Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Jack Whitten

By Shira Wolfe

“Art runs parallel to religion. It’s an act of faith.” – Jack Whitten

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series features artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or largely invisible for most of their career. The last artist we featured was Norman Lewis, the only African American artist to be part of the first generation of Abstract Expressionist artists. This week, we examine the life and work of African American abstract artist Jack Whitten (1939-2018), who is celebrated for his innovative painting processes with which he transfigured the material terrains of his canvases.

The Early Days of Jack Whitten

Jack Whitten was born in 1939 in Bessemer, Alabama, in a time when the American South enforced racial segregation. Whitten described the reality in which he grew up as one of “American Apartheid.” After briefly studying medicine at the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama in the late 1950s, Whitten was drawn to art. He first attended the Southern University in Baton Rouge, and then moved to New York in 1960, where he enrolled at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art and earned his BFA degree. He also immersed himself in city life, frequenting the Cedar Bar, where many of the Abstract Expressionists hung out. It was there that he met Willem de Kooning, who became a friend and an important influence on his career. He also became close friends with Romare Bearden, Norman Lewis and Jacob Lawrence, who were great supporters of Whitten’s art.

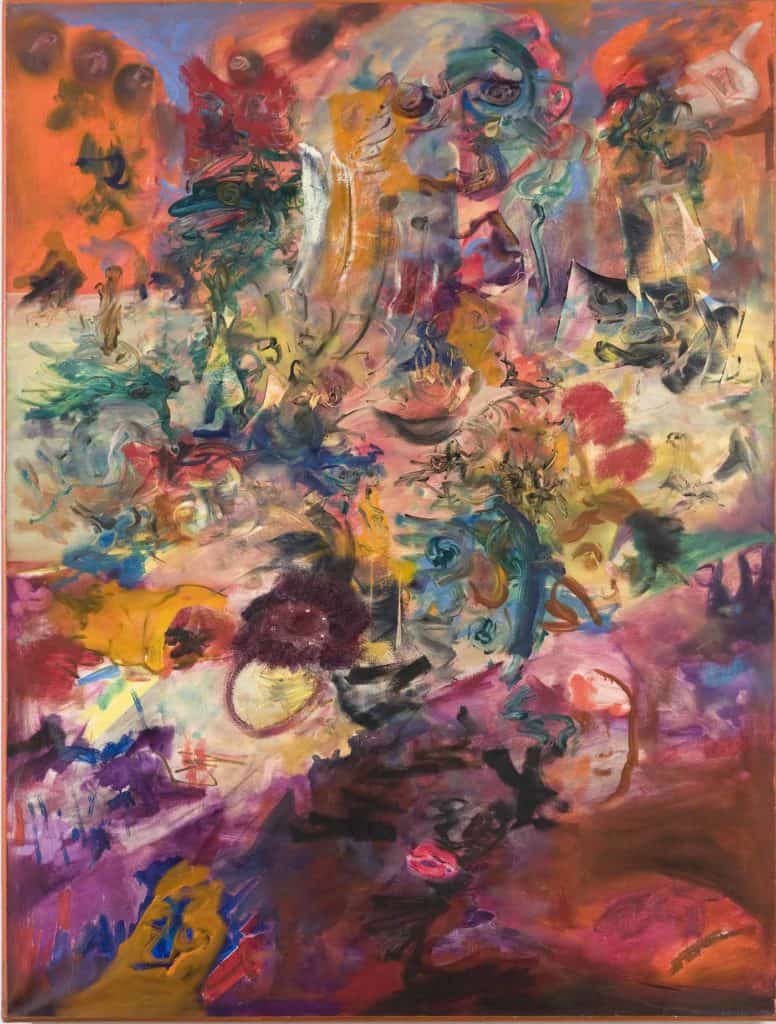

His initial experiments in painting during the 1960s were inspired by Abstract Expressionism and Surrealism. Jazz music also proved to be an important influence on Whitten’s work. He often went to jazz clubs to experience the progressive New York City music scene, and met with musicians the likes of John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Max Roach and Ornette Coleman. Paintings from this period also show his lifelong preoccupation with the Civil Rights Movement, for example his “King’s Wish (Martin Luther’s Dream)” from 1968, a deeply expressive and surreal painting that moves between abstraction and figuration.

