Articles and Features

Lost (and Found) Artist Series: Ming Smith

By Shira Wolfe

“Being the first black woman photographer to have a work acquired by the MoMA was like getting an Academy Award and no one knowing about it.” – Ming Smith

Artland’s Lost (and Found) Artist Series focuses on artists who were originally omitted from the mainstream art canon or who have been largely overlooked for most of their careers. This week, we explore the stunning photography of Ming Smith, who in 1975, was the first black woman photographer to have a work acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

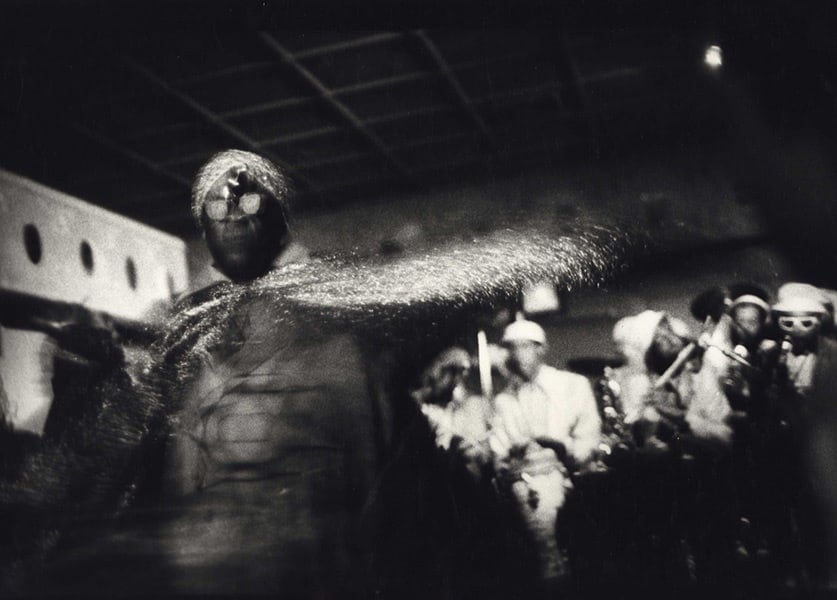

Ming Smith – Photographing Black Culture

Ming Smith was born in Detroit in the 1950s, and grew up in Columbus, Ohio. Though she started out studying medicine at Howard University in Washington, DC, she soon switched to microbiology. Her marriage to jazz musician David Murray meant that she spent a lot of time on the road touring with various jazz performers. She brought her camera along and started taking impromptu photographs of the jazz musicians, as well as different elements of black culture. She was passionate about capturing the love and richness of black culture, but said in a 2019 interview with the Financial Times that “[b]eing a black woman photographer was like being nobody.” At the time, she didn’t think it was even possible to make money from her photography, let alone to receive any recognition through exhibitions of her work. When she moved to New York, she started out with a career as a fashion model, allowing her to meet the expenses arising from her growing interest in photography.

