Articles and Features · By Shira Wolfe

Robert Frank. Unseen at C/O Berlin

“That crazy feeling in America when the sun is hot on the streets and music comes out of the jukeboxes or from a nearby funeral, that’s what Robert Frank has captured … and with the agility, mystery, genius, sadness and strange secrecy of a shadow photographing scenes that have never been seen before on film.” Jack Kerouac

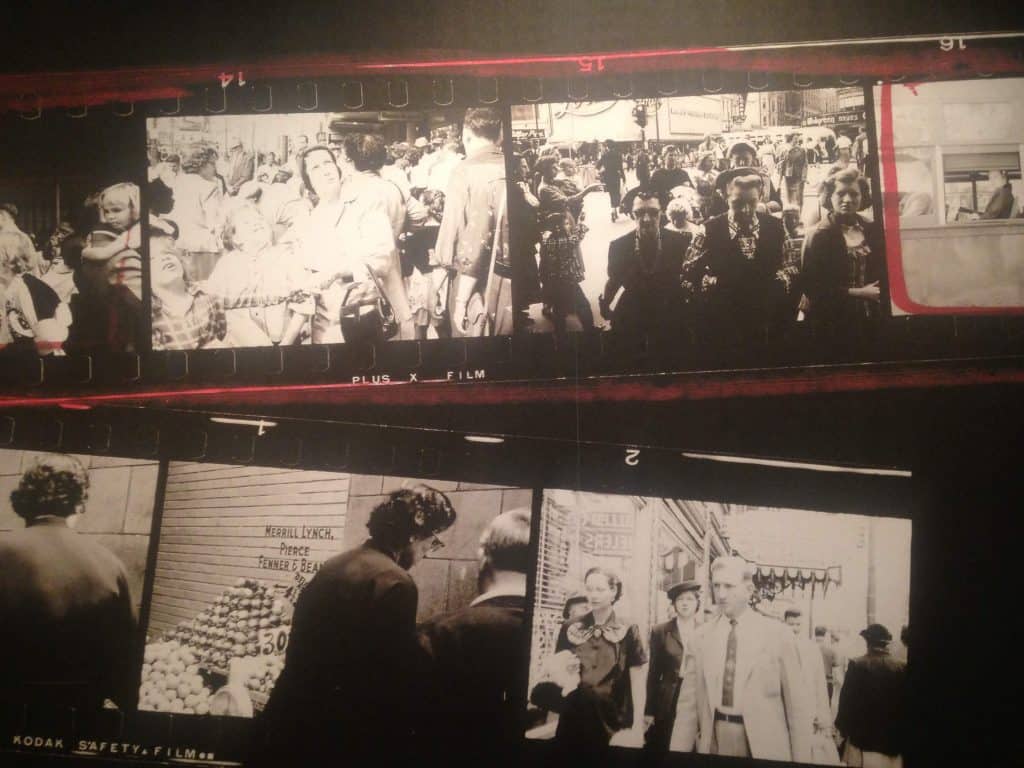

60 years after The Americans, arguably one of the most influential photography collections of all time, was first published, C/O Berlin presents Robert Frank. Unseen. The exhibition offers a unique overview of the photographs of Robert Frank, not just the iconic photographs from The Americans, but also previously unpublished photographs taken during his travels in Europe and South America. Additionally, the 2015 documentary Don’t Blink – Robert Frank by Laura Israel is screened throughout the exhibition’s cycle. One of the highlights of the exhibition is without a doubt the selection of contact sheets on display. These show Frank’s original markings as he was making the final selection for The Americans and reveal the many excellent photographs which never made it into the book but which are often equally strong.

Collection, Winterthur, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and C/O Berlin

Robert Frank’s Angles and Movements

Born in Zurich in 1924, Robert Frank arrived in New York in 1947, where he started working at Harper’s Bazaar photo studio. For several years, he often travelled between the United States and Europe for work, capturing images in New York, Paris, London and Spain ranging from bullfights to people in the financial district, objects in cities and street views. These photographs fill the first few gallery spaces of the exhibition, along with a selection of pictures he took on his travels in South America, after having quit his job at Harper’s to have more freedom in his work.

