“On February 25 1970, nine paintings by Rothko arrived at the Tate Gallery. A few hours earlier, Rothko’s body was discovered dead in his New York studio.” – Simon Schama

All works of art carry a very specific, personal story about how they came to be. Artland’s Stories of Iconic Artworks series delves into the stories behind some of the most iconic works of art ever made. What were the conditions that contributed to the creation of the work, what was the artist experiencing at the time, and what was being transmitted? Our first article in the series explores the story behind Mark Rothko’s Seagram Murals, which today hang in a special room in the Tate Modern.

Mark Rothko was an intensely troubled artist with a flair for the dramatic. Did he count on the arrival of his paintings at the very time of his suicide? We will never know. Nevertheless, the symbolism of the two events is striking. The nine murals were created as a series, commissioned by the Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram Building in Manhattan. Rothko created them at the height of his career as a painter, when he was one of the most successful Abstract Expressionist painters in New York. The fact that Rothko accepted the commission in the first place is puzzling. He was revolted by capitalist America, and felt disdain towards anyone who contributed to it – and the Four Seasons Restaurant, in New York’s swankiest skyscraper, was destined to become the very epitome of America’s capitalism.

Mark Rothko and the Seagram Commission

In the spring of 1958, Philip Johnson approached Mark Rothko about creating a series of paintings for the smallest of two dining rooms at the Four Seasons Restaurant on the ground floor of the Seagram Building. Mies van der Rohe, the former leader of the Bauhaus, was the architect selected to design the building. With Johnson’s assistance, he created an elegant, expensive office tower, the crowning glory for Samuel Bronfman, the man who had started the Canadian Seagram liquor business. Johnson and Rothko agreed that Rothko would supply 500 to 600 square feet of paintings for 35,000 dollars.

It was the first time that Rothko would paint a properly unified series. “I believe he actually felt that he had gone as far as he could in painting until the proposal for the Seagram Building murals was presented to him. It absolutely supplied him with a whole new dimension,” said Rothko’s assistant Dan Rice. Rothko’s close friend Dore Ashton emphasises this by saying that Rothko’s desire to become immersed in the spaces of his paintings became increasingly domineering “until it occurred to him that the most satisfying means would be the most literal: that canvases would surround the viewer as murals. Fortunately the opportunity to move into the larger scheme –what he called the ‘jointed scheme’ – arrived in the form of an invitation by Philip Johnson to paint murals for the Four Seasons Restaurant in the Seagram Building.” Still, Rothko felt ambivalent about the commission, and had a contract drawn up which would allow him to back out of the deal and retrieve his paintings if necessary. He was obviously torn between his hatred for the wealth and greed of capitalism and his desire to create his own special place for his art.

Rothko’s Working Process

Shortly after accepting the commission, Rothko rented an old YMCA gymnasium at 222 Bowery and set to work. He usually arrived around 08:30 or 09:00 and would work for hours, sometimes even days, on end. He worked on the project for about two years, and created three sets of murals, each set changing colour and becoming increasingly darker. Starting out with orange and brown, he concluded with deep maroon and black A year after he had started painting, Rothko visited Europe with his wife Mell and daughter Kate to take a break from his hard work, and explore the creative realms of his fellow artists. In the ship’s tourist class bar, Rothko approached John Fischer, in need of a conversational partner. “So far I’ve painted three sets of panels for this Seagram Job,” Rothko said. “The first one didn’t turn out right, so I sold the panels separately as individual paintings. The second time I got the basic idea, but began to modify it as I went along – because, I guess, I was afraid of being too stark. When I realized my mistake, I started again, and this time I’m holding tight to the original conception”. By this time, Rothko had already started to lose faith in the Seagram commission. Disillusioned, he told Fischer: “I accepted this assignment as a challenge, with strictly malicious intentions. I hope to paint something that will ruin the appetite of every son of a bitch who ever eats in that room.”

Inspirations

His trip to Europe did, however, prove inspiring and refreshing. For one thing, he revisited old sites of inspiration. While working on the Seagram Murals, Rothko had started to realise just how much Michelangelo had inspired him. “After I had been at work for some time, I realized that I was much influenced subconsciously by Michelangelo’s walls in the staircase room of the Medicean Library in Florence. He achieved just the kind of feeling I’m after – he makes the viewers feel that they are trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up, so that all they can do is butt their heads forever against the wall,” said Rothko. Rothko had a chance to visit this staircase room during his trip.

“Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine.” – Mark Rothko

Rothko Withdraws from the Commission

Shortly after returning from his travels, Rothko decided to have a meal at the Four Seasons restaurant with his wife to take in the space that was to house his murals. The extravagant surroundings combined with the luxurious courses proved too much for him. That very evening, he called his friend and art advisor Katherine Kuh and told her he was returning the 35,000 dollars and claiming back his paintings. He famously stated: “Anybody who will eat that kind of food for those kind of prices will never look at a painting of mine.”

According to a sketch made by Dan Rice, it seems that seven paintings were to grace the walls of the dining room; three on the east wall, three on the west wall, and one on the south wall. Still, we can only speculate, since Rothko constantly changed the composition of his murals. He likely would have continued to change his mind about which murals were to be used during their placing in the restaurant.

A New Life: The Seagram Murals at the Tate

After he withdrew from the commission, Rothko kept the paintings in his studio, where he would show them to visitors from time to time. In 1965, the director of the Tate Gallery, Sir Norman Reid, approached Rothko with a proposition for a special Rothko Room in the Tate Gallery. Reid suggested that Rothko give a representative group of paintings, but Rothko instead chose to give a group of the Seagram Murals. He must have recognised Reid’s proposal as the perfect opportunity to give his series of murals the private “place” they were supposed to have had all along.

In 1969, after years of negotiating, Rothko donated nine of his murals, a series of maroon and grey paintings, to the Tate Gallery in London. The paintings have adorned the rooms of different Tate galleries throughout the years: they have moved rooms in the Tate Gallery, stayed at the Tate Liverpool, and finally found their place at the Tate Modern in London, where a 2008-2009 exhibition reunited them with seven of their relations from the Kawamura Museum of Modern Art in Japan.

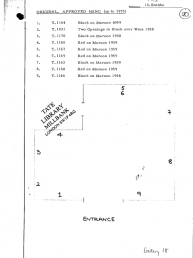

Rothko’s Instructions for Hanging the Murals

When Rothko’s murals arrived at the Tate Gallery in London on 25 February 1970, the Tate had clear instructions as to how they should be hung, what wall colour should be used and what lighting was necessary. These instructions came in the shape of Rothko’s personal suggestions to the Whitechapel Gallery, which had hosted a Rothko exhibition in 1961, containing eight of the Seagram Murals. The Tate still honours Rothko’s suggestions for the installation of his paintings up to this day:

“Wall Color: Walls should be made considerably off-white with umber and warmed by a little red. If the walls are too white, they are always fighting against the pictures which turn greenish because of the predominance of red in the pictures.

Lighting: The light, whether natural or artificial, should not be too strong: the pictures have their own inner light and if there is too much light, the color in the picture is washed out and a distortion of their look occurs. The ideal situation would be to hang them in a normally lit room – that is the way they were painted. They should not be over-lit or romanticized by spots; this results in a distortion of their meaning. They should either be lighted from a great distance or indirectly by casting lights at the ceiling or the floor. Above all, the entire picture should be evenly lighted and not strongly.

Hanging height from the floor: The larger pictures should all be hung as close to the floor as possible, ideally not more than six inches above it. In the case of the small pictures, they should be somewhat raised but not “skied” (never hung towards the ceiling). Again this is the way the pictures were painted. If this is not observed, the proportions of the rectangles become distorted and the picture changes.

The exceptions to this are the pictures which are enumerated below which were painted as murals actually to be hung at a greater height. These are:

1 Sketch for Mural, No 1, 1958

2 Mural Sections 2, 3, 4, 5, and 7, 1958-9

3 White and Black on Wine, 1958

The murals were painted at a height of 4′ 6″ above the floor. If it is not possible to raise them to that extent, any raising above three feet would contribute to their advantage and original effect.”

(Letter from Mark Rothko to the Whitechapel Gallery, 1961, Whitechapel Art Gallery Archive, London)

Rothko’s Place

In the Rothko Room at the Tate Modern, the Seagram Murals have found that place that Rothko so desired for them. Here, visitors are able to feel the full force of being fully surrounded by his mural works. The room in the middle of the museum becomes like a chapel for contemplation and deep personal experiences. To close with the words of author John Banville:

“The room is one of the strangest, most compelling and entirely alarming experiences to be had in any gallery anywhere. What strikes one on first entering is the nature of the silence, suspended in this shadowed vault like the silence of death itself – not a death after illness or old age, but at the end of some terrible act of sacrifice and atonement.”