Articles & Features

Portraits of America: Grant Wood’s American Gothic

As we move into the full swing rollercoaster of election season, with candidates of both stripes seeking to convince the everyman, up and down and across the United States, that they are the best servers and custodians of the nation’s interests, we look at some iconic Twentieth Century artworks, considered, both at the time of their making and today, to be emblematic of American-ness. What that means depends largely on the work itself, and the manner in which the artist has chosen to represent their very own understanding of this notion. Sometimes satirical, often poignant, always compelling, Portraits of America shows us the many faces of a nation that, one way or another, is at the forefront of a global consciousness.

“We should fear Grant Wood. Every artist and every school of artists should be afraid of him, for his devastating satire”.

Gertrude Stein

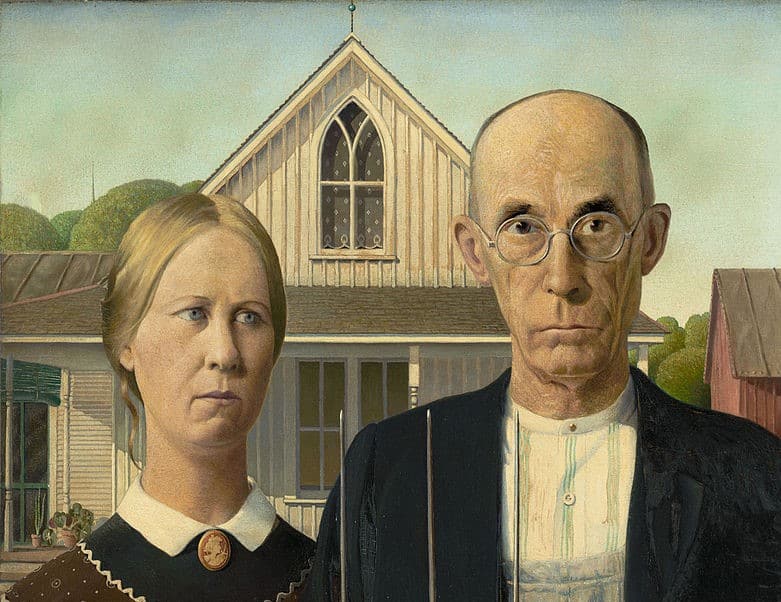

In 1930, when Grant Wood completed American Gothic and submitted the painting to the annual exhibition of American painting and sculpture at the Art Institute of Chicago, he was a shy and barely-known artist from Iowa, USA. He could have never imagined that he would win the Bronze Medal along with a substantial prize in cash. But, most of all, he could have never anticipated that his straightforward rural portrait would remain so embedded into American cultural consciousness that it came to be referred to as ‘America’s Mona Lisa’. Instantly recognisable by everyone, even if the name of its author remains obscure, American Gothic is counted among the most honoured, most captivating, and certainly most reproduced, artworks of all time, as well as the most parodied. Try to google ‘American Gothic parody’, and you will be astonished by its endless variations. But how and why has this intriguing picture achieved such a legendary status?

