The Drive to Classify Art Movements

A Different Form of Creation

By Peter Letzelter-Smith

The urge to create art is as deeply embedded in human history as the drive to make tools or migrate over the horizon. It is one of the primal acts that make Homo sapiens human.

To quote the influential art critic John Berger about the cave paintings of the earliest humans:

“What distinguished man from animals was the human capacity for symbolic thought, the capacity which was inseparable from the development of language in which words were not mere signals, but signifies of something other than themselves.”

As humans slowly coalesced their cultures into civilizations, the categorization of art took hold. Springing from another source of human creation — the drive to catalog and sort experience into orderly form — art history and criticism developed. Like the scientific method, it is an attempt to bring order to the chaos of creation.

Not surprisingly, the classification of art in the West began with the ancient Greeks and flowed forward to the Romans (though similar treatises about art were being produced in China at approximately the same time). From both the style and the study of Greek and Roman art came modern Classicism, the foundational style of art in Western civilization. Central to art and architecture well into the 19th century, Classicism is marked by its underlying requirement for symmetry and reference to the foundational myths of ancient Greece and Rome.

Prior to the modern era — basically from the fall of the Roman Empire to the 19th century — Western art was less diverse than the phalanx of styles now encompassed under the contemporary rubric of modern and postmodern art. That is not to say less powerful, only that medieval European society was more linear, with power and wealth — and thus the patronage necessary for the creation of formal art (as opposed to the rich traditions of folk art) — flowing down from the nobility and the Catholic Church, with little opportunity for the vast majority of people to push art “upwards” into their culture.

The Romanesque, Gothic, Renaissance, and Baroque styles all obviously produced powerful works of art — some of the most potent creations of human civilization. But these styles dominated the formal arts during their reigns and reflected a society more controlled than the sprawling, global culture that was unleashed by the Industrial Revolution.

Styles of art began to spring up during the 19th century. They were reactions to both the massive cultural upheavals that were occurring and the spread of wealth that provided new funding opportunities to artists. Scholars differ on the definitive moment when art became “modern.”

Some argue for Romanticism, a late 17th-century movement that emphasized the experience of the individual and embraced the “natural” world — especially the work of Francisco Goya, most notably his candidly political paintings in response to the Napoleonic invasion of Spain in 1808. Though his work was still stylistically rooted in both Classicism and the Renaissance, Goya’s individual struggle to process the political upheavals of his day — as opposed to simply continuing as a court painter as he was earlier in his career — is strikingly contemporary.

Other artists and styles developed during the mid-19th century. Clearly, by the time Impressionism exploded on the Parisian art scene in the 1870s the transition to modern art was complete. The coalescing of artistic technique in opposition to the dictates of Classicism — an emphasis on the play of light over form and unusual angles of perception — and the development of alternative ways for artists to market themselves in a more consumer-orientated economy are the foundation of today’s art scene.

The end of the 19th century and first quarter of the 20th century brought huge shifts in political and intellectual understanding — from the nonsensical horror of World War I to Einstein’s theory of relativity to the development of psychology — that pushed artists to create diverse works that attempted to process all this change. Also, the colonial powers pilfering art from other cultures spanning the globe — which were brought back to Europe for public exhibition — also profoundly impacted many artists, serving as an introduction to radically different forms of artistic creation.

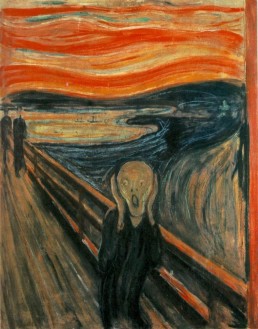

During this era, Art Nouveau, Cubism, Expressionism, Dadaism, Futurism, Post-Impressionism, Surrealism, and a host of other art styles and art movements sprang up as the Western world changed radically. This was a period that saw the introduction of the airplane, automobile, radio, and telephone into daily life. It was a time of monumental change in human history and artists struggled in diverse and startling ways to come to terms with it.

Clearly, these forces continued to play out for the rest of the 20th and 21st centuries. As human culture continued to diversify and “globalize,” movements such as Abstract Expressionism, Conceptual Art, Installation Art, Land Art/Earth Art, Minimalism, Performance Art, and Pop Art developed. All these styles encompass works that attempt to capture the vitality and fears of the modern world. The proliferation of formal styles is an attempt to quantify the vast array of modern artistic expression.

Get your free copy of Artland Magazine

More than 60 pages interviews with insightful collectors.