Articles and Features

Top American Photographers of the American experience

On the road and of the streets

Road trips and the streets have been essential subjects for American photographers and key components of the ways they have visually recorded and communicated the social and cultural signifiers of the American experience in the Twentieth Century. As a homage to the legendary Robert Frank, who died this week and whose work The Americans is perhaps more emblematic of this attitude than any other body of work, we take a look at the American photographers who shaped the aesthetic of a nation, its sense of self and the perception of it around the world.

1. Alfred Stieglitz

“In photography there is a reality so subtle that it becomes more real than reality”

Alfred Stieglitz was an American photographer and early proponent of the medium as an art form. He worked as both a leading fine art photographer, and also as a promoter and dealer of modern art and photography. His galleries in downtown NYC in the early part of the twentieth century were legendary for their salons, and for the introduction of leading members of the European avant-garde to the United States. As early as the 1890s he considered himself a fine artist working in the medium of photography, and became an influential authority on this emerging medium. Through his editorship of The American Amateur Photographer, his publication of Camera Work, his curatorial work including Photo-Secession, and ultimately his stewardship of the 291 gallery, and latterly An American Place, his manifold activities made him one of the most influential shapers of artistic taste in the twentieth century. Known for his perfectionism and fastidious standards both artistically and technically he became the archetypal artist documenter of modern American life at the beginning of the twentieth century. In his later life he began a deep and abiding relationship with Georgia O’Keefe, who became both the muse and kindred spirit he had always craved.

2. Walker Evans

“I used to try to figure out precisely what I was seeing all the time, until I discovered I didn’t need to. If the thing is there, why, there it is.”

Walker Evans was an American photographer and photojournalist whose renown and reputation was formed during the period of The Great Depression. He travelled extensively on commission for the Farm Security Administration documenting the effects of the economic hardship on swathes of the rural population. His stated goal was to make photographs that were “literate, authoritative, transcendent”, and was particularly interested in exploring small towns and their idiosyncrasies in pursuit of it. Impressed by August Sander and Eugene Atget, two great European modernists, Walker absorbed their influence and began making photographs in the late 1920s. Evans, like such other photographers as Henri Cartier-Bresson, rarely spent time in the darkroom making prints from his own negatives. Known for his work with a large format camera, he was less fastidious about printing and only very loosely supervised the making of prints of most of his photographs, occasionally only attaching handwritten notes to negatives with instructions on some aspect of the printing procedure. In 1938 his work was shown in an exhibition at MoMA—entitled Walker Evans: American Photographs—the first time the fabled museum had devoted an exhibition to the work of a single photographer. The book that arose gave birth to the idea that a travelling photographer could shoot and sequence a body of photographs to communicate a summation of a nation.

3. Robert Frank

“When people look at my pictures I want them to feel the way they do when they want to read a line of a poem twice.”

Robert Frank was a Swiss photographer who immigrated to the United States in 1947 and adopted dual nationality. Born in Zurich he lived intermittently between Europe, the USA and travelled extensively until later in the 1950s. In 1951 he was included in the seminal exhibition 51 American Photographers by Edward Steichen. Though he was initially enthralled by American life and optimistic about the society and culture there, Frank’s perspective began to change as he was confronted by the fast pace of American life and what he saw as an overemphasis on capitalism and financial ambition. He came to see America as a bleak and lonely place, a perspective that became evident in his later photography. Associating with other contemporary photographers such as Saul Leiter and Diane Arbus, he helped form what came to be termed The New York School of photographers during the 1940s and 1950s. In 1955, seven of Frank’s photographs (many more than most other contributors) were included in the world-touring Museum of Modern Art exhibition The Family of Man that was to be seen by 9 million visitors and with a popular catalogue that is still in print. The achievement for which he is best known, and what is today regarded as the most important body of work to set the tone of American road photography is The Americans, commenced in 1955. Undertaking to travel across the United States and photograph all strata of its society in many different cities, Frank’s own view of his role and that of the work is clear—he values honesty and candour above all else. Frank’s project was an immense one: in this period he shot over 27,000 images, which he later condensed to a mere 83, each image as powerful as the ones preceding or following them. They speak of the diverse, varied peoples and landscapes of the USA, and the burden of the American dream (and desire to escape it) innate to its people. Introduced by Jack Kerouac, The Americans is both a celebration and critique of Frank’s contemporary society, which was met bitterly by the critics of his day, but is now remembered as a masterpiece.

4. Helen Levitt

“All I can say about the work I try to do, is that the aesthetic is in reality itself.”