While he was initially aligned with the Abstract Expressionists, he gradually distanced himself more and more from the movement’s formal concerns and aesthetic philosophy, and started focusing more intensively on the experimental nature of process and technique. This would come to define his artistic practice.

“I am black, 46 years old, angry, tired of teaching, tired of being poor. […] What am I to do?” – Jack Whitten

Jack Whitten – the 1970s

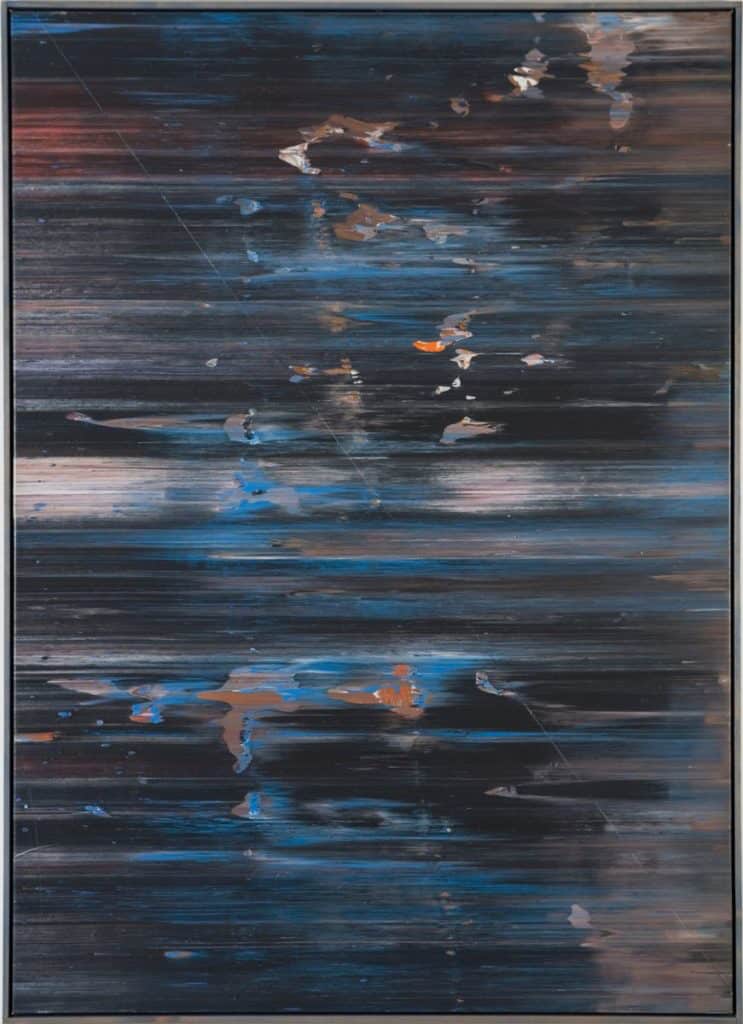

In the 1970s, Whitten’s experimentations in abstraction reached a climax. Whitten started to drag large troughs of paint across the canvas with tools like squeegees, rakes, and Afro combs, creating tangible surface textures. In his notebooks from this period, he wrote: “I’ve done so much. I’ve tried everything. I’ve tried the saw blade, afro comb… To be as clear as possible without becoming confused. I JUST WANT A SLAB OF PAINT.” He eventually developed a new method of painting that more closely resonated with photography. He created an instrument which he called “the developer,” with which he could quickly spread a layer of acrylic paint onto a canvas with a single gesture. This discovery led to the development of his signature slab paintings. With this development, Whitten removed gesture from the process and challenged pre-existing notions of dimensionality in painting.

