Articles and Features

Coronavirus Street Art: How The Pandemic Is Changing Our Cities

“There can be no return to normal because normal was the problem in the first place.”

Graffiti in Hong Kong

Whilst the coronavirus pandemic has plagued our world in recent months, forcing almost the entire world to enter lockdown and people to stay home, the creative response to the crisis has been extraordinary from several perspectives.

Many artists living in self-isolation or under strict lockdown measures turned inwards for inspiration and numerous hitherto unexplored paths, largely due to the inescapable state of introspection and the absence of physical human connection. Ordinary laymen have rediscovered art in unexpected ways, among the oddest being the Getty Museum’s initiative to recreate iconic artworks through tableaux vivant. The project has gone viral and thousands of gems can be found under the hashtags #Gettychallenge and #betweenartandquarantine on Instagram.

However, while most people were at home – artists or not – street artists have found their way to bring urgent messages of hope, resilience, and dissent – sometimes with a dose of sardonic humour – performing as solitary actors in cities which unwittingly resembled the emptiness of Edward Hopper‘s paintings. Now that the situation is slowly returning to normal in many countries, we will soon discover that the pandemic, as well as many other aspects of our lives, has also affected the appearance of our urban environments.

One of the most popular themes of the recent Coronavirus-inspired street art has been the support and gratitude to all key workers who have been facing great personal risk on the front lines, particularly healthcare workers and medical professionals.

The most prominent of these pieces is probably Super Nurse! that the street artist known as FAKE has painted in Amsterdam. As an “ode” to all healthcare professionals around the world, it shows a nurse wearing a face mask emblazoned with the Superman logo. The work was also projected in London as part of one of the world’s biggest permanent digital public art installations (organised by W1curates) as well as on the side of NYU Langone hospital in NYC Manhattan for several nights.

Surprisingly, while street artists were venturing out into quiet streets, the king of graffiti, the elusive Banksy, had turned on this occasion to canvas to realise Game Changer, a picture depicting a kid playing with a nurse superhero toy, while Batman and Spiderman action figure toys lie discarded in a nearby wastepaper basket.

The framed work has been unveiled at the Southampton General Hospital in southern England along with a note by the artist for hospital workers, saying: “Thanks for all you’re doing. I hope this brightens the place up a bit, even if only black and white.” According to a spokesperson for Banksy, the artwork will head to auction to raise funds for the National Health Service at a later date.

However, numerous spray-paintings, stencils, and posters have sprouted up to spread messages of encouragement and hope to ordinary people.

In Los Angeles, where an incredible quantity of graffiti has popped up, a sunshine-yellow mural brightens the Doheny Wall in West Hollywood as part of the Hope Dealer series by local artist Corie Mattie. The picture shows a person wearing a mask and a white coat, opening one side of it to reveal the word “HOPE” scrawled in the inner pockets. The text reads: “Cancel Plans. Not Humanity.” The artist has also been making signs across the city that say “If you’re reading this, go home.”

In addition to reassurance and support, there have been exhortations to adopt safe behaviours, first and foremost staying at home, but also washing one’s hands and respecting social distancing as the only way to protect oneself and others.

Certainly, also meta-art references are abundant: an army of Mona Lisas with face masks has invaded the streets and even Banksy’s iconic Girl with a Pierced Eardrum in Bristol has been given a mask to face the health crisis.

Among many other examples of art historic in-joking to stand out include the “sterilised” reinterpretation of the 1859 painting The Kiss by Francesco Hayez, realised in Milan by Italian urban artist Salvatore Benintende, known as Tvboy, where the lovers have been provided with face masks and hand sanitizers.

Meanwhile, miles away on the streets of Ladywell, south-east London, an updated version of the iconic Caravaggio work Dinner at Emmaus has appeared, placed there by the hand of street artist Lionel Stanhope. The original 1601 painting depicts a resurrected Jesus appearing to two of his disciples at a table spread with a meal but in Stanhope’s spray-painted version, Jesus is wearing surgical gloves. Lockdown has given the artist the time and space removed from eager law enforcement to reproduce on a large-scale the artwork he has always admired.

But what would street art be without its usual ability to sharply express dissent?

If issues like privatization, surveillance, increasing marginalization, housing were already addressed by artists in the public space, all the more so in recent circumstances, street art has become part of the debate around contemporary politics. Powerful accusations against politicians have appeared on the walls of cities across the globe, along with more general criticism of today’s societal contradictions. A graffiti popped up in Hong Kong clearly states “There can be no return to normal because normal was the problem in the first place”.