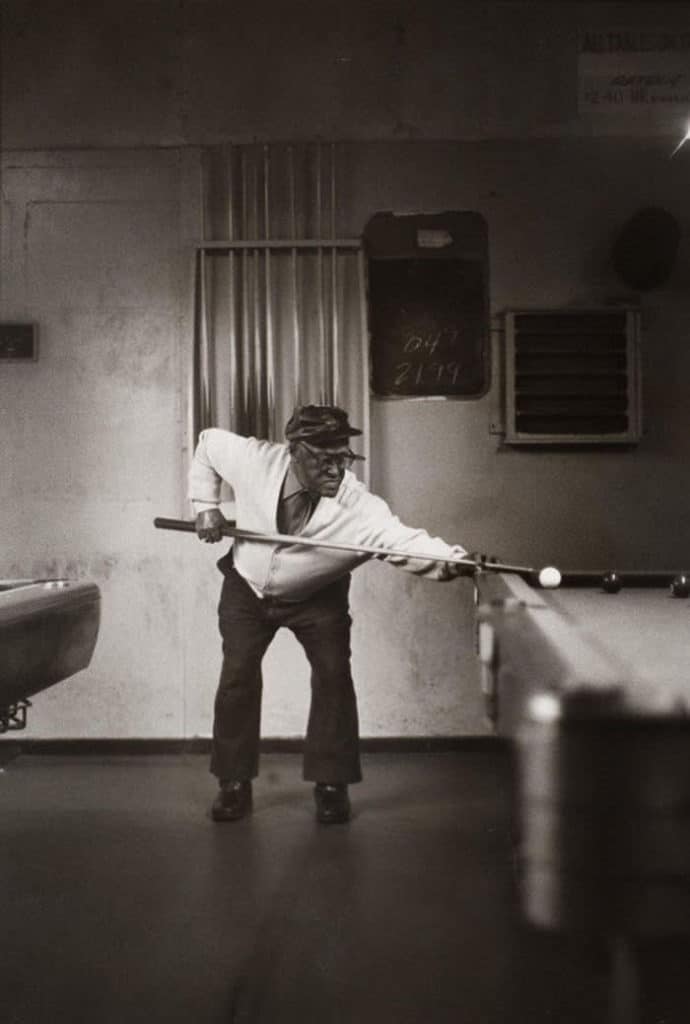

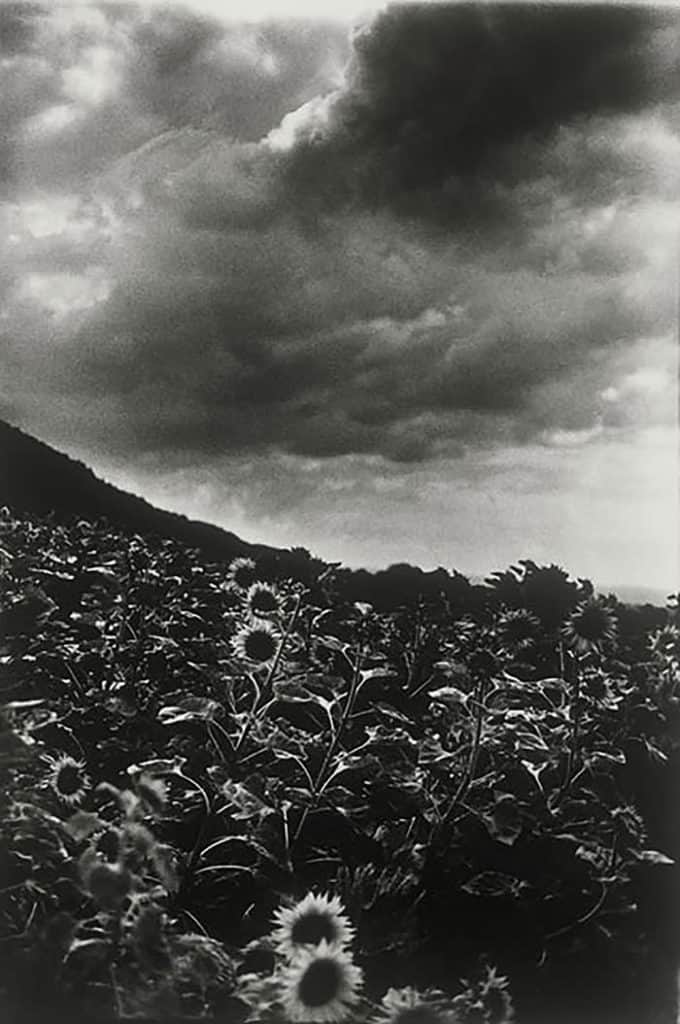

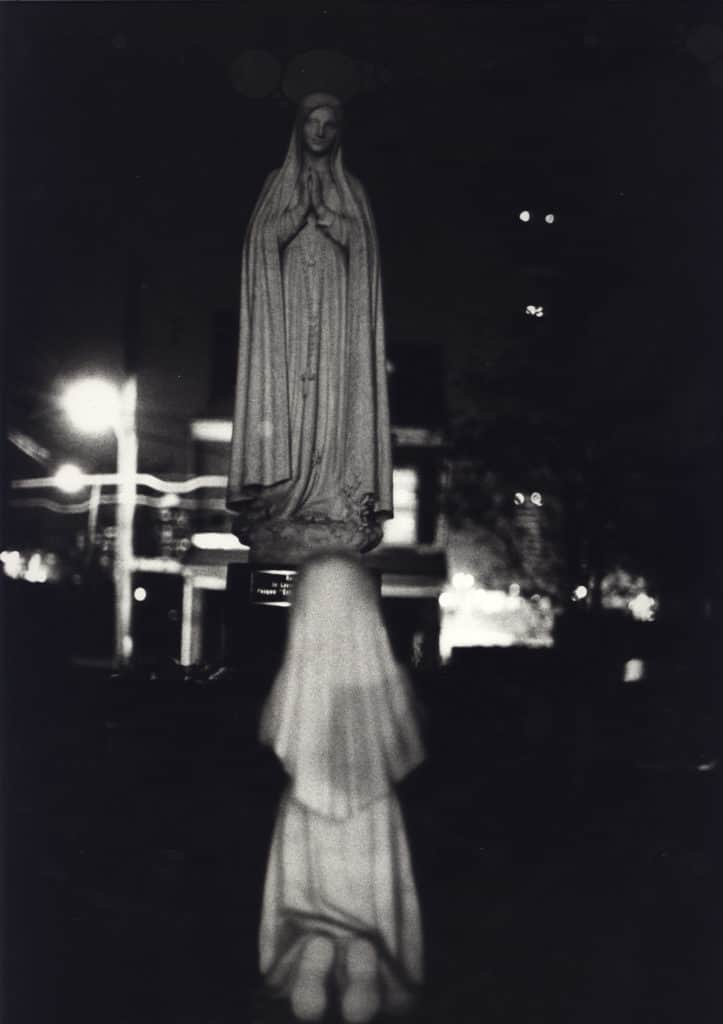

Ming Smith’s Style and Subjects

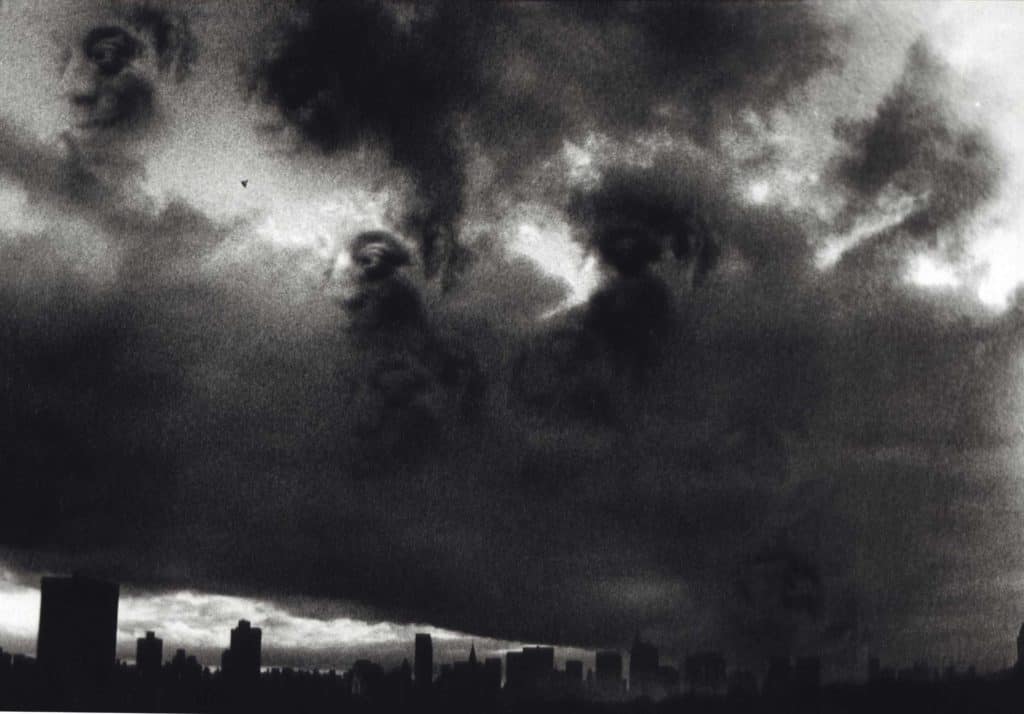

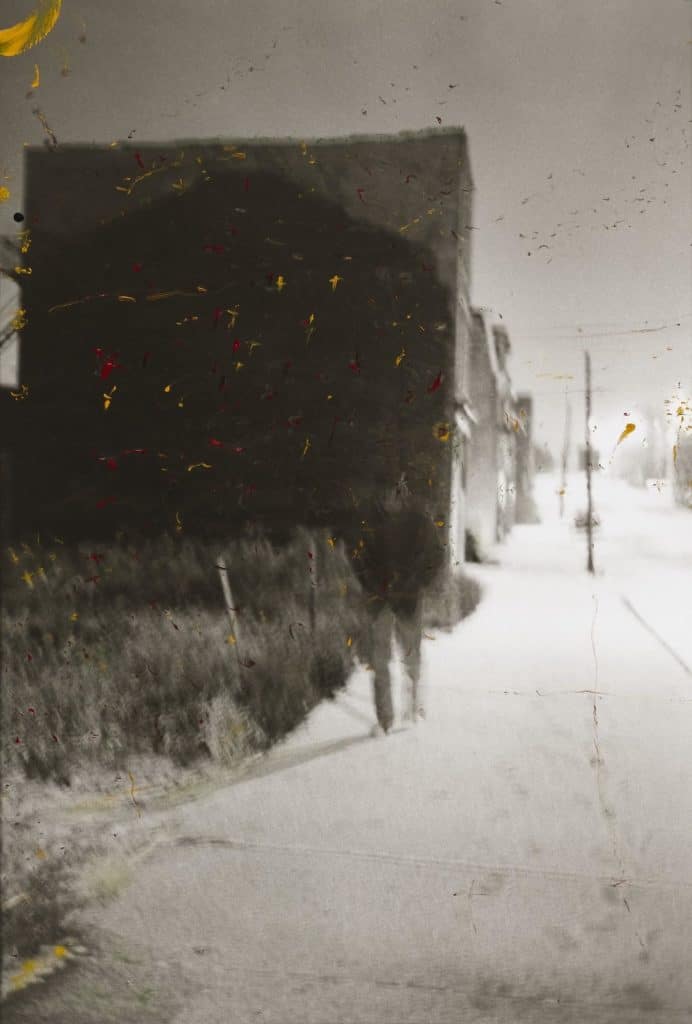

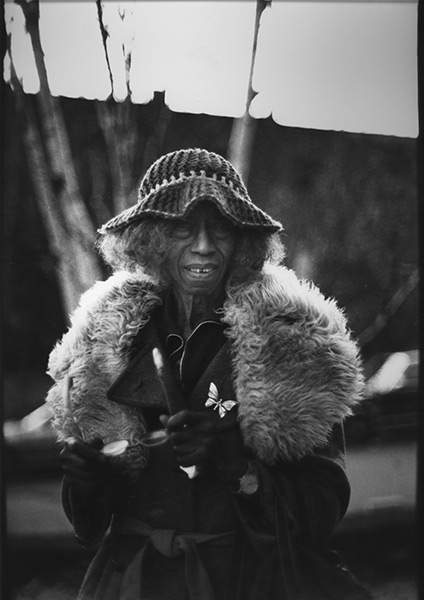

From early on, Smith’s style could be characterised as fast-shooting with a rigorous developing and post-printing process, producing complicated and elaborate images with an