Back to Zero – A New Direction

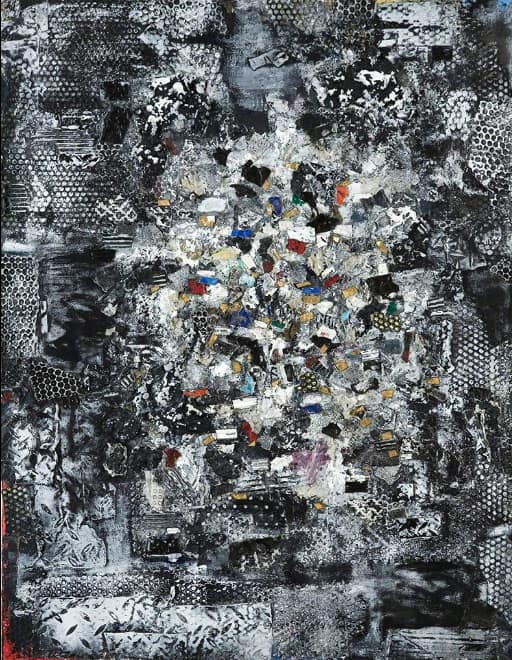

By the 1980s, the physical demands of working with his developer tool were taking a toll on Whitten’s body, which led to a new experimentation with acrylic paints. He experimented with “casting” acrylic paints and compounds to create new surfaces and textures. As such, painting became a metaphor for skin. Whitten’s artworks, contrasting a great deal with the narrative-based and didactic works made by many of his peers during this period, were all about reintroducing gesture with aspects of sculpture and collage. His self-portraits from the period express his existential dealings with life and work. Working from a point of abstraction, he started heading towards image. Balancing financial pressure with his great need to push boundaries in his work, Whitten experienced a period of immense self-doubt, writing in his journal: “I am back to zero. The only thing I have to salvage from the past fifteen years is the fact of the hard backing; the bringing of the floor up to the wall. This is meaningful. I want to start 1986 with a clean slate. Of course, this destroys any chance of getting a gallery, no one is interested in an artist at the end of a series and beginning a completely unknown beginning. I am black, 46 years old, angry, tired of teaching, tired of being poor. […] What am I to do?”

