Articles & Features

Unfinished Art: The Enduring Fascination Of Incompleteness

“There is a great difference between a work that is ‘complete’ and a work that is ‘finished’; that in general what is ‘completed’ is not ‘finished’, and that a thing that is highly ‘finished’ does not need to be ‘complete’ at all“.

Charles Baudelaire

“She held out her trembling hand to K. and had him sit down beside her, she spoke with great difficulty, it is hard to understand her, but what she said…”. With these words, Kafka’s acclaimed work The Castle ends mid-sentence, leaving the reader in a suspended state of unfinishedness. The novel was left incomplete when the author died in 1924 at the age of 40 and was destined to be lost forever since Kafka had entrusted his friend Max Brod with his manuscripts asking him to burn them all after his own death. Fortunately for us, Brod recognised their unfathomable literary value and decided to publish, in spite of his friend’s wishes, what would later become Kafka’s most celebrated novels, The Castle included.

When it comes to art, it is a surprisingly high number of uncompleted creative works that, just as Kafka’s novel, are considered masterpieces in their own right; from architecture and poetry to cinema and music, one just has to think of Gaudi’s magnificent Sagrada Familia in Barcelona, Mozart’s Requiem, or the film The Other side of the Wind directed by Orson Welles. In this respect, Fine Art offers plenty of exceptional examples, ranging from the Holy family with Saint John the Baptist (1528-1537) by Perino del Vaga to the portrait of Madame Théodore Gobillard (1869) by Edgar Degas.

Artists from all eras – there are literally cases from antiquity to the present day – have initiated works in a variety of media, later abandoning them for whatever reason, whether historical circumstance, the artist’s sudden demise, the shortage of funding or simply the lack of inspiration or interest in the project. Regardless, unfinished artworks are riveting and intriguing rather by reason of their incompleteness, than in spite of it: they tell a story that was not supposed to be revealed.

Suspended in a state of coming-into-being, they present new perspectives on an artist’s creative process as well as on an artwork’s historical context, even in some cases making unfinishedness a deliberate stylistic choice.

“The revelation of personal sensibility, the quality of the sketch (…) is overlaid and smothered by labour”

Kenneth Clark

Why is Art left unfinished?

Among the varied reasons behind the interruption of an artwork, first and foremost stands the artist’s personality. In this regard, the best example is Renaissance Master Leonardo da Vinci: his perfectionism, combined with his extraordinarily versatile talent, often saw him jump from one project to another leaving an impressive number of works undone in the wake of his impatient striving. In 1550, the artists’ biographer Giorgio Vasari wrote about him: “Marvelous and divine, indeed, was Leonardo the son of Ser Piero da Vinci. In erudition and letters, he would have distinguished himself if he had not been variable and unstable. For he set himself to learn many things, and when he had begun them gave them up. (…). It is clear that Leonardo, through his comprehension of art, began many things and never finished one of them, since it seemed to him that the hand was not able to attain to the perfection of art in carrying out the things which he imagined”.

In 1481, Leonardo was given the commission by the Augustinian monks of San Donato in Scopeto in Florence to paint the Adoration of the Magi; he sketched a few studies and began the project. However, not even one year later, he decided to offer his services to Duke of Milan Ludovico Sforza, following him to Milan and consequently abandoning the piece.

The large life-size draft he left unfinished perfectly exemplifies how incompleteness proves to be a valuable tool for professionals such as art historians, conservators, and curators to get a glimpse of the creative practice. From the delicate underdrawing to the first layers of paint, the work reveals all steps of the art-in-the-making. The artist seems to have repeatedly intervened in outlining the two hundred figures in the complex composition trying to find a balance, to the point that one can almost picture him in his studio obsessively working on the piece until the ultimate decision of abandoning it in favour of a more enticing occasion.

On this theme, Kelly Baum, curator of the exhibition Unfinished: Thoughts Left Visible held in 2016 at The Met Breuer in New York, stated: “An unfinished picture is almost like an X-ray, which allows you to see beyond the surface of the painting to what lies behind: earlier versions, preparatory sketches, all of the underlying architecture which is normally disguised and suppressed. And this gives profound insight into the creative process”.

At times, more tragic events get in the way. Italian Mannerist painter Francesco Maria Mazzola – better known as Parmigianino – as a hopeless perfectionist, spent several years lingering on the gracefulness of his Madonna with the Long Neck, so much so that he died in 1540 before completing the painting. After careful consideration, the patron decided to place the altarpiece in the church it had been intended for; and in the process of doing so, instructed the addition of the following inscription as an explanation for its incompleteness: “Adverse destiny prevented Francesco Mazzola from Parma from completing this work”.

Similarly, though centuries apart, Austrian symbolist painter Gustav Klimt died of pneumonia due to the 1918 Spanish flu, leaving a large number of unfinished paintings. Among these, The Bride – most likely the artist’s most expressionist painting – shows how the artist used to work directly on a bare canvas section by section. Whilst the left area presents highly-refined faces and ornaments, the right one reveals an expressive and energetic sketch, also unmasking Klimt’s technique of depicting naked female figures in detail even though ultimately hidden beneath the gorgeous patterned garments in completed works.

