Articles & Features

Seeking The Whitest White: The Colour Feud Continues

“A great silence, like an impenetrable wall, shrouds its life from our understanding. White, therefore, has this harmony of silence, which works upon us negatively, like many pauses in music that break temporarily the melody. It is not a dead silence, but one pregnant with possibilities. White has the appeal of the nothingness that is before birth, of the world in the ice age.”

Wassily Kandinsky

Essential element of the artist’s palette, the colour white holds such varied connotations as to be contradictory. In Western cultures, it is associated with purity and innocence, spirituality, and peacefulness, while in many Eastern traditions, white represents sadness and death. It is arguably this highly-charged symbolic meaning that leads to consider white as a unique, perfect colour, although different nuances do exist – suffice is to say that the Inuit language has seven different words for seven different shades of white.

Artists know better than anyone and, throughout history, have experimented, made mistakes and breakthroughs in search of the purest, most immaculate, whitest white.

After centuries of continuous developments, recent scientific findings published in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science unveiled undiscovered levels of whiteness, opening up new vistas. Following the production of the blackest black and pinkest pink, the art world’s spotlight is now on the race for the whitest white.

A short history of white pigments

Conversely to what the strong connotation of this colour would suggest, not many white pigments exist; in fact, only two stand out as kings among the others: white lead and titanium white. Already known to the ancient Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, white lead dominated the scene for centuries by virtue of its warm undertone, opacity, and drying property.

No alternative could match the pigment’s brilliancy and unparalleled compatibility with oil painting, even in spite of its toxicity. The exposure to White lead, in fact, causes lead poisoning, a side effect so common among artists that has come to be known as the ‘painter’s colic’. For this reason, in the late 20th century its trade has been progressively restricted and widely banned.

The pigment has been mostly supplanted by titanium white. First mass-produced in 1916, this bright the compound has a higher refractive index than white lead – in other words, it is a whiter white – but also shows higher opacity and chemical stability.

In the 1940s, DuPont – one of the world’s largest manufacturers of the pigment – refined the production process developing a first-rate titanium white. Their product hit the headlines in 2014 when a technology consultant was convicted for economic espionage after stealing the company’s protocols and selling the trade secrets to China for US$ 28 million.