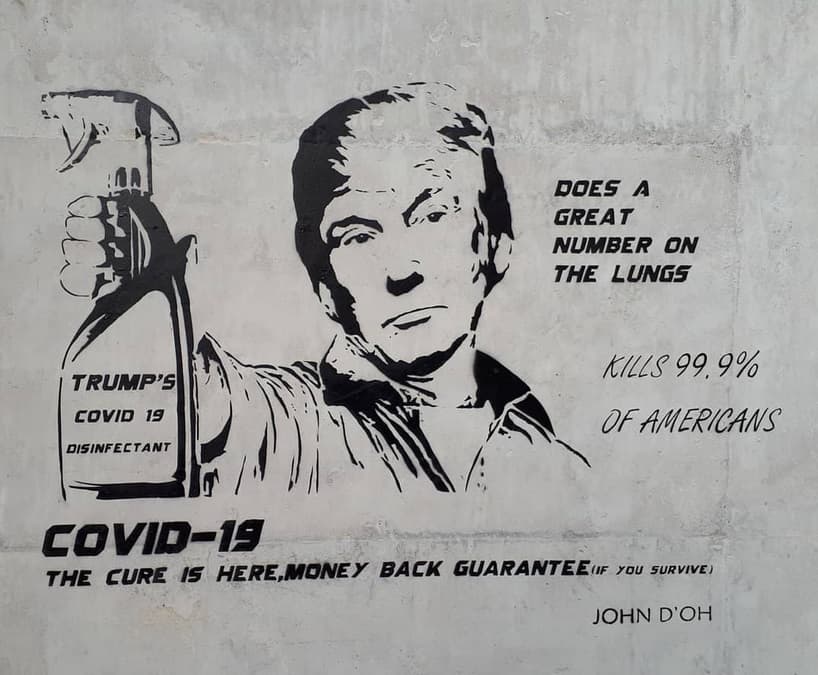

Of all the politicians targeted, of course US President Trump stands out, especially after his controversial statement about injecting disinfectant as a potential solution to Coronavirus infection.

Not to mention Chinese president Xi Jinping. The Australian artist Lushsux shows him wearing a hazmat suit while saying, “Nothing to see, carry on” alluding to the apparent lack of transparency in reporting pandemic-related data by the Chinese authorities.

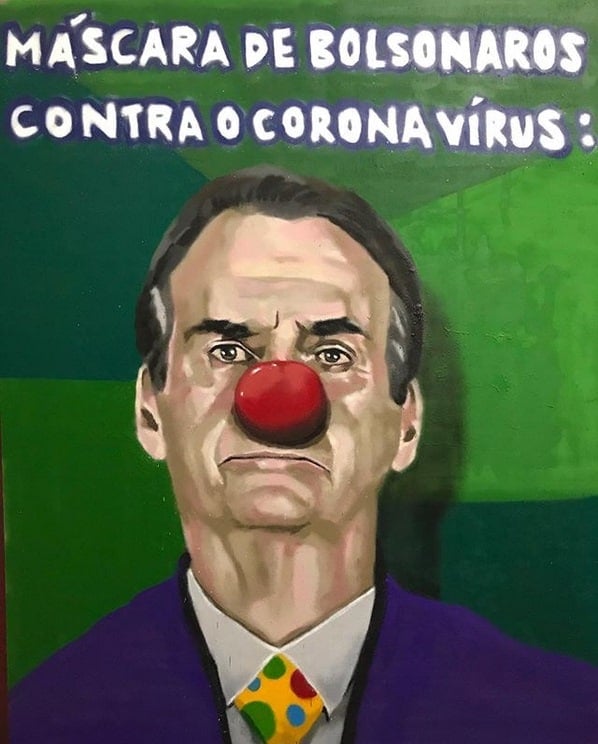

Other divisive figures have also failed to escape graffiti-based scrutiny. Jair Bolsonaro, right wing president of Brazil, who has discouraged social distancing and lockdown, when asked about the country’s rapid increase in Covid-19 cases replied “So what? What do you want me to do?” has been represented wearing a clown nose by Brazilian street artist Aira Ocrespo, in addition to the wording “Bolsonaro’s mask against Coronavirus”.

Street artists have proven to be the perfect mouthpieces for entire communities, adding levity and incisive commentary on other aspects of the pandemic, at times playfully, at times cynically. They especially lampoon the panic buying and the ridiculous toilet paper hoarding that afflicted many communities in the early days of lockdown. In Berlin, there’s a mural by Dominican street artist Jesus Cruz Artiles, aka EME Freethinker, depicting the character Gollum from Lord of the Rings worshipping a roll of toilet paper and uttering his famous line “my precious!”. While in Los Angeles a shady figure suspiciously opens his smuggler’s trenchcoat revealing a toilet paper supply.

Tensions and social changes inevitably have an impact on art – a recent Time article has shown how the 1918 flu pandemic was an inescapable part of the zeitgeist of the time and how much it influenced the art movements that followed.

Even though it is now difficult to predict how the Coronavirus crisis will affect art in the immediate and further future, the powerful immediacy of street art has once again demonstrated its ability to capture the general mood as well as to express the manifold contradictions of our time.

Relevant sources to learn more

You and Me and Everyone We Know: How the Coronavirus Is Affecting Art, Life, Work and Everything Else

The Rallying Cry of Street Art During Coronavirus | Mashable

10 Poignant Works of Street Art Around The World in Support of Ukraine