Articles and Features

Hidden Patterns: When Network Science Meets the Art Museum

By Adam Hencz

“What we have been doing really over the last 25 years is challenged by the science and motivated by my interest in art. We ended up systematically developing the language of network visualization.”

Albert-László Barabási for the Northeastern

How does science end up in a museum of contemporary art? Collaborations between science and the arts have a long history, and today visual artists investigate scientific data through the lens of artistic practice as well as scientists draw on interdisciplinary tools bringing the spirit of scientific thinking closer to the world of art and to a broader audience. Albert-László Barabási is one of these humanistic scientists, a physicist and researcher, whose breakthroughs in network science went hand-in-hand with developing an aesthetic language for the portrayal of scientific findings.

Albert-László Barabási’s Network Visualizations

At the center of Barabási’s recent research lies the 3D depiction of invisible patterns and networks that are part of the underlying fabric that hold nature, society and culture together, including the art scene. A recent exhibition at the Ludwig Museum in Budapest was dedicated to the past 25 years of research by the BarabásiLab, a science lab led by Barabási, exploring the development of the language of network visualization, from two-dimensional images created in the mid90s to today’s immersive techniques using augmented reality combined with 3D printing technology.

Photo: Dániel Végel © Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art Budapest

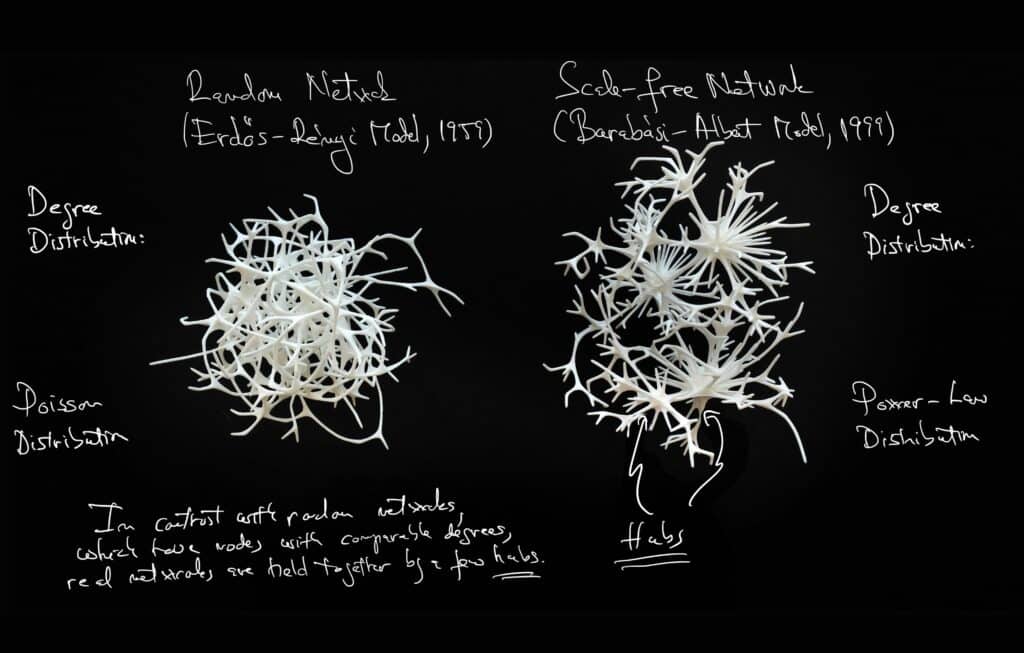

Albert-László Barabási is a Romanian-born Hungarian-American university professor and physicist. He studied physics in Bucharest and then in Budapest, and in 1994 received his doctorate from Boston University. His work led to the recognition of scale-independent networks in 1999, creating the Barabási-Albert model, which describes the structure of the World Wide Web as well as complex metabolic and genetic systems. He is a member of the American Physical Society, an external member of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences and Academia Europaea. His first major book entitled Linked: The New Science of Networks (2002) has been translated into fifteen languages. His newest book The Formula: The Universal Laws of Success from 2020 aimes to uncover what success in our contemporary society really is.

Barabási created his first data visualization in 1995 when, as a researcher working for IBM’s Watson Research Center, he first encountered the concept of network and became curious about how networks are present in everyday arenas and how they support our livelihood in every aspect: from social to professional networks, through infrastructure, transportation and communication. Unconventionally, the first product of his journey as a network scientist was not a research paper, a theorem or an algorithm, but an image instead. His first illustration was a combination of straight black and red links, laid out as a square lattice, in a way that physicists at that time imagined how networks should look like. As the son of a museum chief and a theatre director, Barabási originally wanted to study sculpture and painting, not to become a scientist, thus developing a graphic language to express research findings both aesthetically and in an informative manner became an inevitable device for his scientific thinking. His inclination to combine conceptual art with technical progress shares the essence of the works by prominent members of scientifically based art movements such as Constructivism, Bauhaus, and De Stijl.

During his journey tapping into unknown territories of the concept of networks and translating aesthetic questions into scientific language, Barabási formed the BarabásiLab, an institution engaging physicists, biologists and computer scientists in their pursuit to understand networks and complexity. However, as the visualization challenges have taken a central role in the lab in the past decade, Barabási started to embed designers within the science teams to understand the data behind the phenomena and systems in question and help bring out patterns behind them. Their first network visualizations took shape in two dimensions and looked simple at first glance: circular nodes connected by straight links, with the node colour carrying underlying information about the node identity. That language evolved very fast, through colouring the links, varying the node sizes and curving the links to avoid the dense areas and to provide more visibility of the networks themselves. However, it was only in 2018 that the visualizations stepped out of two dimensions, and Barabási’s Lab started producing 3D printed networks, what he calls ‘data sculptures’.

