Articles and Features

Exploring Dansaekhwa: The Meditative Korean Art of Monochrome Painting

By Adam Hencz

“While Western monochrome painting focuses on the visual, Dansaekhwa is of a tactile quality and expresses the Korean philosophy of assimilation with nature. It is created from an ecological, cosmological, and earthly viewpoint, in contrast to the formalistic perspective of the West.“

Noh Sang-Kyoon

The South Korean art auction market is experiencing its biggest boom in decades, attracting buyers from wealthy investors to audiences not particularly interested in contemporary Korean art, but fascinated by abstract art in general. Since then, especially after 2013, Dansaekhwa has become the international face of contemporary Korean art, capturing the art world’s attention. Everything started in 2006 when Lee Ufan, the iconic pioneer of the movement, left Korea for Tokyo and his work started being exhibited at Pace Gallery in New York and Lisson Gallery in London. The fame of the now 85-year-old artist resulted in the rise of other artists associated with the Dansaekhwa movement, and who were subsequently catapulted to international fame. Also dubbed as the ‘Korean monochrome painting movement’ or simply ‘Korean Abstraction’, Dansaekhwa shares many traits with modernism – with American Minimalism in particular – combined with meditative calligraphy and Taoist and Buddhist philosophy. Many artists associated with Dansaekhwa developed their distinctive signature style, but their work is united by a timeless visual language and a strong emphasis on materiality and production techniques.

What is Dansaekhwa?

Never formally conceived as an art movement, Dansaekhwa refers to a loosely connected group of abstract painters that originated in South Korea who primarily worked in the 1970s. After a turbulent period of social and economic crises, artists of post-war Korea embraced Taoist and Buddhist ideas to find peace of mind. The meticulous practice of producing works, the painting process, and the creative act itself served as a self-healing journey for a generation of Korean artists that grew up in the midst of the chaos of the Korean war. They wished for a break with traditional Korean art and embraced experimental methods like tearing drawing paper, dragging the pencil, or soaking the canvas to create works and to manipulate them in unconventional ways. Creating patterns with the act of repetition is central to the practice of these artists. This process-driven approach and philosophical charge played an important role in the sustained interest in both contemporary Asian art history and Korean abstract art.

Dansaekhwa & Minimalism

From the 1960s onwards, Western influence in Korean art slowly became apparent, although artists deliberately transformed such influences into techniques, processes, and styles that are explicitly their own. At that time, more attention was paid to works that used modern art as a tool to preserve the traditions of the time. On the other hand, the Korean monochrome art movement of the 1970s was rather a conscious development of traditional aesthetics that borrowed elements from Minimalism, a modern art trend from America that had its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s. A common feature of Dansaekhwa and Minimalism is that many artists working during that period tried to create their works with as little use of tools and materials as possible. Even though Dansaekhwa and Minimalism share similarities and are visually resembling, Korean abstract art is conceptually unique and is profoundly rooted in tradition.

