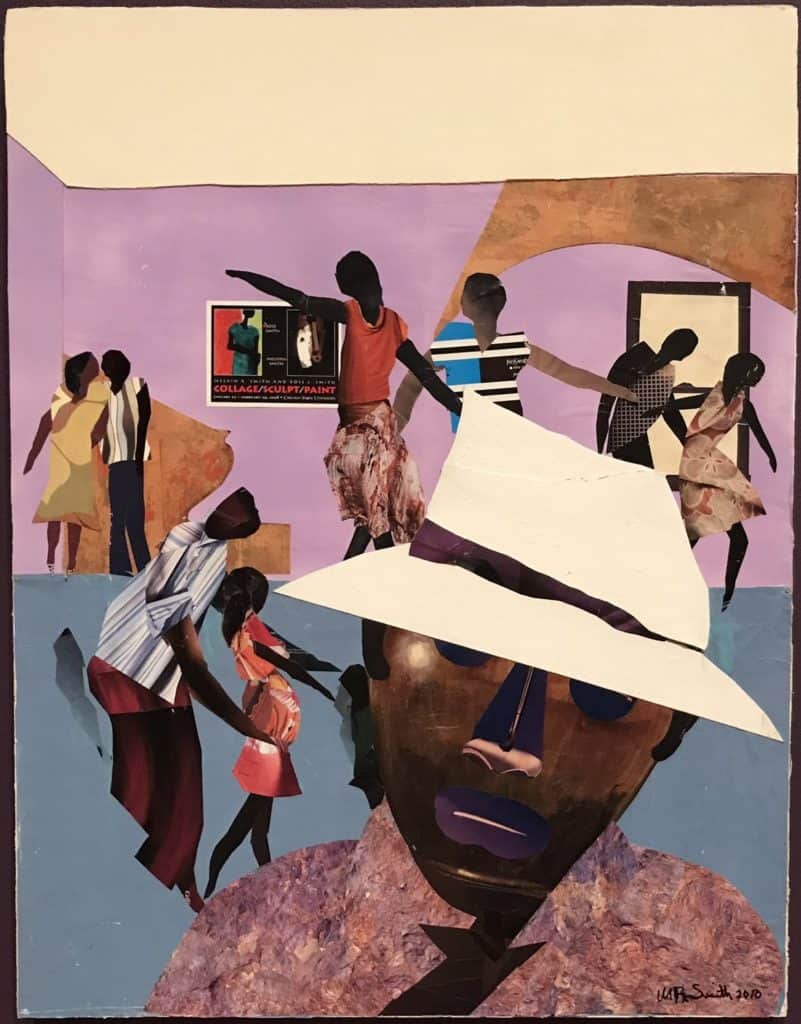

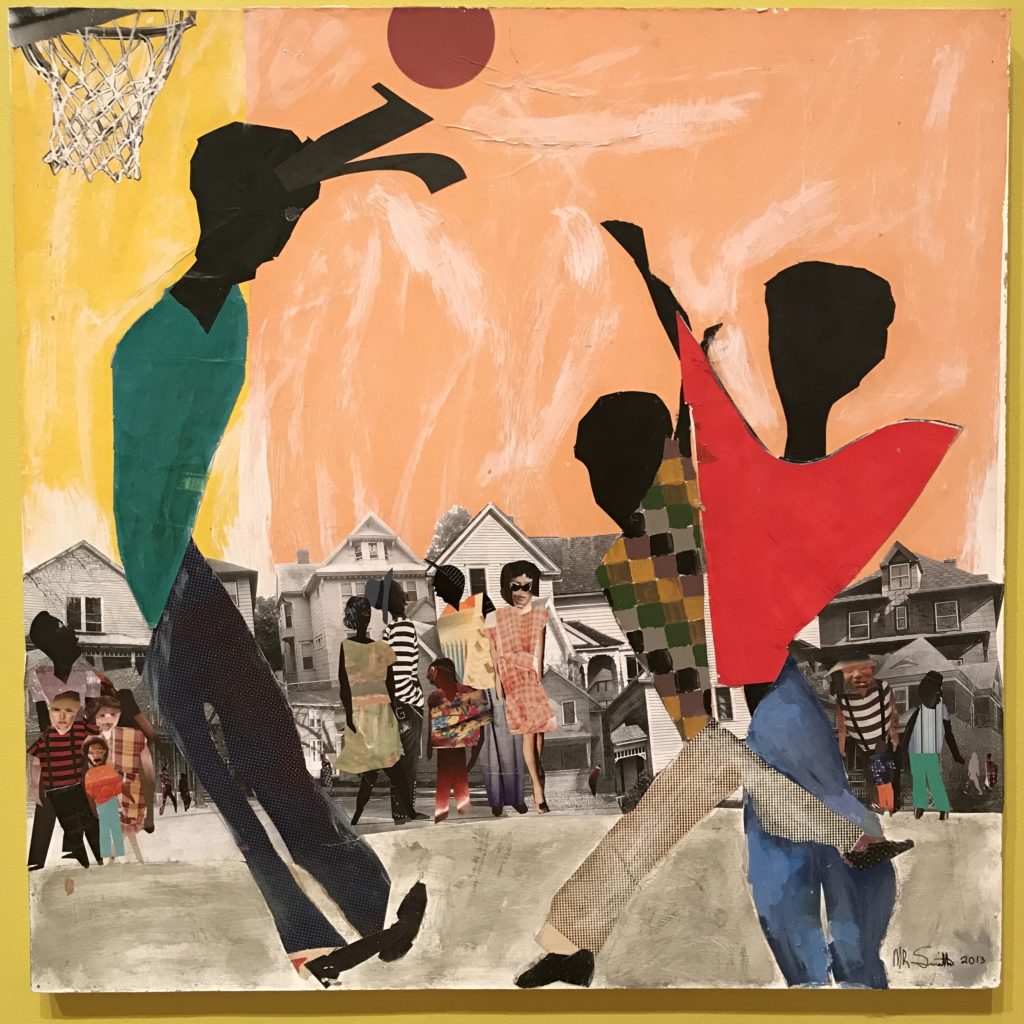

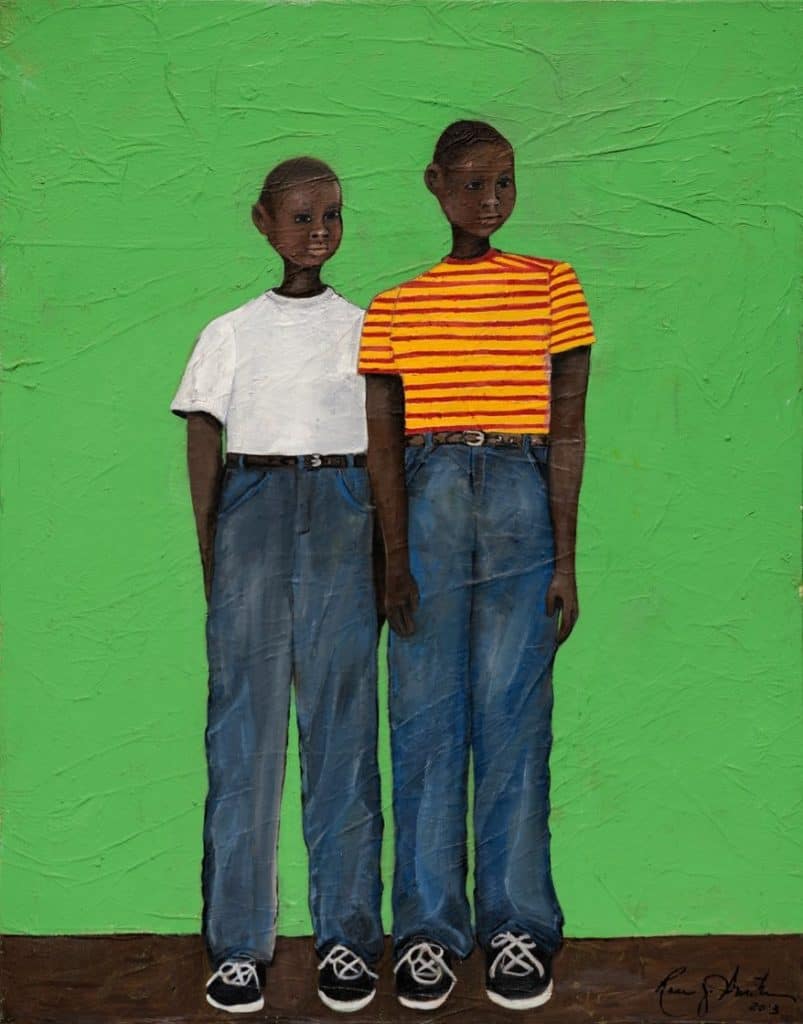

The artist’s works show the early Rondo, capturing the soul of the neighborhood’s once vibrant community; including its buildings, its people and their family and friends who were integral parts of that time and place. Melvin produces vibrant collage paintings and builds sculptures through the use of found objects, whereas Rose creates intimate and tranquil oil paintings. Their realist and expressionist pieces stem from the memories of their life in Rondo, and are reflections of what they have experienced in black communities throughout their travels.

Once the thriving neighborhood was torn apart by the construction of the Interstate 94 corridor, a highway that cut through the heart of the area, forcing hundreds of families to leave their homes, entrepreneurs to relocate and many businesses to permanently close. Despite the resistance of the residents, their land was taken by eminent domain. This executive governmental prerogative allowed the conversion of private property into public utility, but only if compensation to the property owners was provided. However, many Rondo residents rented their homes and therefore received no repayment or support for their relocation. Rondo was scattered and would never be the same.

After the demolition of Rondo, the couple traveled in search of like-minded individuals, and free expression of the kind of culture they had come to know, love and propagate. They spent time in African American renaissance communities such as New York City’s Harlem and Chicago’s Bronzeville, places that nurtured African American artist peers of the era like William H. Johnson, Jacob Lawrence and James Van Der Zee. Eventually in 1997 the couple arrived back in Melvin’s hometown where they founded and ran the Oklahoma Museum of African American Art for several years before returning to Minnesota, where they currently live.

The couple is deeply committed to sharing the largely unknown role of the Twin Cities in the larger history of civil rights. During the summer of 2019 the Weisman Art Museum in Minneapolis presented Remembering Rondo, an exhibition celebrating the lost neighborhood, and dedicated to the mission and work of the Smiths. The case of Rondo provides a stark example of how eminent domain disproportionately affected and disenfranchised entire communities, but is also an anthem for, as Roy Wilkins explains in his book Standing Fast, one of the first places where the peaceful integration became living proof of its possibilities.

Relevant sources to learn more

Why America Should Remember Rondo

Art Movement: Harlem Renaissance

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: James Van Der Zee