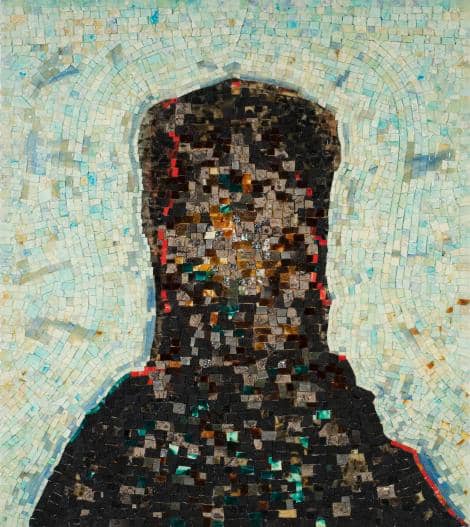

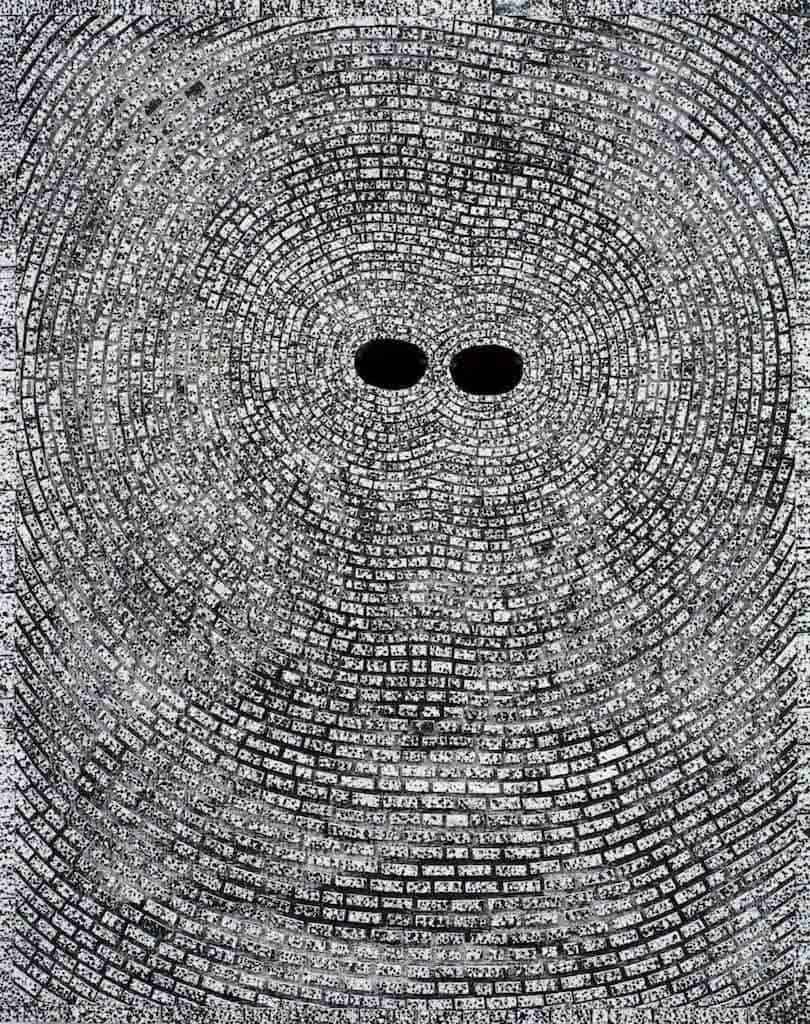

Exploring Mosaic

Since the 1990s, Whitten’s experiments with paint as a medium progressed further in the direction of sculpture. He started transforming paint compounds into tiles, and applying them to the canvas as mosaics. With these pieces, Whitten hinted at ancient architecture and murals. They also served as a homage, or memorial, to intimate friends and celebrated public figures. This was an important conceptual shift for Whitten, bridging the gap between traditional brushwork and contemporary applications of paint. Inspired by the light properties in each individual paint chip, he would allow the refractions from one piece direct his placement of the next. This discovery gave Whitten the artistic freedom he had been searching for. “If I let go and follow the light,” the artist wrote in a journal entry from this period, “the world is my oyster!”

The Legacy of Jack Whitten

It took a long time for Jack Whitten to be widely appreciated and celebrated for all of his accomplishments, but the art world is finally catching up. Jack Whitten passed away in 2018, and leaves behind a considerable legacy. Between 2007-2015 he was represented by Alexander Gray Associates, and his estate is currently represented by Hauser & Wirth. Until 1 September 2019, Whitten’s works were on view in a major retrospective at the Hamburger Bahnhof Museum in Berlin, titled Jack’s Jacks. This was the first-ever solo show of the artist in a European museum. Whitten’s body of “memorial paintings” formed the core of the exhibition. Since the beginning of his career, Whitten dedicated his paintings to friends, family or important public figures. He considered these a type of gifts for the people he mentioned in the titles. Paintings are dedicated to people such as Norman Lewis, Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol, Louise Bourgeois, Robert Rauschenberg, Arshile Gorky, Martin Luther King, Barack Obama, Duke Ellington and John Coltrane.

Currently, Hauser & Wirth is presenting an exhibition of Whitten’s works in New York. The exhibition, which runs till 4 April 2020, is titled “Jack Whitten Transitional Space – A Drawing Survey.” This is the first major survey of Jack Whitten’s works on paper.

Photo: John Berens. Courtesy The Estate of Jack Whitten and Hauser & Wirth.