In the case of Take your Son, Sir! by British pre-Rapahaelite painter Ford Madox Brown, the artwork was interrupted by even more poignant circumstances.

Reminiscent of a traditional Madonna and Child, the artist portrayed his wife Emma holding out their baby to the father, who the viewer can see reflected in the mirror as a tribute to the Flemish masterpiece Arnolfini Portrait – that had only recently become part of the collection of The National Gallery in London. Unfortunately, Arthur died at only 10 months old and Brown, in grief and sorrow, was never able to complete the enigmatic painting, leaving it as a testament to his loss

In a time when figurative painting was in decline, the twentieth century portrait artist Alice Neel realised several examples of art more striking for their unfinishedness. She would often invite strangers to sit for a portrait until one day she met James Hunter and asked him to pose. It was 1965, and American authorities had decided on an increase of forces to send to the war in Vietnam; Hunter had just found out that he had been drafted for service and was required to leave within a week. In the first sitting, Neel painted most of his face and hand roughly sketching the outlines of the rest but Hunter never returned from combat to complete the work. Though unfinished, the piece captured the sadness of Hunter’s countenance and soul, so the artist decided to sign it anyway and display it in her first retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 1974.

Non-Finito: the aesthetic of incompleteness

James Hunter Black Draftee’s emotional power necessarily raises important questions: when is an artwork really finished? And does it need to look finished to be complete and meaningful?

In the case of The Flaying of Marsyas by the great Venetian painter Titian, with its almost expressionistic brushstrokes and so different from the artist’s usual polished style: five centuries have passed, but art critics and historians are still debating whether the painting can be considered finished or not. As a matter of fact, the notion of finished – and consequently of unfinished – has changed over time, along with tastes and trends, making it unclear where to draw the line between the two. From antiquity to modern times, art always strived for the perfect representation; it was only in the late nineteenth century that Impressionists experimented with a more loose and spontaneous technique ultimately marking a change of aesthetic principles. In fact, it was Cézanne who stated: “I have to work constantly but not in order to achieve finish, which only attracts the attention of imbeciles”.

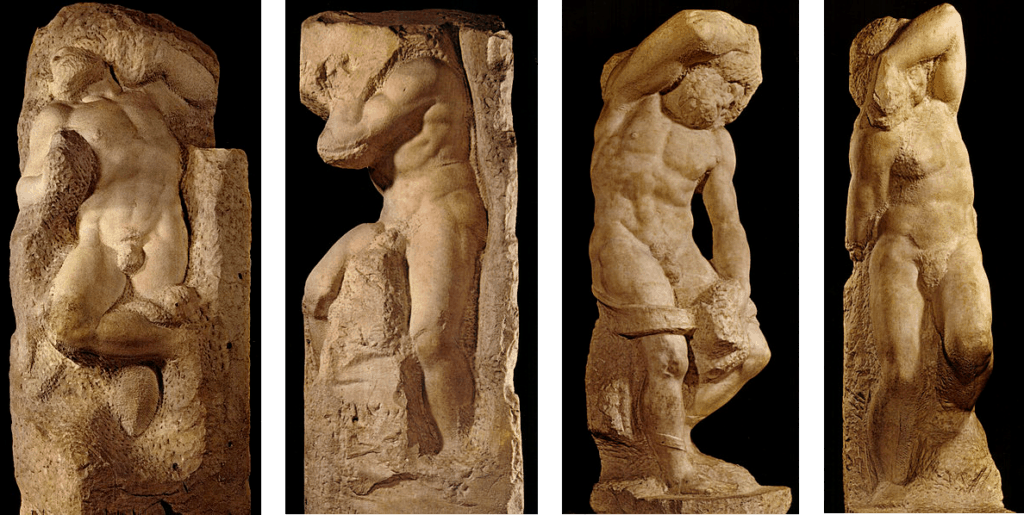

It is therefore surprising that Renaissance Masters such as Donatello, Leonardo, and, above all, Michelangelo with his Slaves – only partially sculpted and appearing to both emerge from and recede into the marble block from which they are hewn – have left us some of the most iconic examples of unfinished art.

These works, though unintentionally, manifested their incompleteness in such a powerful way that they created the cult of unfinishedness, leading other artists to embrace an unresolved look as a deliberate choice. From the effect of incompletion imparted by sculptors like Rodin, Medardo Rosso, and, more recently, Bruce Nauman, to Turner’s sublime depictions of the sea, this style that has come to be known as ‘non-finito‘, intentionally finding in unfinishedness a particular means of expression that is reliant upon the contemplative viewer to infer and complete the picture.

The incomplete state of the non-finito has an enigmatic and compelling characteristic. Whether abandoned, interrupted, or deliberately unresolved, unfinished art always holds an element of fascination.

The Roman author Pliny the Elder, referring to a series of unfinished paintings, argued that “those imperfect works” were “held in greater admiration than the completed pieces, for they display not only the final traces of each artist’s hand but also his very thoughts”.

What is so riveting about unfinished art is that is so close to the human hand and the thought processes that informed it. The fact that artists get bored, lose the spark of inspiration, and simply are subjected to history and the vagaries of fate, renders them relatable and vulnerable, ultimately making unfinished art an oddly intimate matter.

Relevant sources to learn more

Infrared Photography: The Secrets Beneath The Surface