ethereal quality. Her shooting style often results in out-of-focus images, obscuring the finer details of figure and background. Through this deliberate blur, Smith creates a semi-abstract effect, making her works immediately recognisable but also giving them a unique, dream-like quality. This quality is enhanced by Smith’s experimental post-production techniques which include double-exposure, collage, and painting on prints. Smith’s personal visual language of light and shadow lends a timeless nature to fleeting moments in time. In the words of fellow photographer Gordon Parks, Smith’s “wondrous imagery… gives eternal life to things that might well have been forgotten.”

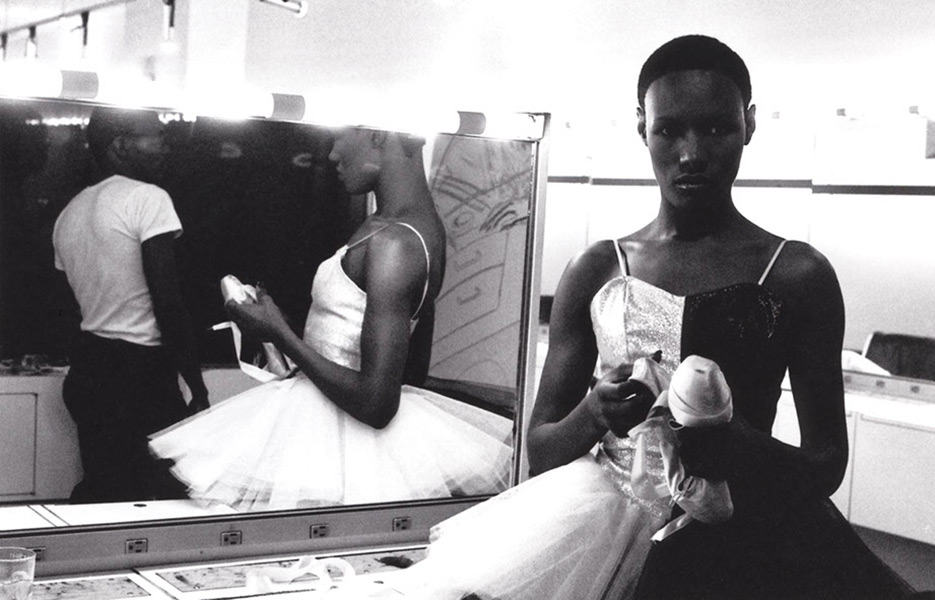

Smith’s subjects range from artistic, literary and musical icons including James Baldwin, James van der Zee, Romare Bearden, Nina Simone, Tina Turner, Sun Ra and Grace Jones, to anonymous city-dwellers.