Helen Levitt was an American photographer particularly noted for street photography around New York City, a habit she practised for almost 70 years. She has been called “the most celebrated and least known photographer of her time.” She dropped out of high school before graduating and in 1931 she learned the processes for developing photos in the darkroom whilst working for a commercial portrait photographer in the Bronx. Her fascination grew with the medium and she used to visit Manhattan to see the work of master photographers in the city’s galleries. She saw the work of Henri Cartier-Bresson, a large influence on her career, at the Julien Levy Gallery and came to view photography as the most important modern art form. She developed her skills by practicing photographing her mother’s friends, whilst venturing into street photography mainly in East Harlem but also in the Garment District and on the Lower East Side, all in Manhattan. During the 1930s to 1940s, the lack of air conditioning meant people were outside more, which enabled her to work almost solely on the street photography idiom. Her work was first published in Fortune magazine’s July 1939 issue. Her interest in Cartier Bresson came full circle when she accompanied him on a day of shooting in New York City, and she was also mentored by Walker Evans, who felt her work was among the most interesting of all contemporary photographers. Levitt received her first grant in 1946 from the Museum of Modern Art. In 1959 and 1960, she received two grants from Guggenheim Foundation for her pioneering work in colour photography. In 1965 she published her first major collection, A Way of Seeing.

5. Garry Winogrand

“Sometimes I feel like . . . the world is a place I bought a ticket to. It’s a big show for me, as if it wouldn’t happen if I wasn’t there with a camera.”

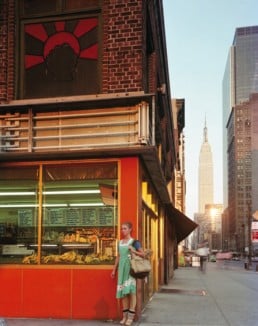

Garry Winogrand was born in New York, where he lived and worked during much of his life. Winogrand photographed the visual energy of city streets, people, rodeos, airports and animals in zoos, and whilst he did so across the United States, it is for his work in New York City that he is most remembered. Winogrand was the recipient of numerous grants, including an unprecedented three Guggenheim Fellowships and a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship. He was highly regarded and influential for his street photographs documenting the social issues and cultural landscape of mid-century metropolitan United States. Shot almost exclusively in black and white, Winogrand’s images provide a rich slice of 20th-century American culture, bristling with the eccentric vibrancy of the nightlife, excitement, heartbreak, trauma, and banality that constitutes the city life he captured. “Photography is not about the thing photographed,” he famously said. “It is about how that thing looks photographed.” Born on January 14, 1928 in the Bronx, NY, he studied painting and photography at City College and Columbia University and graduated in 1948. He participated in the groundbreaking 1955 exhibition The Family of Man at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, an exhibition which subsequently toured worldwide to an audience of nine million people. Winogrand’s later life and work was marked with landmark acclaim and success, with a plethora of exhibitions including a major retrospective at The Museum of Modern Art in 1988. At the time of his death his late work remained largely unprocessed, with about 2,500 rolls of undeveloped film, 6,500 rolls of developed but not proofed exposures, and about 3,000 rolls realized only as contact sheets. In total he left nearly 300,000 unedited images to accompany his reputation as the seminal photographer of the mid century period. Winogrand may not have invented street photography, but he transformed it from an art of observation to an art of participation.

6. Lee Friedlander

“You don’t have to go looking for pictures. The material is generous. You go out and the pictures are staring at you.”

Lee Friedlander was a highly influential photographer of the 1960s and 70s, who evolved an innovative and often imitated visual language of street photography, developing a type of urban “social landscape,”. He instigated a new kind of compositional style with many of his photographs including fragments of store-front reflections, structures framed by fences, posters and street signs—using elements of the composition to further highlight a part of that image within the frame. The ability to organise vast amounts of visual information, coupled with the deliberate fragmentation and ambiguity of compositions became Friedlander’s trademark. Born in the Pacific North West in Washington, Friedlander moved to New York City in 1956, where he gained work photographing jazz musicians for record covers. His early work was influenced by Eugène Atget, Robert Frank, and Walker Evans. In 1960 Friedlander was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship to focus on his art, and was awarded subsequent grants in 1962 and 1977. Along with his NY colleagues Garry Winogrand and Diane Arbus, he was a the vanguard of a generation of street photographers using a “snapshot aesthetic” to capture contemporary urban life with unflinching realism. In the tradition of his predecessors Robert Frank and Walker Evans, Friedlander took frequent road trips throughout the United States, and the people and places he saw on those trips became his primary source material. In 1962–63 he photographed small televisions left on in empty rooms, a ubiquitous symbol of modern life in houses and motels throughout the country. The photographs are named by the city in which they were taken and include no people. In 1963 Harper’s Bazaar published the series alongside an essay by Evans, in which he praised Friedlander’s work. That same year Friedlander had his first solo exhibition at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York.

7. William Eggleston

“I only ever take one picture of one thing. Literally. Never two. So then that picture is taken and then the next one is waiting somewhere else”

