Articles and Features

Stories of Iconic Artworks: Joseph Beuys’ I Like America and America Likes Me

By Shira Wolfe

“Every human being is an artist, a freedom being, called to participate in transforming and reshaping the conditions, thinking and structures that shape and inform our lives.”

Joseph Beuys

All works of art carry a very specific, personal story about how they came to be. Artland’s Stories of Iconic Artworks series delves into the stories behind some of the most iconic works of art ever made. What were the conditions that contributed to the creation of the work, what was the artist experiencing at the time, and what was being transmitted? This week, we will dive into the depths of a performance piece that was among the most radical works of its time: I Like America and America Likes me (1974) by Joseph Beuys.

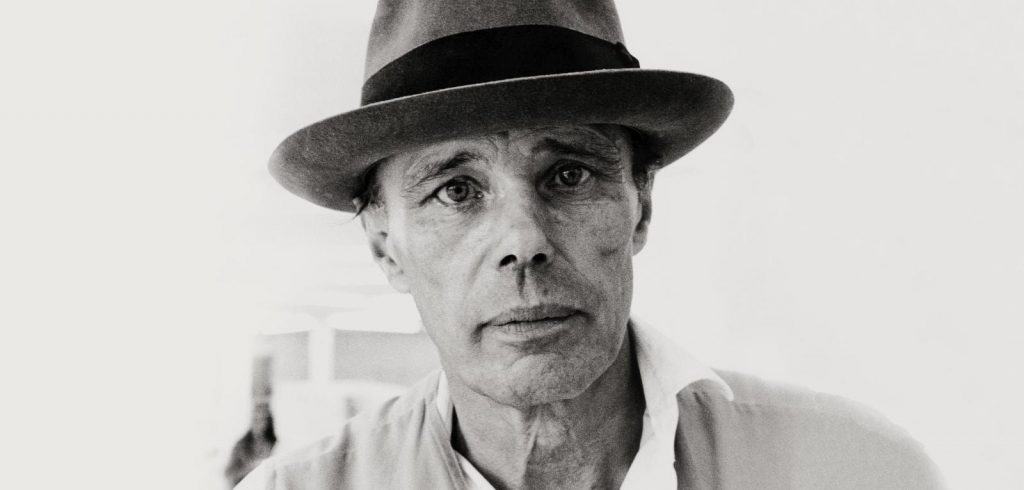

Introducing Joseph Beuys

By the time of this 1974 “social sculpture”, as Beuys called it, he was widely regarded as one of Germany’s most well known and provocative artists. His work often included felt and animal fat, supposedly owing to the fact that when he was a German fighter pilot in 1944, his plane had crashed in the Crimea, and a nomadic Tatar tribesman had found him and wrapped him in animal fat to insulate him. Beuys used felt and animal fat as shamanic tools, with which he attempted to heal and regenerate the wounds in society through artistic gestures and communication. With his so-called “social sculptures,” Beuys aimed at improving society. It was his philosophy that everybody is an artist, who has the potential to change the world around them. Beuys believed that teaching was his greatest work of art, and brought his philosophy on art into the classroom by abolishing all entry requirements to his class at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf. He also encouraged his students to explore their own interests and ideas, and was very careful not to impose his own artistic style or techniques on his students.

Beuys’ first solo exhibition in a private gallery took place in 1965, and became one of his most famous performances: How to Explain Pictures to a Dead Hare. His face covered in honey and gold leaf, an iron slab attached to his boot, and a dead hare cradled in his arms – these were the core elements of the performance piece. In line with his great pedagogical aspirations and beliefs, he spent the performance mumbling explanations of the drawings lining the walls into the ears of the dead hare.