Ming Smith’s First Exhibition

Smith had her first exhibition in 1973 at Cinandre, a hairdressing salon on 57th Street and Madison Avenue. She recalls the space as very progressive: “You had black and white, straight and gay. It was artistic and there wasn’t any judgment.” More established African American artists like Romare Bearden and Roy DeCarava came to the exhibition opening, and Cinandre also marked the beginning of a friendship between Smith and Grace Jones, who would come to the salon to get her hair done. Smith and Jones would talk about their everyday life struggles trying to make it in the city, trying to make money, trying to survive. Both women had grown up under Jim Crow’s laws, so it was a huge step for them to have come to New York, trying to forge careers as models and artists. In 1975, Smith took a striking photograph of Jones wearing a black-and-white tutu in a dressing room. She captured a look of deep determination mixed with a gentle vulnerability, a look shared between close friends.

© Ming Smith, Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery

Kamoinge

Around the same time as her first exhibition, Smith was invited by Anthony Barboza and Lou Draper to join the Harlem-based photography collective Kamoinge, a collective which included people like Roy DeCarava and Gordon Parks. She was the first woman to join the collective, but never worried about her gender in the all-men group. The most important thing was that they were all artists. The core principle of Kamoinge was the importance of black photographers documenting black life, and pushing back against the limited racial views disseminated by white photographers.

“In the art of photography, I’m dealing with light, I’m dealing with all these elements, getting that precise moment. Getting the feeling, getting the way the light hits the person – to put it simply, these pieces are like the blues.” – Ming Smith

“Invisible Man” Series

Between 1988 and 1991, Smith produced her “Invisible Man” series. She borrowed the title of the series from the 1952 Ralph Ellison novel of the same name. The series is comprised of ethereal photographs in which black figures are captured between visibility and invisibility – turned away faces, hidden in the shadows, marginalised, hinting at the very real struggle African Americans faced to be seen and heard.

“August Wilson” Series

In the early 1990s, Smith worked on her “August Wilson” series, a fascinating project in which she retraced the footsteps of the playwright August Wilson in the Hill District of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where he grew up and on where he based most of his plays. Smith wandered around, photographing the people and places that she imagined could have featured in his plays. August Wilson made marginal people monumental, which is why Smith loved his work so much and which is what her “August Wilson” series also strove to do in its own way. Penetrating portraits and heartwarming everyday scenes of people she encountered during her explorations of the neighbourhood are the result of her series.

© Ming Smith, Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery

MoMA Acquisition and More Widespread Recognition

In 1975, Smith dropped off a portfolio of her photographs for review at the Museum of Modern Art, although the receptionist assumed she was a messenger. When she returned to pick up her portfolio, she was ushered into the curators’ offices and told that the museum was very interested in acquiring some of her works. However, Smith was not happy about the price that was suggested, which wouldn’t even have paid for her expenses. Not one to acquiesce so easily, Smith told the curator straight up that this wouldn’t do, and the curator urged her to reconsider. Smith eventually accepted, thus becoming the first female African American photographer to have her prints acquired by the MoMA’s permanent collection.

Despite this MoMA milestone, which came relatively early in her career, Smith received little attention from the established art world for the next 40 years. Though she did have some exhibitions, they were relatively few and far between. Smith explains that though she was around, nobody really sought her out. It’s really only the past 10 years that Smith has slowly started gaining more and more well-deserved widespread attention and recognition for her unique body of work. The 2010 MoMA show “Pictures by Women: A History of Modern Photography,” was a big turning point for Smith.

© Ming Smith, Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery

Representation and Recent Exhibitions

Smith is now represented by Jenkins Johnson Gallery and Steven Kasher Gallery. She was included in the touring exhibition “Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power” (2018-2019) organised by Tate Modern in collaboration with the Brooklyn Museum, Crystal Bridges and The Broad, and in the Brooklyn Museum’s “We Wanted A Revolution: Black Radical Women, 1965-85” (2017). In 2017, she collaborated with video artist Arthur Jafa on his exhibition at the Serpentine Gallery in London. In 2019, she had her first solo show in London, showing vintage black-and-white prints from her “August Wilson” and “Invisible Man” series at Frieze Masters.

Her photographs are held in the collections of MoMA, the Whitney Museum of Art, Philadelphia Museum of Art, Detroit Institute of Arts, Virginia Museum of Fine Art, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Smith’s work, which she always believed to be bigger than herself, is finally starting to gain the prominent place it deserves.

© Ming Smith, Courtesy Steven Kasher Gallery