Articles and Features

Stories of Iconic Artworks: Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square

By Shira Wolfe

“In 1913, trying desperately to liberate art from the ballast of the representational world, I sought refuge in the form of the square.”

Kazimir Malevich

Artland’s ‘Stories of Iconic Artworks’ series delves into the stories behind some of the most iconic works of art ever made. What were the conditions that contributed to the creation of the work, what was the artist experiencing at the time, and what was being transmitted? This week, we see what lies behind one of the most radical, famous works of art of the 20th century, Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square.

The Black Square: the Zero of Form

In 1915, Kazimir Malevich took a medium-sized canvas, painted it white around the edges, and filled the middle square with thick black paint. With this apparently simple act, Malevich became the author of the most impactful and terrifying work of art of the time. In his words, his Black Square reduced everything to the “zero of form.” It was his discovery and enactment of that critical point because of which and beyond which everything else ceases to exist, nothing can exist. Malevich, who was searching for the barest essentials of art in an almost mystical manner, considered the Black Square to be sacred: a symbol for a new, modern sort of spirituality.

Victory Over the Sun

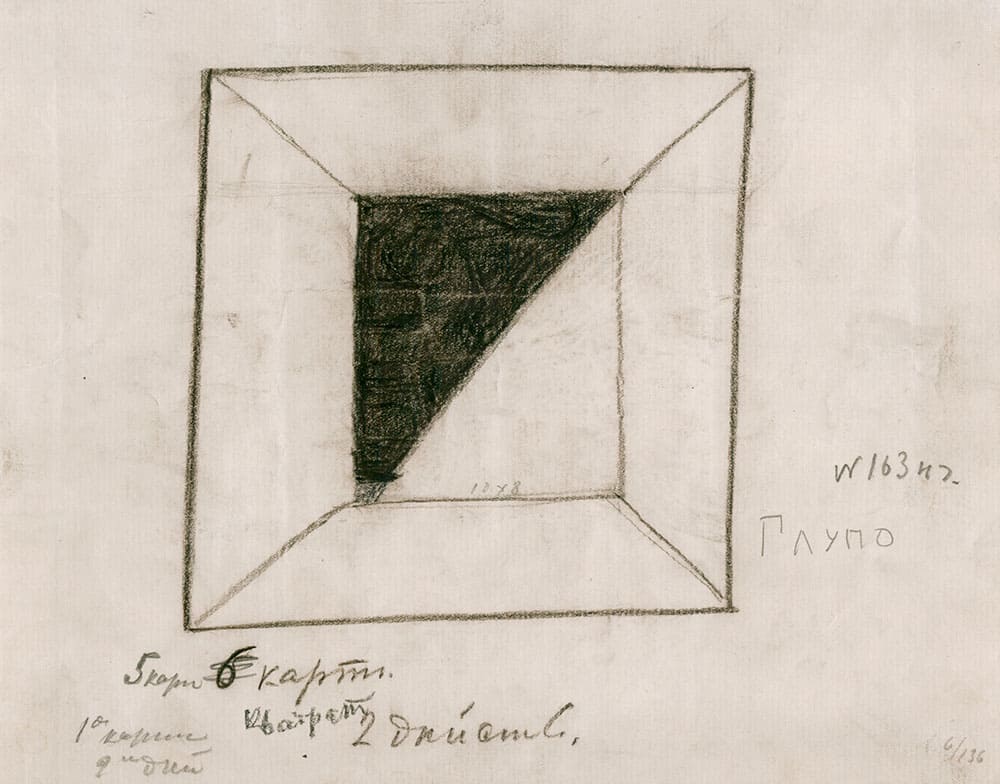

Before this iconoclastic Black Square, there was another black square. It appeared for the first time in Malevich’s 1913 scenic design for the Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun. A year or so before, Malevich and several of his friends and peers participated in the first All-Russian Congress of Futurists, held at a dacha north of St. Petersburg. There, the party decided to write an opera titled Victory Over the Sun. They commenced work then and there. Malevich created a set piece that was like a precursor to the Black Square: for Scene 5 of the 2nd “Doing” (the opera’s Acts were called “Doings”), he designed a curtain with the outline of a square. Malevich later saw this image as the first sign of his Black Square. Victory Over the Sun, in short, is about several strong men of the future (“Futurian Strongmen”) capturing the sun. In the opening scenes, the sun, which represents the decadent past, is torn from the sky, locked in a box, and given a funeral by these “Strongmen.” At the end of the play, they leave the world in total darkness, symbolizing a destruction of Russian tradition and making way for the future. While working on Victory Over the Sun, Malevich was still very much influenced by Cubo-Futurism. His work on this opera inspired him to move towards the new territory of Suprematism, extending from Futurism’s preoccupation with movement and Cubism’s reduced forms.

