Articles and Features

The Other Salvador Dalí: How the King of Surrealism Made his Mark on Cinema

By Shira Wolfe

“Give me two hours a day of activity, and I’ll take the other twenty-two in dreams.”

Salvador Dalí

In this article series, we explore the lesser-known artistic output of artists who became known for another medium or genre of art. Often, great artists wear many different hats, but break through and achieve acclaim because of their work in one specific medium. We aim to highlight the multifaceted nature of their talent by shining a light not on what they are best known for, but on the lesser-known side of their artistic production. This week, we explore the various cinema projects of the great Surrealist master Salvador Dalí who, despite being famous for his painting, also made his indelible mark on cinema.

Un Chien Andalou (1929)

In 1929 in Paris, Luis Buñuel told Salvador Dalí about a dream he had had, in which a razor blade sliced open an eyeball. Dalí then shared his dream with Buñuel, about a hand crawling with ants. Inspired by these powerful images, Dalí convinced Buñuel to make a film together: the movie would be based solely on their dreams and focused on the emotions they felt, abandoning the traditional notion of a linear plot, and logic. At the time, Buñuel was already working as an assistant director in the French film industry, but this movie would be the beginning of something completely new for him.

Buñuel and Dalí agreed that the movie should be filled with irrationality and images without explanation. The script was completed in 6 days.

Un Chien Andalou begins with that very image from Buñuel’s dream: a man slicing open a woman’s eyeball with a razor blade, immediately followed by a cloud passing over the moon, as though it is slicing it open. Other surreal scenes include the hand crawling with ants, a man dragging two pianos containing the corpses of two donkeys across a room, and a man’s mouth disappearing suddenly from his face. Buñuel and Dalí had expected a riot to break out, but the film was met with a positive reception and many famous Parisian artists like Picasso, Jean Cocteau, and André Breton, attended the movie’s premiere. While Buñuel was relieved, the flamboyant Dalí, who loved a bit of drama, was quite disappointed. Un Chien Andalou led to an invitation to both Dalí and Buñuel to join the Surrealist movement. Instead of the hoped-for turmoil, the artists ironically received 1 million Francs from wealthy French patrons to make a sequel to Un Chien Andalou. However, they could not seem to come to an agreement on how to approach the film, and their relationship eventually came to an end. Dalí left the project, and Buñuel continued on his own and turned the project into his hour-long movie L’Âge d’Or (1930). Dalí criticised the film as he claimed it was an aggression against Catholicism, and the film was in fact banned at the time due to its blasphemous nature.

Spellbound (1945)

During World War II, Dalí and his wife Gala fled to the United States. Americans loved Dalí and his art, and he loved them and their large amounts of money, right back. In 1945, Dalí was approached by Alfred Hitchcock to design the dream sequence for his new movie Spellbound, starring Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck. In an interview, Hitchcock elaborates on his choice of Dalí for this scene:

“I requested Dalí. Selznick, the producer, had the impression that I wanted Dalí for the publicity value. That wasn’t it at all. What I was after was again the thing we talked about earlier. The vividness of dreams. As you know, all Dalí’s work is very solid and very sharp, with very long perspectives and black shadows. Actually I wanted the dream sequences to be shot on the back lot, not in the studio at all. I wanted them to be shot in the bright sunshine so the camera man would be forced to, what we call, stop down, and get a very hard image. This was, again, the avoidance of the cliché. All dreams in movies are blurred. It isn’t true. Dalí was the best man for me to do the dreams because that’s what dreams should be.”

Dalí envisioned the dream sequence to last 20 minutes, but in the end, it was cut short to roughly three minutes. Some ideas were also discarded from the start, as they would be too complicated to film, such as a ballroom scene with 15 grand pianos suspended from the ceiling. Other scenes were cut after Dalí and Hitchcock had left the set. These decisions mostly came from the film’s producer, David O. Selznick, who became increasingly concerned about the scene, and wrote: “The more I look at the dream sequence for Spellbound, the worse I feel it to be… It’s not Dalí’s fault, for his work is much finer and much better for the purpose than I ever thought it would be. It is the photography, set-ups, lighting, et cetera.”

Spellbound went on to receive rave reviews and was nominated for six Academy Awards, winning the Best Original Score for its soundtrack. However, Dalí believed the best parts of the film had been cut and did not ever speak much about his involvement in the movie afterwards, likely being disappointed by how many of his ideas were cut. Still, Dalí’s dream sequence remains a beautiful example of how his vision translated from visual art to cinema.

“There is only one difference between a madman and me. The madman thinks he is sane. I know I am mad.”

Salvador Dalí

Salvador Dalí (1966)

In 1966, Dalí starred in two of Andy Warhol’s famous screen tests. Warhol filmed nearly 500 of these screen tests in the mid-60s, and many of his subjects were celebrities. Warhol first met Dalí at the St. Regis Hotel in New York, and was overwhelmed by the experience of meeting the Surrealist legend. When Dalí sat for the screen tests, he challenged many of Warhol’s general rules and the strict set-up that he had stuck to previously: in one of the screen tests, Dalí is filmed upside down, and in the other, he vanishes from the screen midway through the test. Warhol continued to be fascinated by Dalí and went on to film Salvador Dalí in 1966, a 35-minute film starring Dalí visiting the Factory and meeting the band members of The Velvet Underground.