William Eggleston is one of the most influential photographers of the latter half of the 20th century. His portraits and landscapes of America, and especially the South, have reframed the potentials of the medium and the previously understood applications of it. Eggleston’s initial style was influenced by Henri Cartier-Bresson, Robert Frank, and Walker Evans. He attended Vanderbilt University, Delta State College, and the University of Mississippi, but never graduated. The artist’s experiments with color film during the early 1960s challenged the conventions of photography, since at the time, colour photography was considered beneath the dignity of serious photographers, relegated to commercial prints and tourist snapshots. Color transparency film became his dominant medium in the later 1960s, but it was during the early 1970s teaching at Harvard that he discovered dye-transfer printing; he was examining the price list of a photographic lab in Chicago when he read about the process. As Eggleston later recalled: “It advertised ‘from the cheapest to the ultimate print.’ The ultimate print was a dye-transfer. I went straight up there to look and everything I saw was commercial work like pictures of cigarette packs or perfume bottles but the colour saturation and the quality of the ink was overwhelming. I couldn’t wait to see what a plain Eggleston picture would look like with the same process. Every photograph I subsequently printed with the process seemed fantastic and each one seemed better than the previous one.” The saturation and density of the color astounded him to the extent that he no longer printed in any other process. Eggleston’s works catalogue singular objects that somehow function as American tropes in both a poetic and regimented manner. Documenting everyday items, his works, along with those of his compatriot Stephen Shore, have created a visual encyclopaedia cataloguing and defining the vernacular of what we consider modern America.

8. Stephen Shore

“To see something spectacular and recognise it as a photographic possibility is not making a very big leap. But to see something ordinary, something you’d see every day, and recognize it as a photographic possibility – that is what I am interested in.”

Shore is an American photographer known for his images of banal scenes and, along with Eggleston, for his pioneering use of colour in art photography. His books include Uncommon Places, 1982 and American Surfaces, 1999; iconic collections of photographs taken on cross-country road trips in the 1970s. These books celebrate everyday life, focusing attention on things we routinely look at but never truly see. ‘I was interested more in the ordinary … I wanted to be visually aware as I went through the day. I started photographing everyone I met, every meal, every toilet, every bed I slept in, the streets I walked on, the towns I visited.’ The images in Uncommon Places indeed highlight Shore’s status as a traveller, and the books themselves have become symbols of the ultimate, and exhaustively observant, road trip. His introduction to photography came very early on — he received his first darkroom kit, a gift from his uncle, when he was just six years old. A prodigious talent, at the age of just 14, he sold three of his photographs to the photography department of the Museum of Modern Art, then under the ægis of Edward Steichen. In the 1960s he was in thrall to Andy Warhol and the culture of the Factory, becoming one of the habitués of this heady environment. In 1971 he was granted a solo exhibition at New York’s Metropolitan Museum, at the time the youngest ever recipient of such an honour. Progressively for a photographer of his generation and prestige, he has also embraced both digital photography and the venue of social media as a means of disseminating it.

9. Joel Meyerowitz

“Photography is a response that has to do with the momentary recognition of things. Suddenly you’re alive. A minute later there was nothing there. I just watched it evaporate. You look one moment and there’s everything, next moment it’s gone. Photography is very philosophical.”

Joel Meyerowitz is an American street, portrait and landscape photographer. He began photographing in color in 1962 and was an early proponent of the use of colour during a time when there was significant resistance to the idea of color photography in fine art circles. In the early 1970s he taught photography at the Cooper Union in New York City and his work can be found in the collections of the International Center of Photography, Museum of Modern Art, and New York Public Library, all in New York, and the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago. Inspired by street photographers such as Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Frank, a young Meyerowitz picked up a 35mm camera and began to document his own cultural landscape. Shifting between black-and-white and color film, Meyerowitz ultimately chose color as his primary medium, and moved from the handheld 35mm camera to a large-format view camera, greatly influencing his image-making technique by introducing a slower, meditative process, which in turn has enabled him to capture incredible effects of light in later bodies of work. Greatly influenced by Stephen Shore, Meyerowitz can also be described as an artist who has further elaborated the capturing of bizarre or stranger than fiction scenarios as a key element of his practice, often communicating extraordinary narrative content and showing the United States as a land of limitless possibility, incredible diversity and humorous eccentricity.

10. Alec Soth

“I fell in love with the process of taking pictures, with wandering around finding things. To me it feels like a kind of performance. The picture is a document of that performance.”

Alec Soth was born in Minnesota in 1969 and began to receive international acclaim when his photographs were featured in numerous solo and group exhibitions, including the 2004 Whitney and São Paulo Biennials. Soth’s photographic style has developed in series beginning with his iconic Sleeping by the Mississippi, and including NIAGARA, The Last Days of W and Broken Manual. Soth uses his large format camera to photograph the people and landscapes of suburban and rural communities, often during road trips throughout the Midwest and the South. His work is rooted in the distinctly American tradition of ‘on-the-road photography’ developed by American photographers Walker Evans, Robert Frank, and Stephen Shore. His work embodies an adventurous spirit that seeks out eccentricity in all its forms in oft-neglected corners of the United States. Sometimes imbued with the loneliness of the voyeur, Soth’s depictions of the strange corners of life are often filled with narrative pathos—mostly empathetic and profoundly poetic. New York Times art critic Hilarie M. Sheets wrote that he has made a “photographic career out of finding chemistry with strangers” and photographs “loners and dreamers”. In his work he seems to identify with a uniquely American desire to travel and chronicle the adventures that consequently ensue. He has received fellowships from the McKnight, Bush, and Jerome Foundations and was the recipient of the 2003 Santa Fe Prize for Photography. His photographs are represented in major public and private collections, including the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and the Walker Art Center. His work has been widely featured internationally in galleries and museums, including a career survey at the Jeu de Paume in 2008.