“Malevich quite consciously displayed a black hole in a sacred spot: he called this work of his “an icon of our times.” Instead of red, black (zero color); instead of a face, a hollow recess (zero lines); instead of an icon – that is, instead of a window into the heavens, into the light, into eternal life – gloom, a cellar, a trapdoor into the underworld, eternal darkness.”

Tatyana Tolstaya

Suprematism

According to Malevich, Suprematism was the “end and beginning where sensations are uncovered, where art emerges ‘as such.’” In this totally abstract art system, any sort of pictorial method that had been recognised in previous works of art was disregarded. Malevich believed the square to represent the absolute basic and purest of all art forms. Suprematist art was about capturing emotions, philosophical issues, and concepts, rather than depicting blatant subject matter. In a spiritual sense, Malevich believed that his two-dimensional form of art was a way for the human mind to ascend to a fourth dimension, to reach a celestial path.

The avant-garde poetry and literary criticism of the Russian Formalists played an important role in Malevich’s development of Suprematism. The Russian Formalists saw language not merely as a transparent means of communication. For them, there were only delicate links between words, signs, and objects. Words could create fresh, strange perspectives on the world. Suprematism had a similar aim: by removing the representational symbols of the real world, they offered the viewer a contemplation of the world through abstracted art completely stripped to its core.

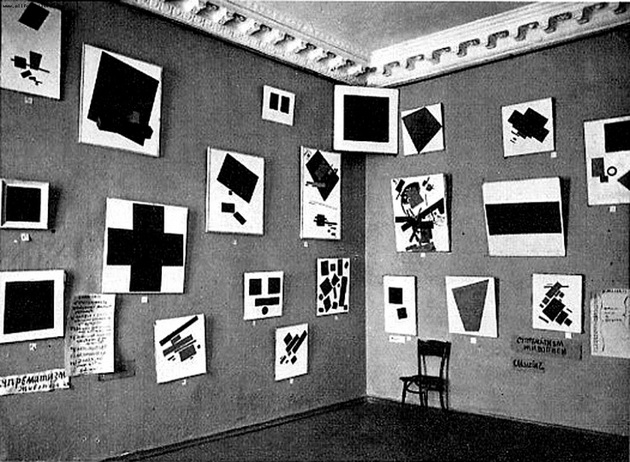

Malevich was joined in 1915 by fellow artists Kseniya Boguslavskaya, Ivan Klyun, Mikhail Menkov, Ivan Puni and Olga Rozanova to form the Suprematist group. Their first exhibition was titled The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10 (1915-1916). Malevich, who took a great deal of inspiration from the Russian Orthodox Church, hung his Black Square in the most sacred spot in the room.

The First Exhibition of the Black Square

The sacred spot where Malevich chose to hang his Black Square is known in Russia as “the beautiful corner” or “the red corner.” It is the point where the wall meets the ceiling, which is usually reserved for religious icons. With this provocative move, placing his Black Square in this religious spot, Malevich drew attention to what he considered to be the most important work of art in the exhibition, imbued it with transcendent power, and subverted tradition.

In the words of Russian author and critic Tatyana Tolstaya in her The New Yorker essay “The Square”: “Malevich quite consciously displayed a black hole in a sacred spot: he called this work of his “an icon of our times.” Instead of red, black (zero color); instead of a face, a hollow recess (zero lines); instead of an icon – that is, instead of a window into the heavens, into the light, into eternal life – gloom, a cellar, a trapdoor into the underworld, eternal darkness.”