Joseph Beuys and the Coyote

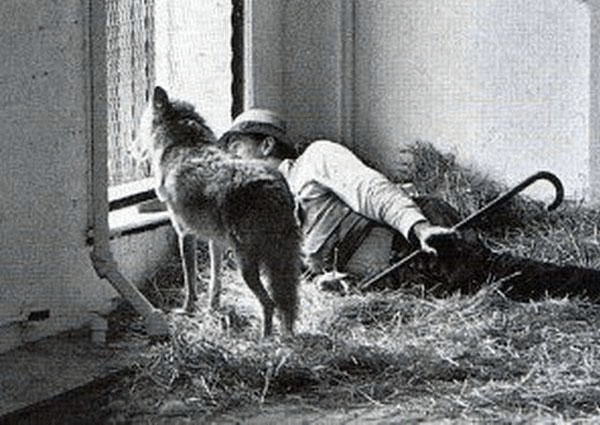

It was 1974 when Beuys arrived in New York City, ready to tackle a whole new challenge and create what was to become one of the most famous works of art of the time. Upon arrival, his assistants wrapped him in a large piece of felt and transported him, by ambulance, to the René Block Gallery in SoHo. There, awaiting the artist, was a live coyote. Beuys spent three consecutive days, eight hours at a time, locked up with the wild animal. He sat or stood, wrapped from head to toe in his large felt cover and held a crooked staff, peeking out from the top of the felt.

Props accompanying him in the cage included heaps of straw, a pile of copies of The Wall Street Journal of the day and a raggedy old hat from the best hat shop in London. Then, of course, there was his co-star, the coyote.

Beuys’ idea behind I Like America, and America Likes Me was to start a national dialogue. America in the 1970s, caught in the horrors of the Vietnam war, and divided by oppression of minorities, the indigenous population and immigrants, was far from the welcoming American Dream that the title of this performance suggests. The coyote symbolised a variety of things for Beuys:

First, there are some Native American myths that suggest that the coyote represents the possibility for transformation, as well as an archetypal trickster. Then, there are certain creation myths in which the coyote teaches human beings how to survive. And while most European settlers and their present-day American descendents generally regarded the coyote as an aggressive and dangerous predator, Beuys saw the animal as something completely different: to him, it was America’s spirit animal.

During the three days of the performance, Beuys attempted to make eye contact with the coyote, while performing symbolic gestures. He would toss his leather gloves at the animal, or wildly gesticulate at it. The coyote, in turn, was mostly curious, at times hostile, and often fairly calm. Once, he tore off a piece of Beuys’ gloves; another time, he tried to rip the felt cover off of Beuys, clenching it firmly in his jaws. But he also allowed Beuys to briefly embrace him. Beuys stayed in direct contact and communication with the coyote up until the very end of his performance. When it was over, he was bundled up again, returned to the ambulance, and driven straight back to the airport. He never once set foot on American soil, except for the gallery space. He wanted the only ground he touched in America to be the ground he shared with the coyote.

With this intense performance, Beuys wanted to demonstrate that American society could only start to heal its social issues through communication, connection and mutual understanding between all of America’s vastly different social groups.

After the Performance

Five years after I Like America, and America Likes Me, Beuys created a piece called News From the Coyote. This piece referred back to the 1974 work, and included mementos from the original piece: the staff, the hat, a strand of his hair and the coyote’s fur, the felt blanket, and the bitten-up gloves. He also added the triangle that he had struck from time to time during the 1974 performance, creating almost sacred sounds. Another element in this 1979 piece was a white powdery hill, which consisted of rubble from the ruins of the René Block Gallery in West Berlin. He also used sulphur and branches with miner’s lamps attached to them. The lamps were meant to symbolise light in dark, difficult places and times.

Beuys’ performance with the coyote remains extremely relevant today, as America seems no closer to healing its deep wounds and closing the rifts between different social and ethnic groups. In fact, with white nationalism, fear-mongering, and racism towards minority groups prevalent not only across the United States, but also in Europe, Beuys’ profoundly moving communication with the wild coyote is a work of art that people can continue to learn from and seek answers and inspiration in. It appears that basic human and animal communication are in desperate need of a revival.

Relevant sources to learn more

For more background information and reflections on Joseph Beuys and his iconic performance piece, explore:

New York Times

See part of the performance here: Vimeo

Read more about Joseph Beuys on Artland: The Other Joseph Beuys: The Drawings of the Myth-Making Action Artist