Impressions de la Haute Mongolie (1975)

The last movie Dalí worked on in his lifetime was Impressions de la Haute Mongolie in 1975. He wanted to create an homage to the French writer Raymond Roussel (1877-1933), a forerunner of the Surrealists whom he admired greatly. According to Dalí, Roussel was a precursor of his paranoiac-critical method. In order to express his admiration for the writer, Dalí conceived this experimental film as a fantastic journey through Upper Mongolia, loosely inspired by Roussel’s self-published 1910 novel Impressions of Africa, in which he describes his impressions of Africa, which he never actually visited.

Dalí asked the director José Montes-Bacquer to work on the film with him, and together they developed this 50-minute adventure, in which Dalí himself stars as well. The story revolves around a Mongol princess who feeds her subjects magic mushrooms which produce hallucinations and stimulate them to paint. The film shows a scientific expedition, sent to Upper Mongolia to find the hallucinogenic mushroom. The movie is filled with Surrealist imagery, bizarre occurrences, and Dalí’s highly entertaining dramatic overacting.

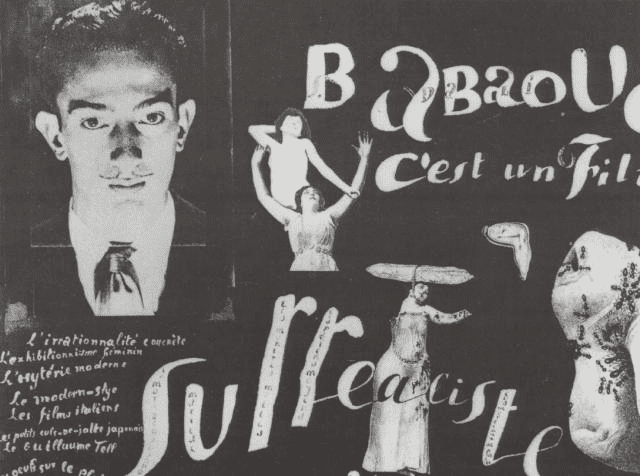

Babaouo (1997)

In 1997, eight years after Dalí’s death, the director Manuel Cussó-Ferrer made Babaouo, a film based on an original screenplay of the same name written by Dalí in 1932. At the time of its conception, Dalí intended for Babaouo to become a Surrealist film, something along the lines of Un Chien Andalou. The story was filled with Dalí’s Surrealist images such as melting watches and burning giraffes. However, nothing besides the screenplay, some designs, and the poster was completed, and Dalí abandoned the project.

As per Dalí’s original intentions, the film takes place in 1934 in a European country during the civil war. The movie follows Babaouo, who is on a quest to find his love Matilde. She has sent him a letter from a castle in Portugal asking for his help. After all kinds of encounters and strange situations during his journey, Babaouo finds Matilde and they escape. However, their car crashes, Matilde dies, and Babaouo is blinded. When he regains his sight, he decides to become an artist.

Destino (2003)

In America, besides his work on Spellbound in 1945, Dalí had also tried to collaborate with the Marx Brothers and Walt Disney on movie projects. However, to his great disappointment, both projects fell through. Dalí’s 1937 screenplay Giraffes on Horseback Salad, which he had written for the Marx Brothers, turned out to be just a bit too surreal for the studio which declined the projects. Dalí had envisioned scenes of giraffes in gas masks set on fire, and Harpo Marx catching dwarves with a butterfly net.

Between 1945 and 1946, Dalí and Disney studio artist John Hench worked on the storyboard for Destino (Spanish for “Destiny”). But this project was stopped early on as well. Walt Disney Studios were struggling with financial problems due to World War II, and the production was ultimately considered financially unviable and put on hold indefinitely. In 1999, Walt Disney’s nephew Roy E. Disney decided to bring the project back to life. He brought Walt Disney Studios Paris on board to complete the project. The short movie, which is only 7 minutes long, was directed by French animator Dominique Monféry. Approximately 25 animators worked together to decipher Dalí and Hench’s original storyboards. Gala Dalí and Hench, who were both still alive at the time, helped them to understand the cryptic storyboards as well, and Dalí’s journals offered some clues too. The result is mostly traditional animation including Hench’s original footage, with some computer animation here and there.

The story of Destino shows the ill-fated love of Chronos for a mortal woman named Dahlia. We see Dahlia dancing through surreal scenery inspired by Dalí’s paintings. 17 seconds of original footage is included in the film: the segment with two tortoises.

Dalí’s visionary art and eccentric mind were clearly very well suited to the medium of film, and his iconic Surrealist images live on through these versatile movie projects.

Relevant sources to learn more

Salvador Dalí Museum

Salvador Dalí Foundation

MoMA

BBC documentary about Dalí