Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Rose Wylie

“It shouldn’t be about age or gender or anything. It should just be about the quality of the painting. That’s what I’d like to be known for. Paintings. Not because I’m old and the climate has changed and old people are welcomed.”

By Shira Wolfe

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. In this week’s edition, we feature Rose Wylie, the 86-year-old British artist who for years was one of those figures whom the art world knew about, yet didn’t quite know what to do with. In recent years, her work has been the subject of renewed critical acclaim. Yet the artist insists she doesn’t care to be known simply because of this appreciation of her at an older age, now that the art world is becoming more inclusive towards artists of an older generation. Wylie cares about the quality of the work, and it’s a pleasant perk that galleries and museums worldwide finally recognise the quality and relevance of her wild, playful large-scale canvases.

Rose Wylie’s Unconventional Journey in Art

Born in 1934, Rose Wylie studied art at Folkestone and Dover School of Art, Kent in the 1950s. She met her late husband, fellow artist Roy Oxlade, there, and essentially took a break from the art world to raise their family. Wylie returned to study art in her 40s, at the Royal College of Art in London, from which she graduated in 1981. This break, in many ways, held advantages for Wylie. She didn’t have to deal with the constant frustrations and relentlessness of the art world, instead, returning to it at a later, more mature, age, allowing her to work with more energy and persistence.

Wylie’s impressively large works show both a style developed completely independently from art academies, while also at times reflecting her roots there. The composition and references to art history definitely owe a debt to a classical training in art, while her childlike playfulness and spontaneous wildness shows her wide interests in all elements of life around her, from the neighbours across the road to movies she’s seen and articles she’s read.

Wylie was in her 70s when she really made her breakthrough and started to be widely exhibited, sold, and appreciated. Yet she takes these developments with a grain of salt and insists in an interview with The Guardian: “It shouldn’t be about age or gender or anything. It should just be about the quality of the painting. That’s what I’d like to be known for. Paintings. Not because I’m old and the climate has changed and old people are welcomed.”

“I do like big work. I like billboards. I like very early decorated churches where the paintings go from floor to ceiling and up arches and round the door. I’ve always thought it’s a very convenient way of using spaces in galleries and spaces anywhere.”

Rose Wylie’s Style and Large-Scale Philosophy

Rose Wylie works on unstretched canvases, which used to be sprawled on the floor, but are these days pinned to the walls of her studio since following a hip replacement surgery she can no longer squat for long periods. Working like this on unstretched canvases she might repaint parts of her canvases 50 times until she is satisfied. Some bits are collaged, and often, large letters in block script are scrawled across the canvas. Her canvases are almost billboard-sized, magnifying small motifs and everyday inspiration into arresting works of art.

At first glance, Wylie’s works may seen simplistic, but they are really deeply layered works which meditate on the very nature of visual representation, different art forms, popular culture, everyday life and the people she encounters and who fascinate her. The Guardian’s Skye Sherwin likens Wylie’s art to that of Philip Guston and Jean-Michel Basquiat, in the sense that her figures are crudely forged.

Her figures are cartoonish, direct, her compositions colourful and lively. She often explores women’s bodies, creating an open attitude towards looking and seeing, perhaps in the same way that she enjoys people watching – be it her neighbours across the road, or strangers on an escalator. There’s something incredibly anti-pretentious about Wylie’s works that aligns with her wild and free approach to painting.

A Selection of Rose Wylie’s Artworks

In her painting “Lords and Ladies” (2016), which was selected back in 2010 as part of an exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC featuring “underrepresented and/or emerging women artists,” Wylie took inspiration from something she read in The Guardian. Part of the text ended up in her painting: “For better for worse, divorce is always stressful, but…” She painted a bride and a groom, then continued exploring from there, finally adding one of her favourite images, the portrait of Philip IV of Spain by Rodrigo de Villandro (c. 1620).