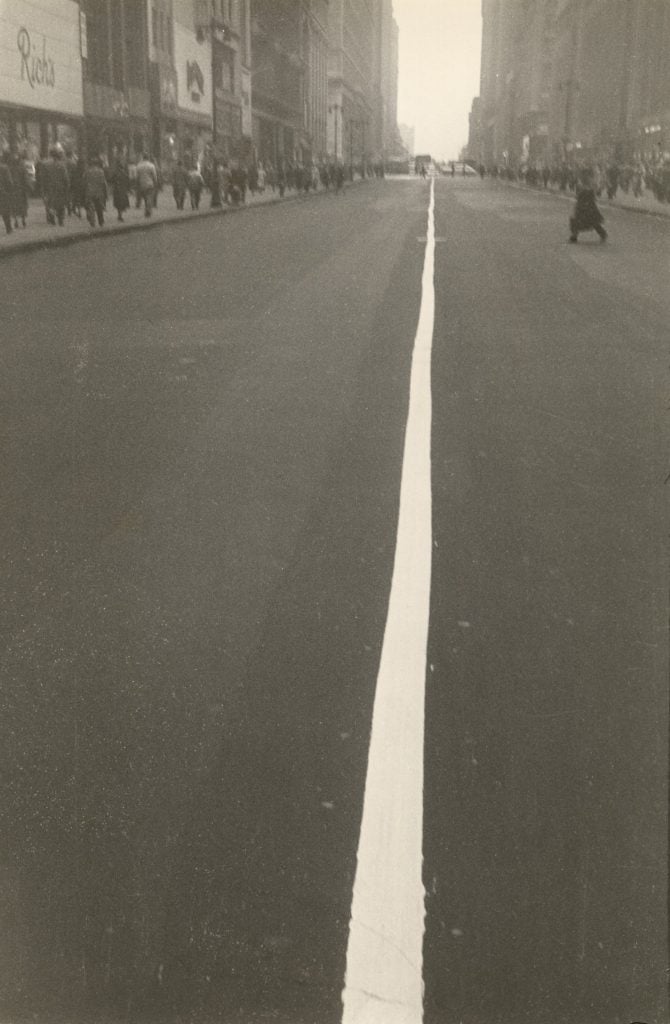

An unforgettable picture is that of a street in New York, taken from such an angle that the street almost completely engulfs the image which is led forward by the street’s white dividing line leading to the small white horizon clamped between buildings on either side.

Frank, who was a technically skilled photographer, described how he worked more and more free from constraints after quitting Harper’s Bazaar. Travelling in Peru and Bolivia, he started using the camera more freely. “I didn’t think of what would be the correct thing to do; I did what I felt good doing, I was like an action painter,” he said. This philosophy carried on into all the work he did, and can be seen in the unusual angle in this New York street photograph, and Frank’s The Americans series. Strange angles, blurred movement, and cropped figures would become his trademark, influencing countless photographers after him.

Collection, Winterthur, Pace/MacGill Gallery, New York and C/O Berlin

“Above all, I know that life for a photographer cannot be a matter of indifference. Opinion often consists of a kind of criticism. But criticism can come out of love. It is important to see what is invisible to others.” – Robert Frank

The Americans

When he embarked on his journey across country, Robert Frank, a Jewish-Swiss immigrant living in the United States, was looking to capture the faces, objects and moments of America. What he discovered and uncovered were arresting images that were seen by some as an attack on their country. The photographs contain dark elements of society, at times picking up on racism, patriotism, corruption and commodified cheer, all hiding behind the façade of American society. But Frank understood the importance of a critical eye. In his words: “Above all, I know that life for a photographer cannot be a matter of indifference. Opinion often consists of a kind of criticism. But criticism can come out of love. It is important to see what is invisible to others.”

Focusing on the everyday, the fleeting and the marginal, Frank crisscrossed the United States, working spontaneously. Photographing intuitively, he was able to capture moments that would never be possible with well-thought-through, technical set-ups. During his cross-country road trip, he took almost 30,000 photographs on over 600 rolls of film. Only 83 made it into his final publication, but his contact sheets on display in the exhibition reveal an incredible amount of works that just add to the window into the different layers of America.

Highlights are Frank’s exteriors and interiors of buildings, diners and petrol stations that can only be found in America, that specific look that is so typical of 1950s on-the-road America. The strongest photograph in this series is Nevada (1956). A small roadside diner, seemingly sad but hopeful in its desolate surroundings, cries out its large-lettered signs to the onlooker: CAFÉ, OPEN, SPARE RIBS, HOME MADE PIES…

In Bar-Gallup, Nouveau-Mexique (1955), we see a scene reminiscent of a Western movie, shot from a low and slightly crooked angle, looking from behind the back of a stranger at what appears to be a staring competition between two bar-goers.

Ranch Market, Hollywood (1956) captures the face of a diner waitress close up, lost in thought in the glaring diner lights, behind her signs promoting deals of the day and an ominous looking Santa Clause sign.

At times, Frank showed moments of silence and contemplation in the midst of city life rolling on all around, even without showing people’s faces. One such image is Yom-Kippur – East River (1955), which shows religious Jews, backs facing the camera, saying their prayers on Yom Kippur by the river. Only the face of a little boy in profile is visible, as he looks calmly out at the river beside the praying men.

Memphis, I Want to Escape is the closing photo-series of the exhibition – four photographs evoking the absolute desolation of the dark, lonely American South. Three pictures of a strangely illuminated roadside building – whether it is an abandoned shed, barn, bar, or house remains unclear – are accompanied by Frank’s musings on this space: “Silence – the Sky turns Dark – no one lives here anymore. I want to escape.” And with these words, Frank invites you to escape with him. It seems like the only real thing left to do.