The artist: Grant Wood

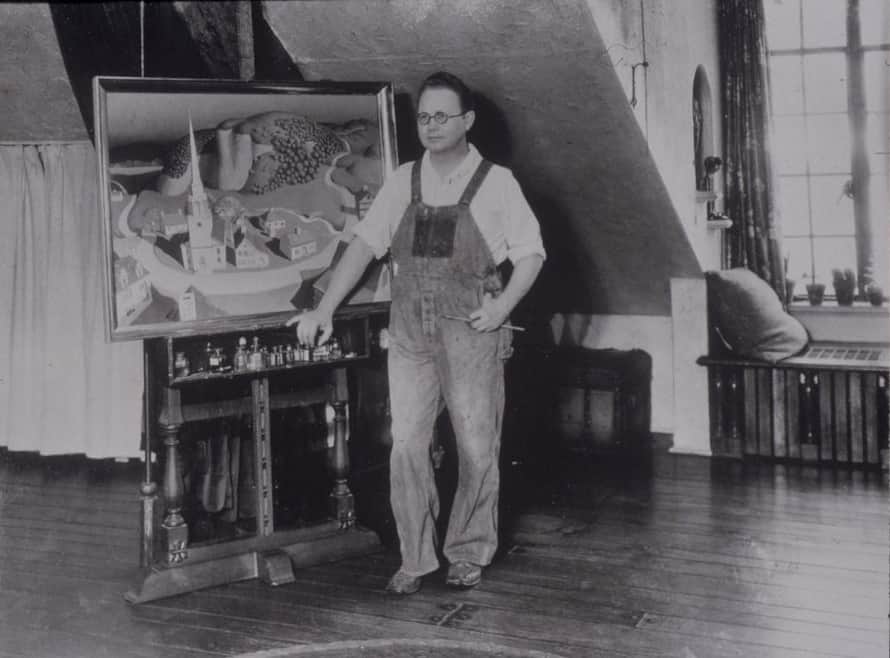

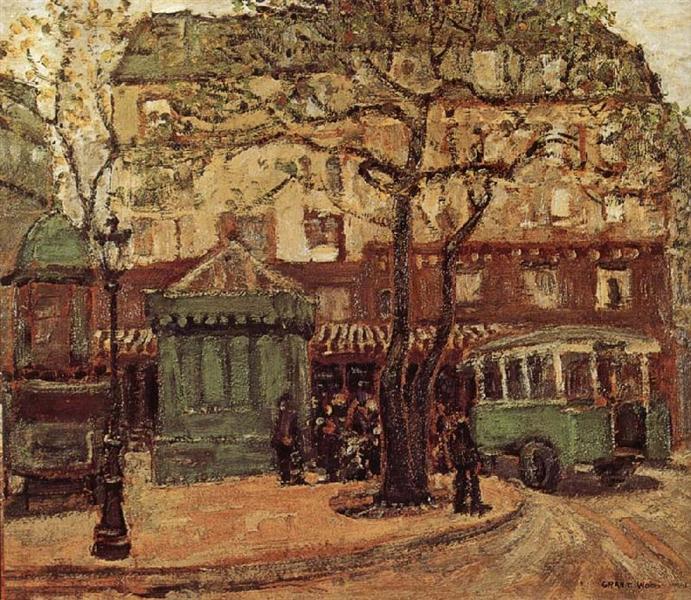

Grant Wood spent his childhood in the bucolic rural setting of his parents’ farm outside Anamosa, Iowa, and then in the small town of Cedar Rapids. He was a shy boy who enjoyed drawing in solitude, and his creativity soon developed in a precocious talent in a wide range of crafts, from silversmithing to ceramics and stained-glass design, which brought him to attend the Minneapolis School of Design and Handicraft. Nonetheless, it was a series of trips to Europe he made during the 1920s that exerted the greatest influence on his artistic training. In Paris, he studied life drawing at the Académie Julien and, whilst the most contemporary vanguard work of avant-garde Paris did not seem to catch his eye, he was fascinated by the delicate atmospheres of the relatively recent Impressionism and which immediately influenced his painting style.

It was in Munich, however, that he had a real epiphany. In 1928, visiting the Alte Pinakothek, he was impressed by New Objectivity paintings, but, above all, he was enthralled by the works of the Flemish Old Masters and their meticulous attention to detail.