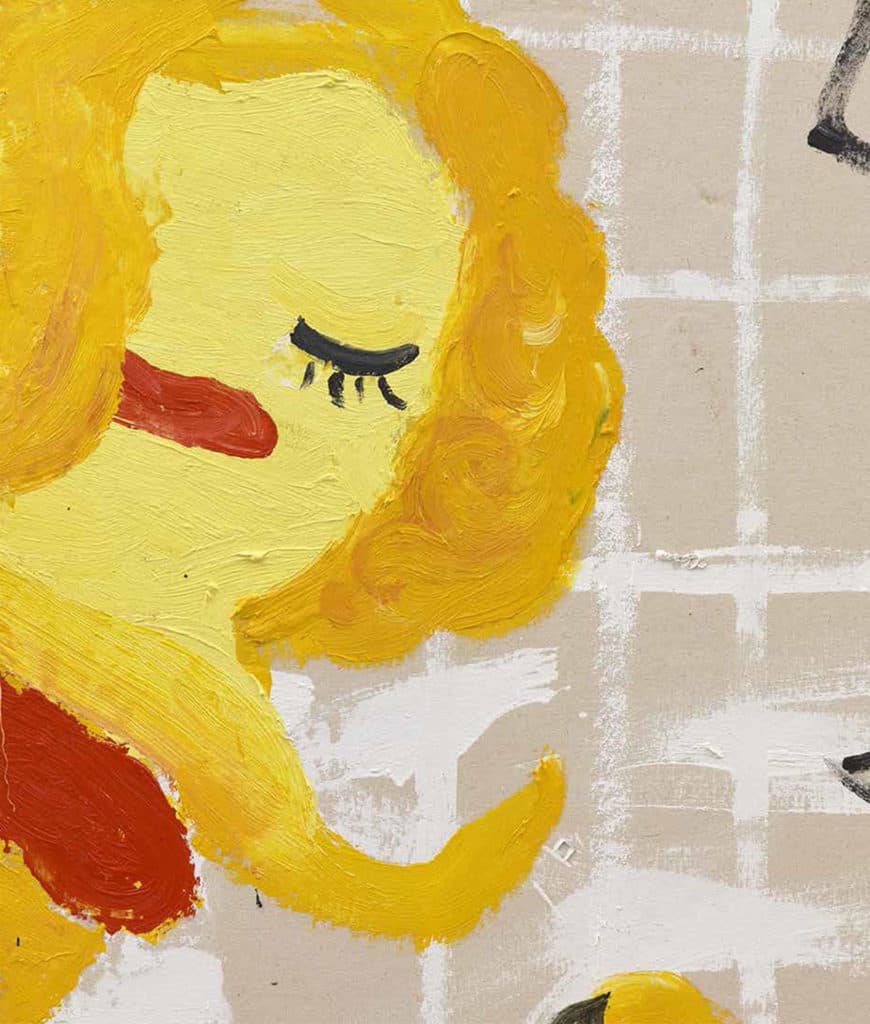

“Yellow, Girls I” (2017) is part of a series loosely referencing a house across the street from Wylie’s Kent home, and the neighbour’s teenage daughter who lived there and would often wash the car in the driveway. The series was exhibited in the 2018 exhibition “Lolita’s House” at David Zwirner, London. In “Yellow, Girls I”, Wylie transposed part of a drawing from her diary onto the canvas. She added the grids of notebook paper, creating a space on which to explore several versions of her Lolita. One of these girls is like a simplified version of a Kirchner girl – skeletal face, dark hair, little red bow in the hair – while another, the larger blonde figure, has more of an exaggerated cartoonish bombshell look.

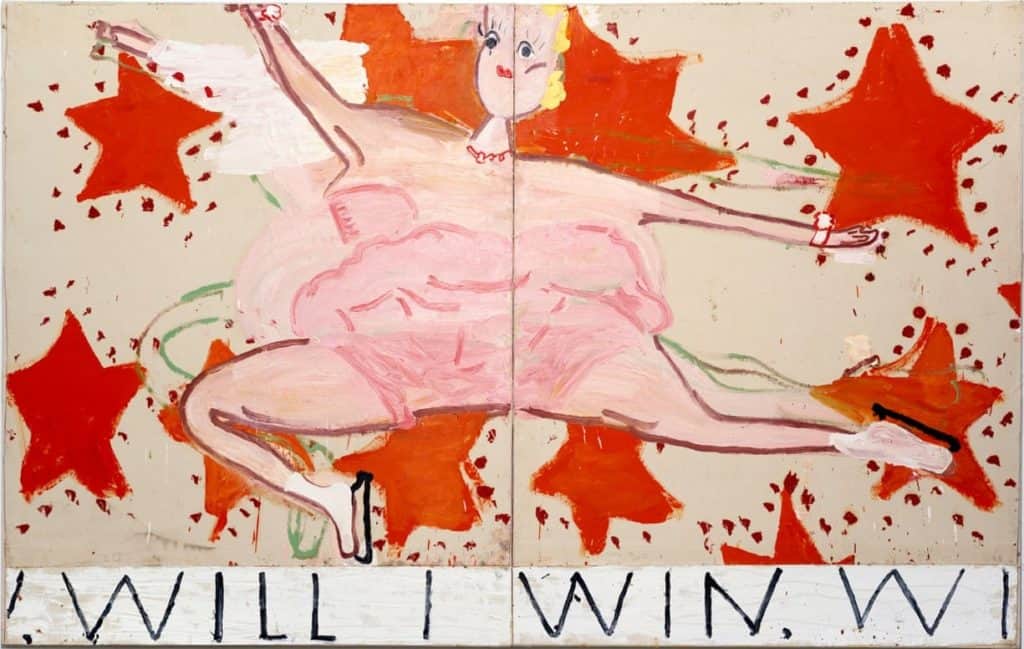

“Pink Skater (Will I Win, Will I Win)” from 2015 shows a female ice skater in a pink costume, leaping in mid-air past vibrant red stars, above the text in large letters “Will I Win, Will I Win”, flashing below her. It’s like a strange excerpt from a TV-show, transposed onto canvas.

Representation and Exhibitions

Attention for Wylie has been growing since 2010, when she was part of the exhibition featuring underrepresented women artists at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, DC. Since then, she’s had several solo exhibitions, including one at the Tate Britain in 2013. She also won the John Moores Painting Prize in 2014, and in 2015 she won the Charles Wollaston Award for a painting which was included in London’s Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition.

Wylie’s first exhibition at David Zwirner in London was held in 2016, and she has been represented by the gallery since 2017. In 2018, she had a solo exhibition at the Serpentine Galleries in London.

Now, David Zwirner Hong Kong is showing Rose Wylie’s works in the artist’s first solo exhibition in Hong Kong: “Rose Wylie – painting a noun…” Running through 22 February 2020, the exhibition will underscore the importance of memory as both a fixed and shifting concept in Wylie’s work.

Along with David Zwirner, Rose Wylie is represented by GNYP Gallery, CHOI&LAGER Gallery, Polígrafa Obra Gráfica, and Thomas Erben Gallery.

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more about Rose Wylie and her artistic practice here:

Rose Wylie is a British artist known for her exuberant, large-scale paintings. She was in her 70s when she was discovered, and has been the subject of countless important solo exhibitions for the past years.

What is Rose Wylie’s Style?

Rose Wylie paints spontaneously, inspired by everyday life, popular culture, the media, as well as art history. She often paints or collages over a certain spot many times until she is satisfied with the result. Her coarsely wrought figures invite an open way of seeing and interpreting people and situations.