Stepping into Max Ernst’s World at MoMA

By Charity Gardner

The thin, white-haired man stepped away from the painting and with a trembling hand set his paintbrush down. Before him, dark vines climbed the canvas, leaves clustered together in the shadows and behind them yellow light struggles to burst into the foreground. The painting is named La dernière forêt or in English “The last forest”. It is one of the last paintings that Max Ernst did before he passed away at the age of 84.

The Museum of Modern Art in New York currently has an exposition of Max Ernst’s art. One hundred pieces of his artwork, including paintings, collages and sculptures, give us a glimpse into his mind and life – a colorful, creative life.

Sixty-five Years of Artistic Brilliance

Born into the home of a German painter, Max Ernst developed a love for art at an early age. At the age of 18, he immersed himself in the history of art at the University of Bonn and one year later, began his artistic career. Over the next six decades, Max Ernst created paintings, collages and sculptures, as well as illustrated a few books.

Max Ernst experimented with a wide array of styles, techniques, and media. Young Ernst visited art exhibitions showcasing works by Pablo Picasso, Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin and as a result his first paintings carry many of the characteristics of Post-Impressionism, such as an emphasis on symbolism, abstract shapes and simple colors. A few years later after serving in the trenches during World War I, Ernst developed a lifelong interest in collages, as well as joined other artists in the Dada movement to protest war and nationalism.

In his mid-30s, Max Ernst explored surrealism and invented frottage, a technique where pencil and paper are used to make rubbings of different textures. He would then use these rubbings as the basis for a painting or other work of art. War again interrupted Ernst’s work in 1939. He spent several weeks in a French internment camp and then fled to the United States.

Settled in his new home, Ernst resumed painting and influenced the first American art movement that would gain international recognition: Abstract Expressionism. This movement popularized spontaneous and subconscious surrealist techniques, as well as intense emotions and defiance of artistic norms. All through his artistic career, Max Ernst created sculptures many of which were cast in bronze. Nine years before his death, he began experimenting with glass and created an exceptional chess set which he appropriately named Immortel.

MoMA introduces Max Ernst

Since September and continuing until the first day of 2018, the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York is hosting an exposition of Max Ernst’s works. This exposition allows both art experts and amateurs to step into Max Ernst’s world and view society through his eyes.

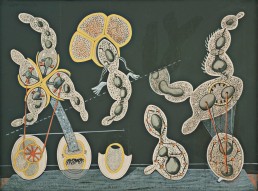

According to one of the curators, Anne Umland, the exhibition begins with La Bicicleta Gramínea, an overpainting that Ernst produced in the early 1920s. He began this painting with a pedagogical poster illustrating how brewer’s yeast cells mutate and reproduce. Ernst used black paint to cover over everything on the poster except the cells and then gave his creativity free rein. He painted a gray platform at the bottom of the painting to add depth, transformed the lower yeast cells into a bicycle complete with gears and bells and used the yeast cells in the middle of the poster to create imaginary creatures, one of which appears to be tightrope walking diagonally across the painting.

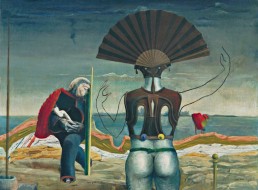

Another overpainting also being displayed is Weib, Greis and Blume (Woman, Old Man and Flower). Ernst created the oil painting which serves as the foundation for this work in 1923 and then sometime later, he transformed it into an overpainting by adding new elements. Ernst himself said that overpainting his own work gave it an “insaner effect” which he particularly loved.

MoMA’s Max Ernst: Beyond Painting exhibition also includes several sculptures which Ernst fashioned from bronze and painted stone, as well as a collection of 16 images that Ernst created from frottages or rubbings. Ernst employed a wide selection of materials, such as wooden boards, wire mesh, coils of twine and even crusts of bread, to make these rubbings. He then added details that turned these textured rubbings into natural beauties, such as a bird clinging to a tree trunk, a fragile dragonfly gliding towards the ground, a forbidding forest, as well as the human eye.

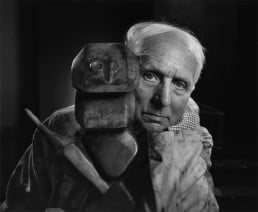

At some point during his artistic career, Max Ernst created a bird-like, hybrid creature which he considered his alter ego. He named the creature Loplop and included him in numerous of his works. You can see Loplop at the exposition in a collage that Ernst made to introduce the members of his surrealist group.

MoMA’s exhibition ends with a book entitled 65 Maximiliana that Ernst created with Iliazd, a book designer and publisher. They created this book to honor Ernst Wilhelm Tempel, a German astronomer who discovered a planetoid in 1861, and to express how they also wanted to represent domains outside ordinary human perception. Ernst provided much of the text in the book, as well as illustrations. He made the illustrations using aquatint techniques which involve etching the design onto copper or zinc plates which he then used to print the design onto paper. Iliazd made an invaluable contribution to their masterpiece by arranging the type to resemble constellations moving across the pages.

Get your free copy of Artland Magazine

More than 60 pages interviews with insightful collectors.