Articles and Features

The Visual Poetry of Suh Se Ok: Between Tradition and Modernism

“You cannot forget that ink painting is a living thing”.

Suh Se Ok

When considering major artistic revolutions, one immediately thinks of breakthrough technologies, grand gestures, and charismatic personalities.

In postcolonial Korea, however, a dramatic change took place by means of notably simpler ingredients: a brush, a sheet of rice and mulberry paper, and a pale Indian ink bottle.

Equipped with such outwardly simple tools, Korean artist Suh Se Ok questioned the preordained systems of art, ultimately guiding the path of Korean contemporary art.

Modernism pioneer, he merged traditional techniques with the modern spirit, figuration with abstraction, painting with poetry, revealing the power of simplicity to the world.

“I did not want to exhibit only one line of thinking, I think of my works as a flight towards every possibility”.

Suh Se Ok

Early Life

Born in 1929 in Daegu, Korea, Suh Se-ok grew up in tumultuous times in Korean history, witnessing both the Japanese colonial occupation (1910-45) – his father was a Korean independence activist during the Japanese colonial rule – and the brutal war and turmoil that followed.

In 1949, soon after the establishment of the Government of Republic of Korea, Suh Se Ok made his debut in the art scene under the nom de plume of Sanjeong by winning the first edition of the National Art Exhibition, and in Korea’s pursuit of an authentic artistic identity, deliberately freed from the techniques and materials imposed by the imperial Japanese state, he forged his own path, developing an idiosyncratic visual language, as innovative, as it was rooted in ancient traditions.

In 1950, he graduated with a painting degree from the prestigious Seoul National University, where he would teach from 1955, mentoring younger generations of artists for four decades.

Mungnimhoe: the Ink Forest Society

With the aim of purging from Korean art the Japanese influence, but also breaking away from the then dominating representational art style associated with the National Art exhibition system, many Korean artists began to regard what was happening in Europe and the United States, finding particular inspiration in the dramatic gestures and thick textures of Art Informel.

However, a small yet ambitious group of ink painters, concerned with how quickly “Korean Informel” seemed to monopolise the artistic scene, championed an entirely different approach and an artistic research focused on experimental forms of ink paintings.

It was Suh Se Ok who brought these artists together and formed, in 1959, the Mungnimhoe, the Ink Forest Society, a radical group devoted to modernising Korean art while remaining committed to the traditional medium. In a 1966 panel discussion, he stated: “If the Korean avant-garde continued to appropriate from Western avant-garde, it would soon lose its understanding of art altogether”.

Approaching the medium with awareness and sensitivity, the Ink Forest Society members went back to the origin of the ink painting technique, highlighting its delicate nature and essential elements: ink, water, and paper; ultimately finding in the bare simplicity of brushstrokes tracing dots and lines a powerful means of expression.

Despite stemming from local traditions, the Mungnimhoe group valued internationalism and participated – until its dissolution in 1964 – to major art biennales and triennials across the globe, including the 1963 San Paulo Biennale.

Suh Se Ok: Style and Influences

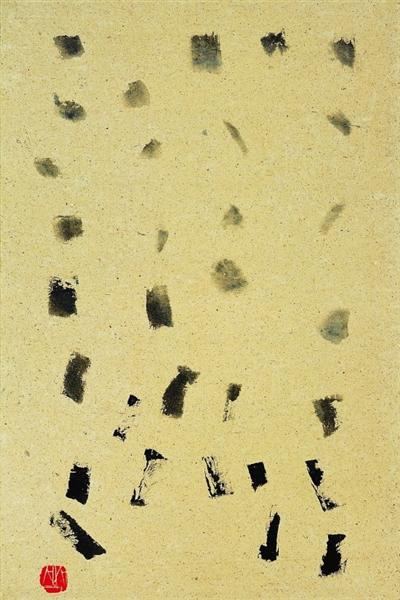

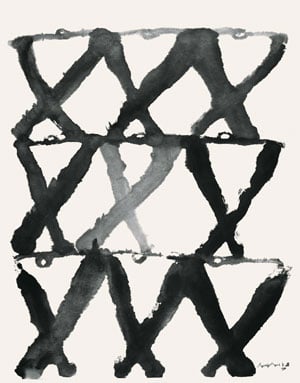

Suh worked with colour as well as with monochrome ink to produce poetic compositions: vibrant lines, dashes and dots that vary in scale, thickness, and tone – webs of ink in the intersection between abstraction and stylised figuration.

The artist’s main source of inspiration was Muninhwa or ‘literati painting’, a genre which originated in China in the eleventh and twelfth centuries and became popular in Korea during the Joseon dynasty (1392–1897).

This art form, traditionally practised by noble scholars, fused painting, poetry, and calligraphy as “three forms of one body”, and valued spontaneity and self-expression above all.

Suh was able to push the genre to its limits, adapting its elements to his generation’s expressive needs and the political context of his country.

In his most famous People series, in fact, one can easily recognise abstracted sketches of human society. “I depict many sides of human figures. I express numerous people’s joy, anger, sadness and pleasure”, he once stated.

Executed in a single substantial stroke, a rhythmic sequence of marks plays with the pictogram that means ‘person’ (人) and symbolises interconnected human figures almost moving hand-in-hand.

In the mid-seventies, he directed his attentions toward the tension between positive and negative space, addressing the theme of the void: “I paint the forms that I find in the infinite space beyond objects”, he said. “What is there and what is not there are in a constant cycle”.

Suh lived and worked in Seoul for most of his life but exhibited his work worldwide, proving the universal quality of his creative language.

His recent solo exhibitions include the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul and Gwacheon, Korea (2015, 2005); Museum of Fine Arts Houston, TX (2008); and Maison Hermes, Tokyo, Japan (2007). The latter saw the collaboration with his son – and fellow artist – Do Ho to present an installation work made with his painting on a large-scale translucent fabric.

Suh Seh Ok died in 2020 at the age of 91, leaving an important statement on art as his legacy. With striking simplicity and a bare minimum of materials, he developed a timeless body of work and made of spontaneity and incompletion his signature style.

In conversation with Kim Byung Jong, professor of Oriental Painting at Seoul National University, Suh declared: “There is no such thing as great completion. Always a continuation of uncertainty and incompletion. There exists possibly no perfect life or perfect art. If there is such a thing, then I will have to put my brush down. And that will terminate our life, too. But no, that is not the case. We go on in the state of incompletion”.

Relevant sources to learn more

Suh Se Ok, Special Exhibition of Donated Works – National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art

Read about Dansaekhwa: The Meditative Korean Art of Monochrome Painting