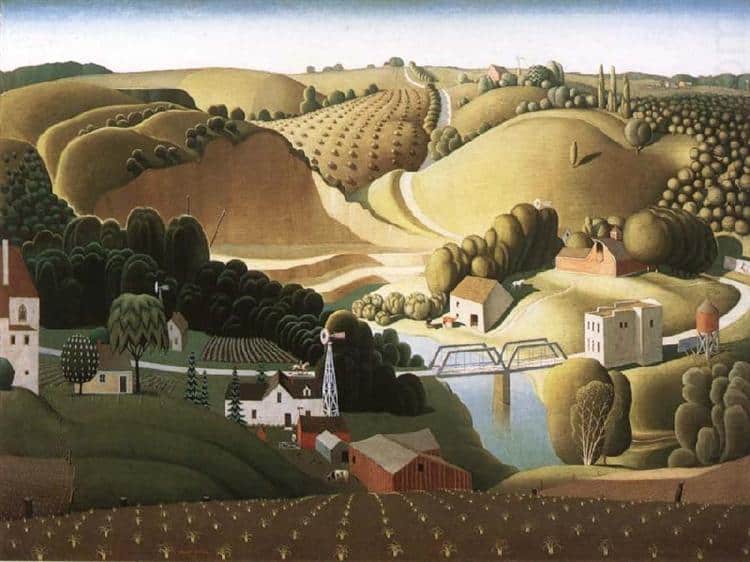

His style changed almost instantly and, once back in the USA, his adherence to this meticulous form of figurative realism fuelled the rise of a new mid-west American style known as Regionalism. In the struggle to forge a path for American modern art, Regionalist artists rejected European avant-garde in favour of a painting style that was, in their eyes, uniquely American in terms of both style and content.

The tendency towards abstraction introduced in the US by the seminal Armory Show established an opposition to realist representations of everyday rural life, but in the diversity of this burgeoning Contiental Superpower there was a place for reassuring images of a well-ordered world, especially in a time of struggle due to the onset of the Great Depression.

American Masterpiece

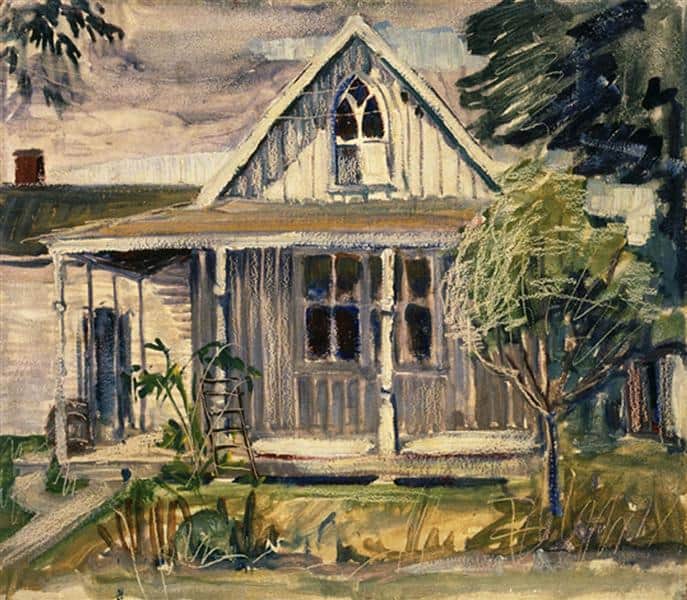

In August 1930, Wood was visiting the small town of Eldon, Iowa, when he accidentally spotted a rural house. It was a white cottage, no different to many farmhouses in the Midwest, however he was struck by a small and ostentatious detail, a Carpenter Gothic window on the second floor: “I saw a trim white cottage, with a trim white porch — a cottage built on severe Gothic lines. This gave me an idea. That idea was to find two people who, by their severely strait-laced characters, would fit into such a home. I looked about among the folks I knew around my hometown, Cedar Rapids, Iowa, but could find none among the farmers — for the cottage was to be a farmer’s home.“

Finally, he found two models in his sister Nan Wood Graham and his dentist Dr. Mc Keeby who reluctantly agreed to pose for what would become American Gothic.

A couple stands in front of the farmhouse and a red barn, with the pale blue sky in the background. They were originally intended to be a farmer and his wife, but rumour has it that Nan did not like the idea and insisted on being the farmer’s daughter instead. Dressed in a utilitarian collarless shirt under denim overalls and a black jacket, the man firmly holds a pitchfork in one hand, looking forwards with an impassive stoicism. The woman stands to his right, just behind his shoulder, wearing a dark colonial apron, her hair severely parted in the middle.