Forgotten Gems on a Contact Sheet

Choices must be made by the artist, and often this means leaving behind certain pieces in order to create a specific, sharp, coherent picture. Robert Frank’s contact sheets are filled with images that might just as well have made it into The Americans, but for editorial reasons, never did.

The contact sheet with the well-known picture of passengers on a New Orleans trolley, reflecting the times of segregation when black passengers had to sit at the back of the bus, also contains a stunning image of three women in black walking towards the camera on a crowded street. Or the picture of a family in white staring up at the sky, making us wonder what it is they see that all the other passersby in the photograph are missing.

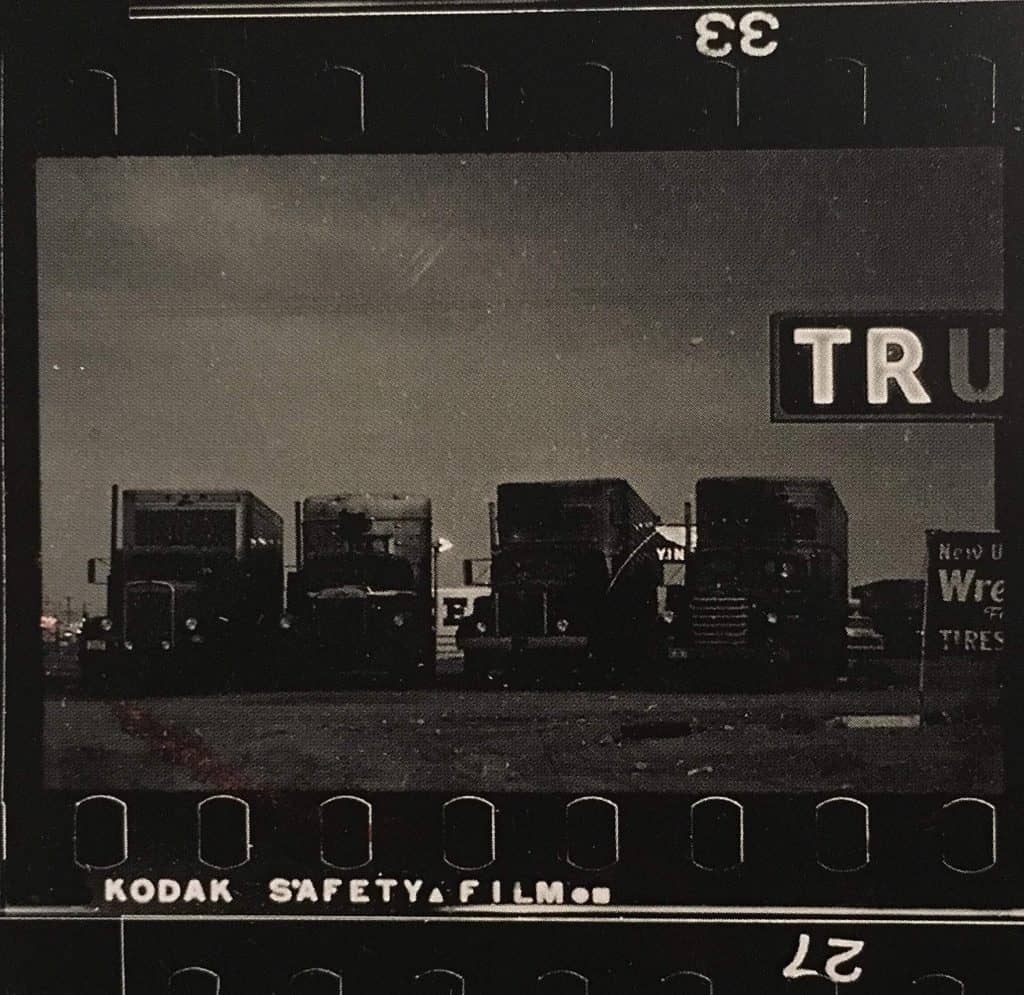

Then there is the haunting image of the truck stop, the letters TRU from TRUCK boldly cut across the right side of the picture, four dark trucks side by side. This picture is from the same series as the Nevada roadside diner photograph, but never made the cut.

All of the deepest layers and stories of Robert Frank’s America are also contained in these unused images. Peering into the small pictures on the old contact sheets, we find on the one hand a world that can never be seen in that way again, and on the other hand a world filled with familiar expressions, objects and feelings that together make up the human condition.

Do not miss a chance to see this stellar exhibition at C/O in Berlin. Robert Frank. Unseen runs through 30 November 2019.

Relevant sources to learn more

Top 10 American Photographers of the American Experience – Artland Magazine