Famous Dansaekhwa artists

Kim Tschang-Yeul

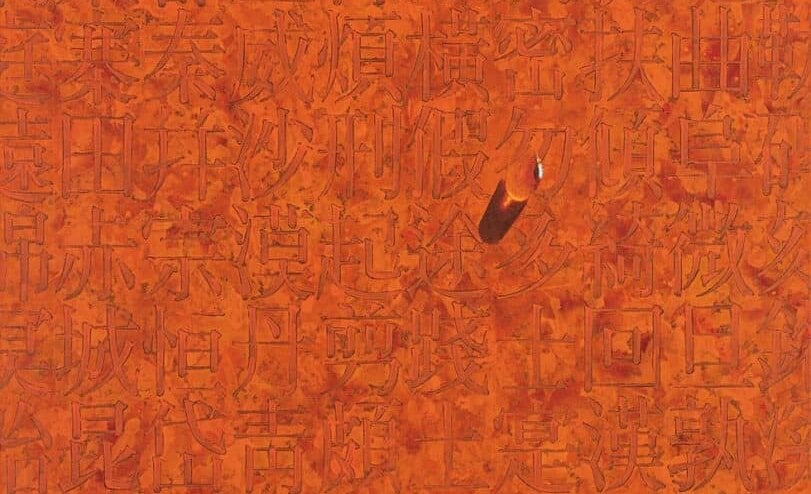

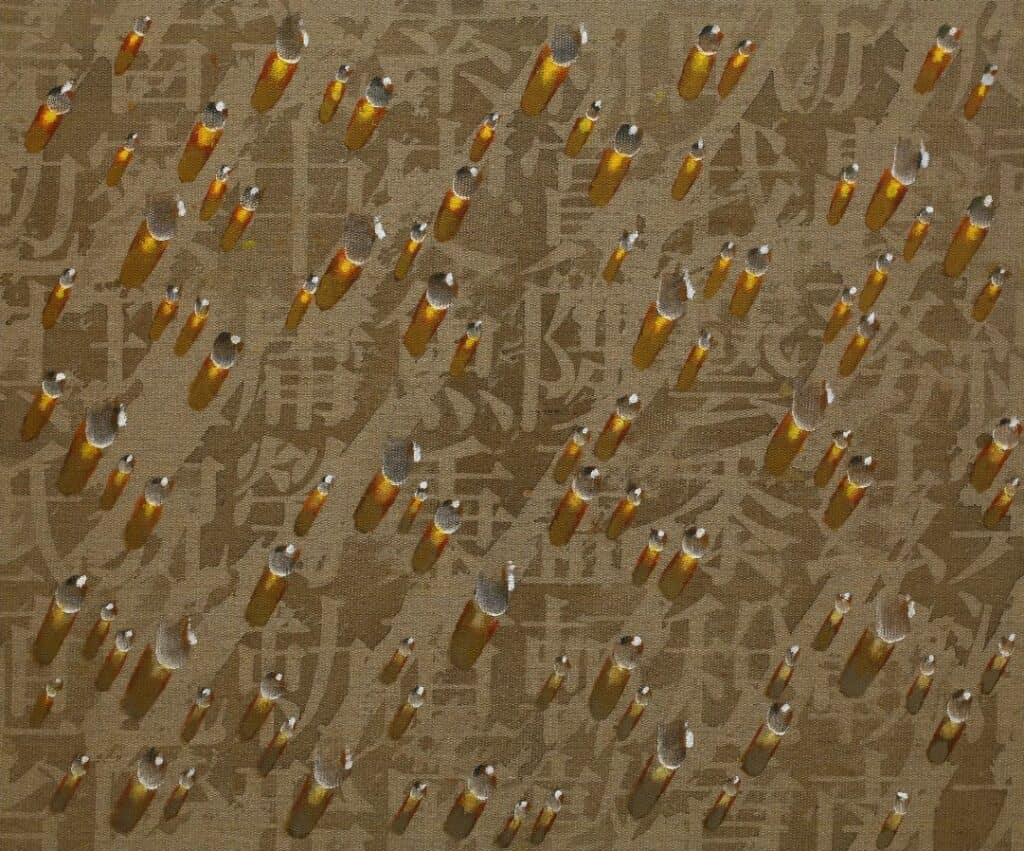

Water drops are synonymous with the name of the vanguard of the Dansaekhwa movement, Kim Tschang-Yeul. Kim Tschang-Yeul joined the Korean Informel movement in the 1950s and led contemporary Korean art to the international scene until his recent passing in 2021. In the 1960s, Kim settled in Paris and started to experiment with natural motifs, and expressed his sensitivity to the poetics of water, a subject that he would continue to pursue for more than fifty years. Water drops are the symbol of his Taoist wisdom as well as the tragedies experienced during the Korean war. The recurrent theme of water drops was often paired with Korean calligraphy in his oeuvre after the 1980s. His late works combine the water drop motif with traditional calligraphy practice, blurring the lines of image and text and bridging the abstract and the figurative, the East and the West.

Suh Se-Ok

Along with Kim Tschang-Yeul, Suh Se-Ok was among the founders of the Art Informel movement in the mid-1950s and early 1960s. Suh Se-Ok was a leading artist of abstract ink painting, who embraced abstraction and mixed modernism with traditional artistic practices such as East Asian calligraphy. He questioned the prevailing Western art trends and its obsession with decomposing elements into terms of horizontality and verticality. Suh Se-Ok passed away in 2020 and was an icon of Korean and contemporary art, one among the very few of his peers to receive global recognition.

Park Seo-Bo

In his early works, Park Seo-Bo used pencil engraved on a wet, monochromatic painted surface. His later works expanded that visual language by introducing hanji, a traditional Korean paper made from mulberry bark, which the artist gently adhered to the canvas. This development, along with the introduction of color to the traditional surface, allowed for an extensive transformation of his practice while continuing to search for the depiction of space and emptiness through reduction. Due to this distinctive process used to create his works, Park Seo-Bo began to open new doors for contemporary Korean art and created a synthesis between the traditional Korean spirit and Western abstraction.

Hyun Ae Kang

Belonging to the second generation of Korean Dansaekhwa, Hyun Ae Kang is a South Korean artist based in the United States. Working in a variety of media and materials – from metal and wood to stone, ceramics, and paint, she investigates her own relationship with the divine through the exploration of highly detailed textures, and color combinations, blurring the line between creative practice, meditation, and spirituality. She stated:

“All the touches and strokes I use are inscriptions of the dialogues with the sacred. These inscriptions are based on Korean alphabet characters and glyphs. When I create my reliefs onto the canvases, I think of myself as a scribe that is carving messages from the heavenly force into the worldly materials of stones and pumice. And with these inscriptions, I hope viewers will be able to reflect upon them and gain insights they could have not achieved beforehand.”

Hyun Ae Kang’s work is part of public institutions and private collections alike, and her work has been featured in solo and group exhibitions throughout the United States, Europe, and Asia. In 2020, BOCCARA ART Galleries presented a solo show of the artist at ‘Museo dei Bozzetti’ in Pietrasanta, Italy, which can be visited on Artland.

Wondering where to start?