At the Ludwig Museum in Budapest, the Lab featured its first virtual reality application as well, which is applicable for very large networks that are too big and too detailed to be printed, making it possible for the audience to immerse themselves in them using a headset. “The natural space in which a network wants to exist out there in the three-dimensional space,” Barabási explained in a panel discussion. “Each network has a space in which it wants to exist, and our role as scientists through algorithms is to find that state. The network thinking that my Lab brings along is fundamentally essential to the way we think about art because value and evaluation in the art world are generated by a complex network of curators, artists, artworks, institutions, art critics, collectors and eventually art lovers.”

Hidden Patterns

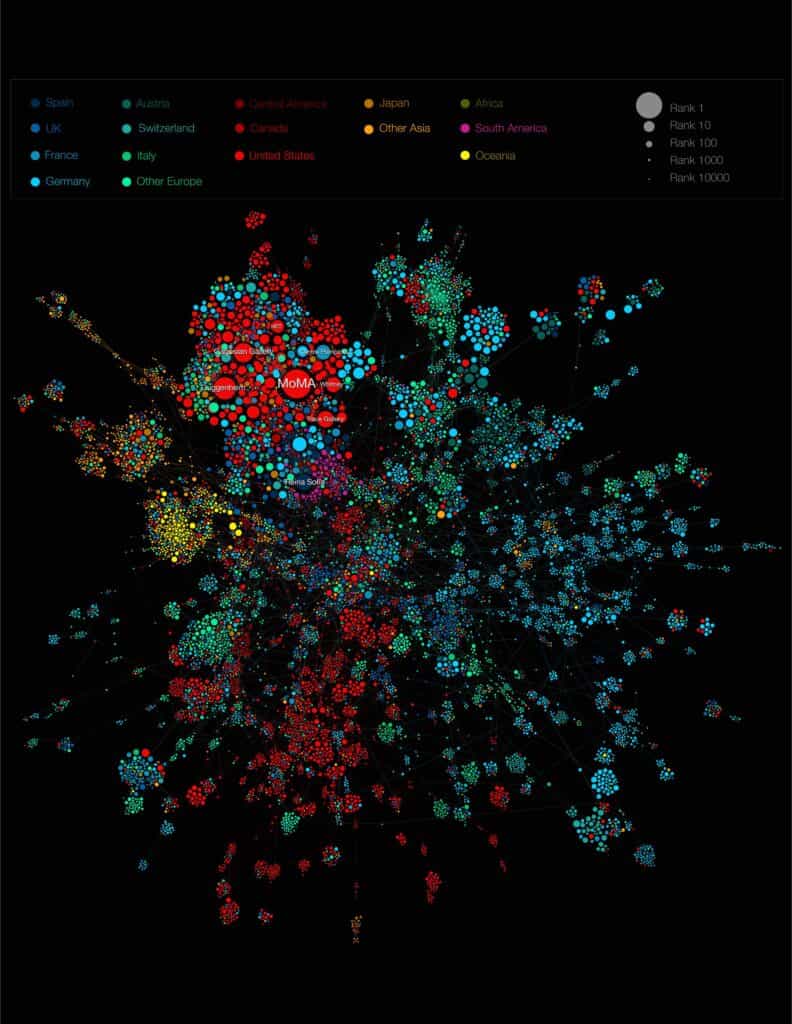

After exploring territories like molecular gastronomy, mapping the disease network and social systems, unveiling the scientific principles that drive success and many other groundbreaking combinations of the field of science, in the past five years Barabási began turning the tools of networks and big data on the art world. He started with a massive number of data points about the exhibition history of half a million artists in galleries and museums worldwide that had been collected by Magnus Resch, an entrepreneur who studies the art market. These data enabled the BarabásiLab to unveil the invisible connections that shape artists’ careers. In The Art Network graph, two institutions (for example a museum or a gallery) were connected if an artist’s work was exhibited in both spaces, thus capturing the largely invisible network of influence and trust between thousands of institutions worldwide and demonstrating how institutional prestige and hidden connections of influence determine access to opportunities for artists.

Albert-László Barabási spends most of his time in Boston, where he is the Robert Gray Dodge Professor of Network Science at Northeastern University. He is the author of Network Science (Cambridge, 2016), Linked (Penguin, 2002), and Bursts (Dutton, 2010), contributing to making networks the revolutionary science of the 21st century.

The retrospective exhibition of the BarabásiLab’s work was created by the Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art in Budapest in collaboration with the ZKM Karlsruhe museum in Karlsruhe, Germany. Following the presentation in Budapest, the exhibition is currently on view at ZKM until January 16, 2022. In the meantime, the exhibition can be explored virtually from when it was at the Ludwig Museum and a catalogue is also available published by Hatje Cantz.

Relevant sources to learn more

Explore the BarabásiLab‘s project archive or watch the panel discussion of Serpentine Creative Director Hans Ulrich Obrist and Albert-Lászlo Barabási on how network effects and big data are poised to shift our understanding of the dynamics of the contemporary art world.