Recent developements: the whitest white

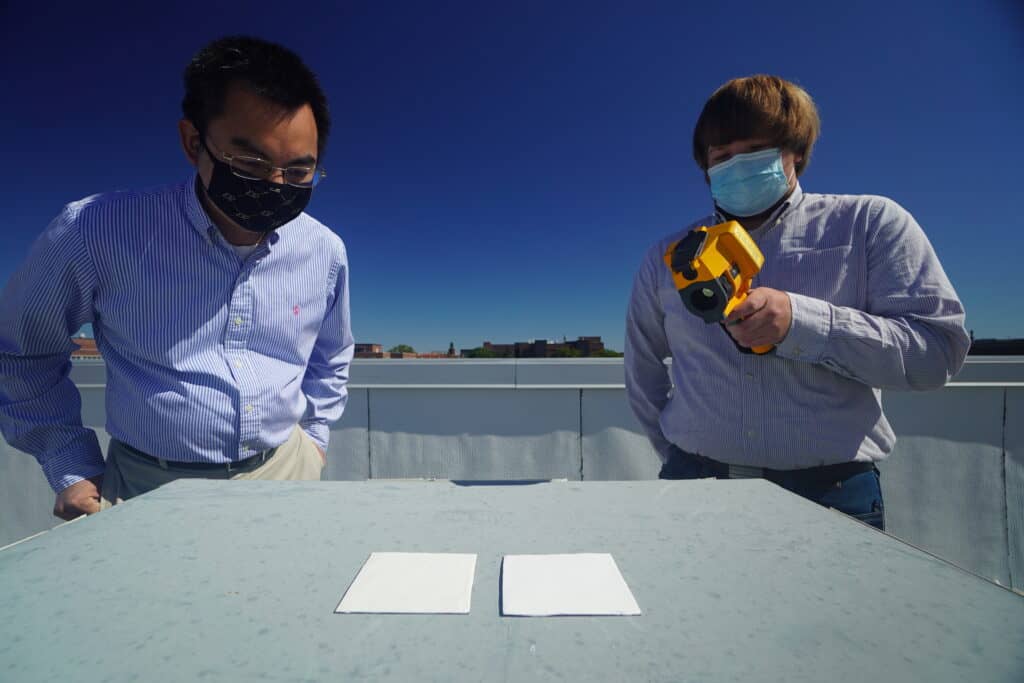

A few weeks ago, a team of engineers at Purdue University in Indiana has published the results of a six-year project unveiling an exceptional outcome: a new formulation of white acrylic paint made of calcium carbonate that efficiently reflects the 95.5 % of sunlight, achieving the status of whitest material ever produced. All white pigments act by scattering all wavelengths of light, but this incredibly high percentage also translates into a cooling effect: although indeed hard to envision, a surface coated in this paint proves to be cooler than its ambient surroundings – 18 degrees cooler, to be exact – even under direct sunlight.

This promising technology, also by reason of its affordability and compatibility with paint manufacturing processes, could serve an array of purposes, from preventing telecommunication equipment from overheating to lowering air conditioning costs and consequences by painting rooftops white; an application, the latter, with implicit beneficial effects in terms of sustainability.

To understand the scope of the potential benefits, one just has to consider that, from 2009 to 2018, New York City has painted more than 9.2 million square feet of rooftop white, and Los Angeles has spent $40,000 per mile to paint streets white. But besides the potential boon for industrial applications and the fight against global warming, the recent developments enter the arena of the art world’s war over coloured paint, a long-standing quest for the purest shades of colour that does not seem to be drawing to a close. On the contrary, the race for the whitest white has the hallmarks of the next chapter in the saga.

The colour feud continues

Let’s flash-back to 2016, when the award-winning sculptor Anish Kapoor secured exclusive rights to Vantablack, the then darkest material ever produced, sparking a rather frivolous yet entertaining controversy.

Opposing the idea that an individual artist could obtain such a unique licence, the artist and self-proclaimed champion of colours Stuart Semple took issue with Kapoor’s deal and launched a counterattack. First, he developed the pinkest pink, then the most glittery glitter, and ultimately produced an allegedly even darker paint named ‘Black 3.0’, banning Kapoor from purchasing it.

In September 2019, a third, unexpected – and likely definitive – super-black eclipsed the competitors, resulting from a collaborative project between the artist Diemut Strebe and MIT’s Necstlab. The bickering, however, is yet to be over. On the one hand, Anish Kapoor will debut a series of artworks covered in Vantablack at the Galléria dell’ Accademia during the next Venice Biennale – postponed to 2022. On the other, Stuart Semple is working on what he claims will be the ultimate whitest white. “I’m on a mission to make sure artists and creators get it first!”, he stated.

This is the Whitest White in the world – as long as you solemnly swear you are not a colour criminal, and aren’t associated with a colour criminal I’d love to send you some White 2.0 as part of our beta test: https://t.co/AfJ7ZwA2nG pic.twitter.com/COpR6CVvP8

— STUART SEMPLE (@stuartsemple) April 24, 2020

Following the industry’s interest in reproducing the structure of the whitest material in nature, the unusually bright scales of the so-called ‘Ghost Beetle’, Semple is currently testing a Beta version of paint in three different strains by means of a community-driven process. Anyone can buy it online, test it, and give feedback to the producer through a questionnaire…anyone except a string of supposed ‘colour criminals’. Anish Kapoor and Dupont, as expected, are at the top of the heap.

Although far from being developed with the creatives’ artistic needs in mind, the white acrylic paint produced by the team at Purdue University might have a major role to play in this rather petty feud of the art world; we will just have to wait and see.