Both the rigid frontal arrangement and the minute details echo the works of the Flemish early Renaissance Masters – namely Van Eyck, Memling, and Dürer. Despite the fact that the architectural style of the window frame is usually believed to have given the painting its title, the term ‘gothic’ is also more than a nod to the fifteenth century painting style and, in a sense, the subject.

In a country inexorably on the path towards urbanisation and industrialisation, viewers might have perceived the two characters as belonging to a bygone age. To modern eyes, or certainly to the urban sensibilities of the coastal art observers and enthusiasts, the title of the work would also have implied a primitivism that the imagery itself evoked. Wood deliberately chose to adorn his models with old-fashioned elements such as the rickrack trim of the woman’s apron and the cameo brooch, which the painter borrowed from his mother’s wardrobe. He wanted to dress them as if they were “tintypes from my old family album”.

Upon closer inspection, the painting reveals technical complexity and considerable virtuosity. Every compositional element enhances the typically Gothic sense of verticality, from the characters’ elongated faces to three-pronged pitchfork. Complementary patterns recur multiple times: the print on the woman’s dress rhymes with the window drape, while the fork’s shape is both repeated in the stitching on the man’s overalls and the stripes of his shirt, as well as mirrored upside down in the two arches of the window. These compositional devices imbue the work with a homespun neatness; a kind of utilitarian, ‘God-fearing’ ordinariness that both satirises the mores of small town America, but also celebrates its very humility and hard working values.

Even though American Gothic is regarded as a key image of Regionalism, it is hard to find the comforting tranquillity of rural life in it. Indeed, there is no sign of the agrarian idyll in the two stern-looking characters, but rather a dark and ominous atmosphere emanates from the rigid couple who seem to be willing to defend their sacred home at all costs.

It is arguably this ambiguity that makes American Gothic so mesmerising.

American Gothic brought Wood unforeseen national success, and, following the 1930 exhibition, the Chicago Art Institute decided to acquire it for its prestigious collection. The painting never left the United States until 2016, when it travelled overseas to be displayed in two exhibitions featuring Depression Era art. They were The Age of Anxiety at the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris and America after the Fall at the Royal Academy of Arts in London.

“There is satire in it, but only as there is satire in any realistic statement. These are types of people I have known all my life. I tried to characterize them truthfully—to make them more like themselves than they were in actual life”.

Grant Wood

Multiple interpretations

According to the artist himself, he had conceived American Gothic as a celebration of rural American values, a quintessential portrait of ‘true’ Americans: solid people and hard-workers. However, seldom it was interpreted as he had intended. The first ones to show puzzlement were, in fact, Iowa farmers. When the picture appeared in the Cedar Rapids Gazette, Wood’s fellow countrymen and their wives deemed the painting as a spiteful caricature. The resentment was such that a woman threatened the artist, claiming that he should have his “head bashed in”.

Similarly, art critics such as Gertrude Stein and Christopher Morley interpreted the artwork as a biting satire against narrow-minded provincialism, the visual equivalent of the hit novel Main Street by Sinclair Lewis that ironically parodied small-town life.

Wood himself played the game and even inflamed the dispute with baffling statements. He used to disguise his sophisticated European artistic education by wearing denim overalls and proclaiming: “All the good ideas I’ve ever had came to me while I was milking a cow” – though he was no farmer at all.

Regardless of one’s interpretation, American Gothic undoubtedly captured a moment of transition and change, encapsulating an America in the grip of an overwhelming moment and struggling against drought, economic and social crisis, yet striving to find its own identity. It could not be more meaningful than it is today.

Relevant sources to learn more

Masterpiece Rental: My Life in the ‘American Gothic’ House

RA Podcast: the influences of American Gothic