In the manifesto published in concurrence with the exhibition, From Cubism and Futurist to Suprematism in Art, Malevich claimed to have transcended the boundaries of reality and to have crossed over into a new type of awareness. After The Last Futurist Exhibition of Painting 0.10, Malevich’s black square set against a white background became the symbol of Suprematist art. The work was a turning point in Russian avant-garde art. A turning point from which there seemed to be no turning back.

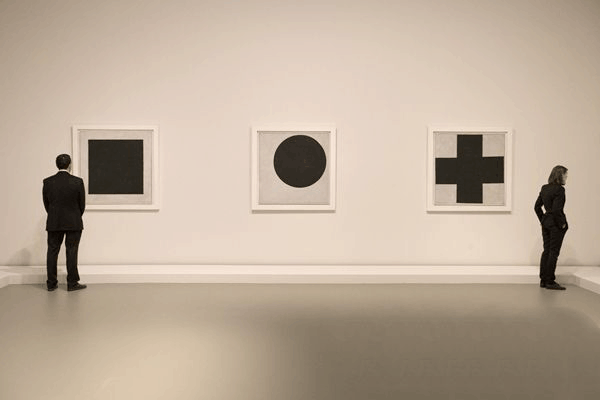

The Other Black Squares

All in all, Malevich painted four black squares (not counting his first exploration of the form and theme during his scenic design for Victory Over the Sun.) After his first Black Square from 1915, Malevich painted the second black square around 1923 as part of a triptych including a black circle and a black cross. He executed the work together with his closest disciples Anna Leporskaya, Konstantin Rozhdestvensky and Nikolay Suyetin. His third black square was probably painted in 1929 for Malevich’s one-man show, due to the poor condition of his original Black Square from 1915. The fourth black square is the smallest, and is thought to have been painted in the late ’20s or early ‘30s. It is said that this painting was carried behind Malevich’s coffin on the day of his funeral.

X-ray Analysis of the Black Square

In 2015, x-ray analysis done by experts at Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery revealed two previously done paintings, as well as an inscription, underneath the 1915 Black Square. The initial image is a Cubo-Futurist composition, while the painting directly underneath Black Square is a more colourful proto-Suprematist composition – the colours can be clearly seen through the cracks of the Black Square. A handwritten note by Malevich on the painting’s white border was also uncovered. The text reads: “Negroes battling in a cave,” and most likely refers to an 1897 painting of a black square by the French satirist Alphonse Allais titled “Negroes Fighting in a Cellar at Night.” This adds a surprising twist to the story of the Black Square, as it not only reveals a distasteful racist joke, but also means that Malevich’s initial formal ideas for this iconic work might have come as a response to or interpretation of Allais’s work.

Impact and Response

Whatever the different influences, inspirations and driving factors were behind Malevich’s creation of this work of art, its impact on art and society cannot be understated. At the time of the first exhibition of the Black Square, it shocked and moved many people, and it influenced countless artists for generations to come. Alexandre Benois, an artist and contemporary of Malevich’s, said of the Black Square:

“This black square in a white frame – this is not a simple joke, not a simple dare, not a simple little episode which happened at the house at the Field of Mars. Rather, it’s an act of self-assertion of that entity called ‘the abomination of desolation,’ which boasts that through pride, through arrogance, through trampling of all that is loving and gentle it will lead all beings to death.”

For many, the Black Square is a mystical, powerful work which represents the zero point in art, and heralded the break between representational and abstract painting. For others, like for Tatyana Tolstaya, it is deeply problematic because she believes it paved the way for art that is based on desacralisation, inherent meaninglessness and the shock factor.

Returning once again to Malevich himself, the artist found refuge in the form of the square in an attempt to free art from the weight of the representational world. In his words: “The square is not a subconscious form. It is the creation of intuitive reason. The face of the new art. The square is a living, regal infant. The first step of pure creation in art.”

Relevant sources to learn more

Artland Art Movement: Suprematism

For more information about Kazimir Malevich and the Black Square: