Articles and Features

Philip Guston, When?

By Adam Hencz

What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?” — Philip Guston

Cartoonish blood-spattered hooded figures cruising down the road, smoking cigars and plotting. Similar characters standing in a cell-like room surrounded by empty flasks. Another one painting a self-portrait in his studio. The anxiety about the viewers’ response and the fear that Guston’s repeating motif of Ku Klux Klan members might be misinterpreted has compelled four institutions to step back and postpone the long-planned traveling retrospective of the artist until 2024. The exhibition, Philip Guston Now, was set to open this year and visit the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and the Tate in London. The cancellation caused backlash from the artistic community, leading to the publication of an open letter published on Wednesday, signed by more than 100 artists, critics and curators stating that “these institutions thus publicly acknowledge their longstanding failure to have educated, integrated, and prepared themselves to meet the challenge of the renewed pressure for racial justice”. Will these issues be blown away in four years? If not now, when would be the appropriate time to face the potential for evil in all of us and to reflect on the injustices deeply embedded in our society?

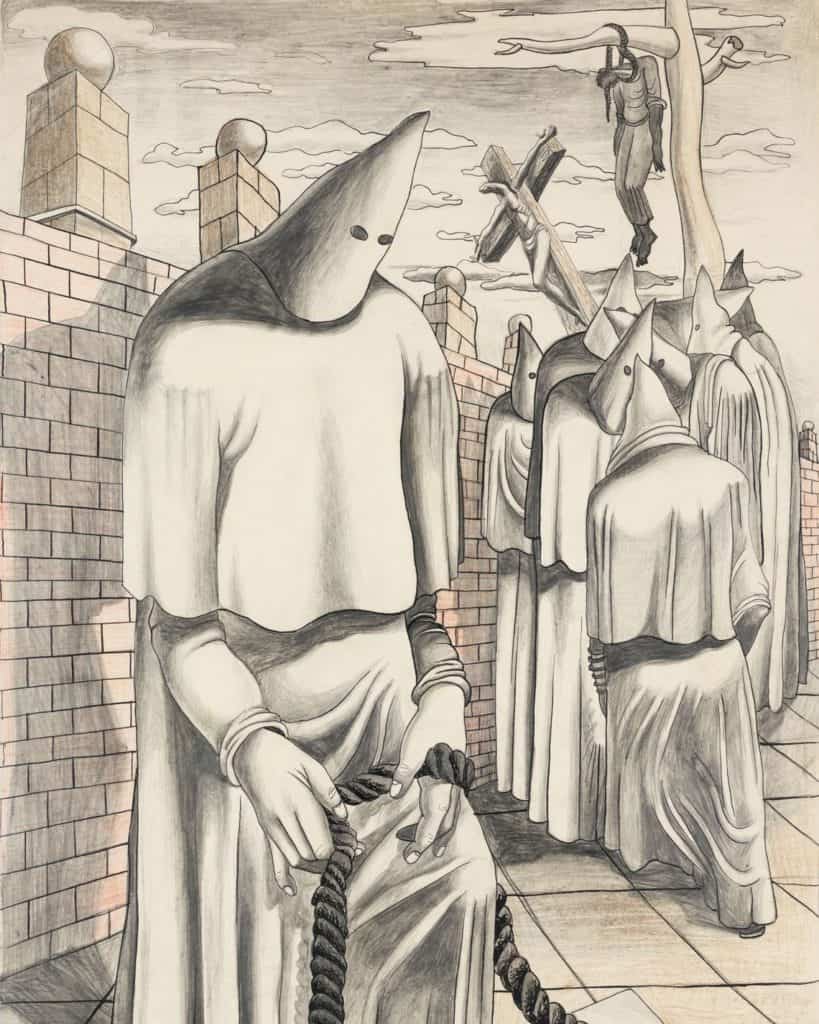

Growing up in LA, Guston witnessed the racist terror of the Klan, and from an early age, he was involved in left-wing politics that sought to address these socio-political issues. Guston’s daughter, Musa Mayer, reported in the New York Times: “My father dared to unveil white culpability, our shared role in allowing the racist terror that he had witnessed since boyhood. […] As poor Jewish immigrants, his family fled extermination in the Ukraine. He understood what hatred was. It was the subject of his earliest work.” The hooded figures first appeared in a boldly depicted scene completed in 1930, when Guston was only 17 years old. Dramatic modeling and the looming presence of the central figure convey the theme of oppression, as does the symbolic rope that hangs over blocks representing Louisiana and Mississippi. Guston’s visual analogy between the victim of a lynching and the crucified Christ can be seen at the back of the composition. The drawing served as the basis for his painting Conspirators, 1932. The hooded figure in the foreground, alternately absurd and sinister, recurs throughout Guston’s work.

Philip Guston, Then. The Early Years.

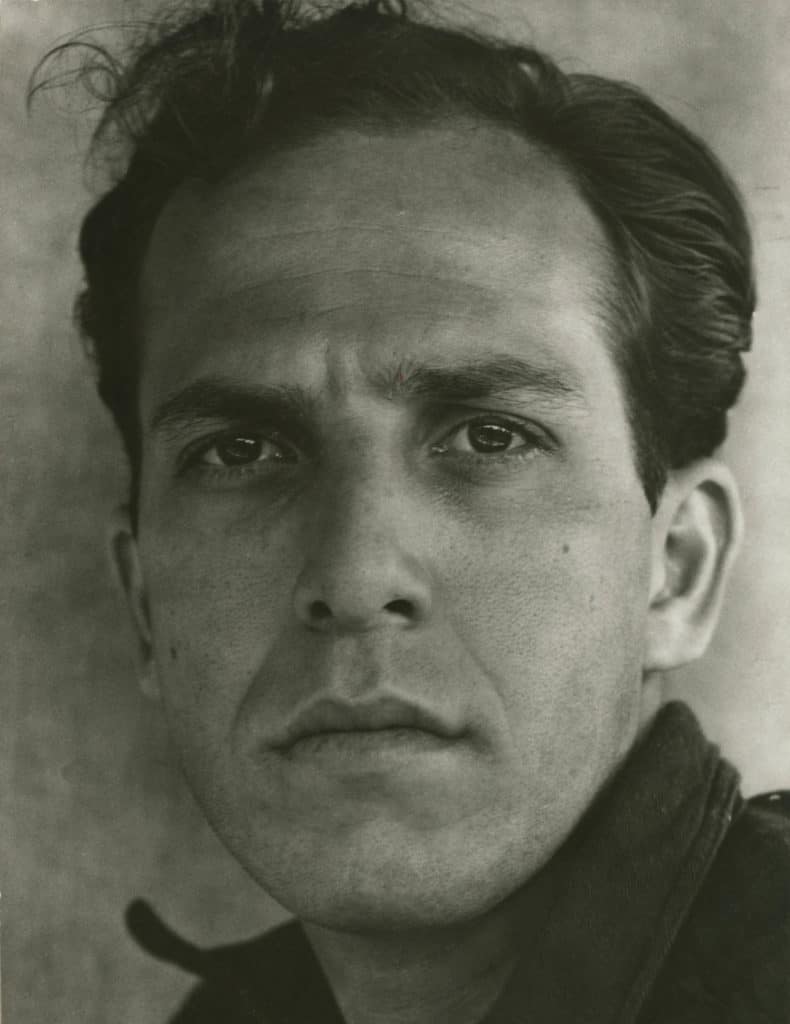

Born in 1913, in Montreal, as Phillip Goldstein, Guston was born the youngest of seven children of Russian-Jewish parents, who had fled persecution in the early 1900s. In 1922, seeking better economic conditions, the Goldstein family moved to Los Angeles, where Guston enrolled in the Manual Arts High School and met classmate Jackson Pollock. The two got expelled for distributing satirical leaflets, Pollock was readmitted, but not Guston, who never returned to formal art education and continued to study and paint independently. Guston was awarded a scholarship to study at the Otis Art Institute in 1930. He entered with enthusiasm but soon got disappointed by the traditional methods taught there, and he left after three months.

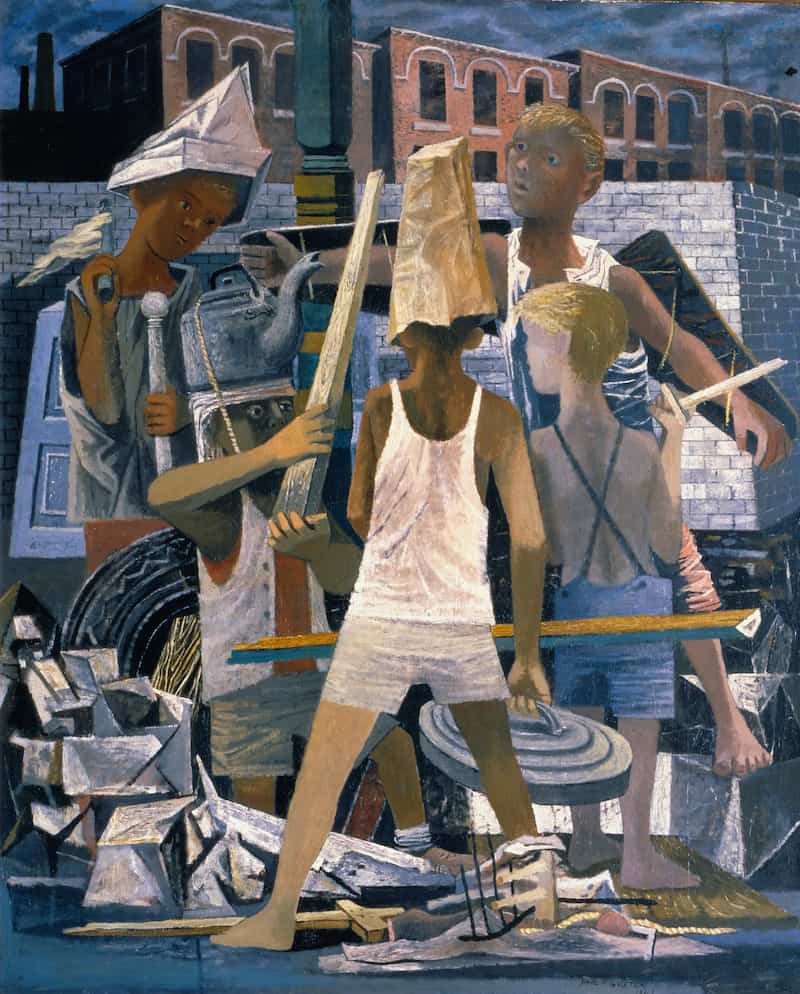

The year 1930 also marked the completion of his first major work, Mother and Child. In his early years as an artist, he was greatly influenced by French surrealism and the ideas of prominent Mexican muralists promoting social change. During the 1930s he painted monumental frescos and political murals across America and Mexico. In 1936 Jackson Pollock convinced Guston to move to New York where he met fellow painters Arshile Gorky, Willem de Kooning and Mark Rothko who were all finding their ways into the prevailing modes of abstraction in the ‘30s. However, Guston kept on experimenting with figures, grounds, solid spaces and objects until the 1950s.

Abstraction.

In the early 1950s, when abstract expressionism was already at its zenith, Guston himself began experimenting with abstraction. His earliest pieces in this mode featured clusters of various colors situated at the center of canvases, resembling the approaches of already established artists. Guston often positioned those vibrant groupings of shapes and lines against subdued backgrounds of pinks and blues, colors that would persist in later works.

Late Work And Back To Figuration.

“There are times in one’s life,” Guston wrote in a letter to his friend. “When you begin all over again, from the beginning. A true turning over.” By the late 1960s Guston had abandoned abstraction, harboring feelings of wanting to change. The political climate of the US in the ’60s also impacted the artist’s shift away from complete abstraction, as he felt that it was a subject that his work could no longer ignore. He once said, “The war, what was happening to America, the brutality of the world. What kind of man am I, sitting at home, reading magazines, going into frustrated fury about everything—and then going into my studio to adjust a red to a blue?”.

After a painful separation from painter and poet Musa McKim, his wife for nearly 30 years, Guston found himself in despair. He eventually moved to his Woodstock studio and once again drawing became both his inspiration and refuge. He developed prototypes of elements and figures which became imperative to the rich symbolism in his late works, returning to representation in a mannered style replete with a scathing satire. By the end of 1969, Guston had filled his big new studio with dozens of paintings of the hooded figures in various scenarios. Of these figures, Guston said, “They are self-portraits. I perceive myself as being behind the hood. . . . The idea of evil fascinated me . . . I almost tried to imagine that I was living with the Klan. What would it be like to be evil?”.

Breaking away from the abstraction for which he had become renowned came with a price. His new works received little appreciation from the public and the critical response of his October 1970 show at Marlborough Gallery was resoundingly negative, sparking outrage of fellow painters by Guston’s betrayal. Immediately after the opening, Guston escaped to Italy for almost a year, for a residency at the American Academy in Rome, where he continued to develop his newly adopted artistic language. Over the course of the 1970s Guston left the hooded figures behind for more direct and at times confessional imagery and developed a distinct figurative vocabulary and palette. After leaving Marlborough Gallery, David McKee opened a gallery of his own with his wife, Renee Conforte, and in 1974 held the first of seven solo Philip Guston exhibitions at the gallery over the six years that followed. Towards the end of the ‘70s, Guston’s works began to sell and slowly found their ways into museum collections.

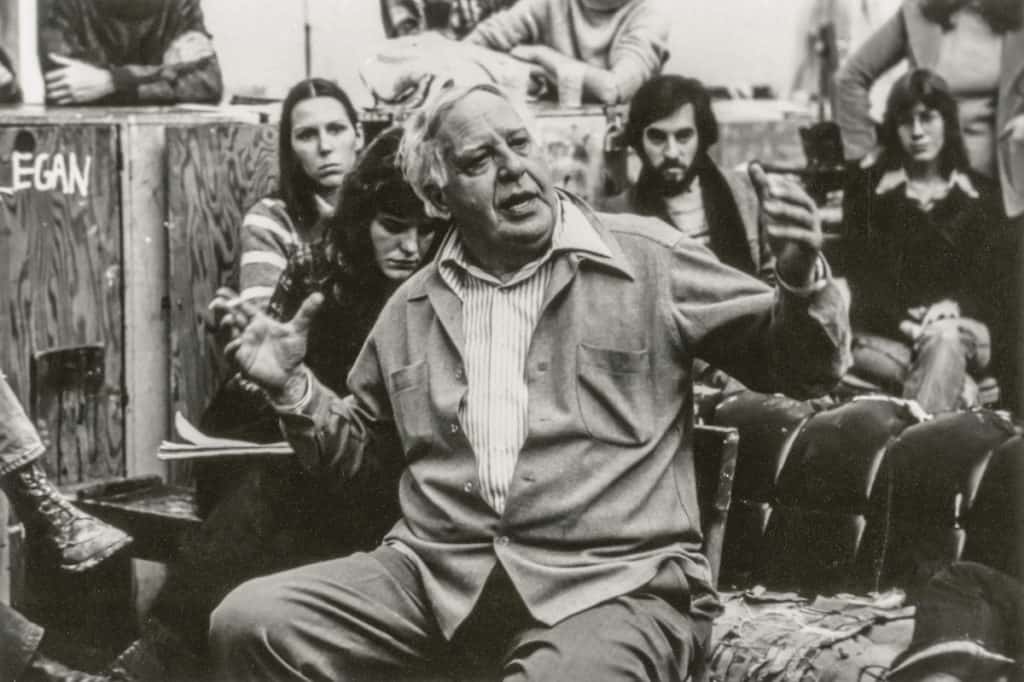

Henry Hopkins, director of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, invited Guston to exhibit a major retrospective in the spring of 1980, and had agreed to place an emphasis on the late work. “It’s not so much a painting show. It’s a life. A life lived.” Guston told a small circle of journalists at the opening of the retrospective. The decades of smoking and drinking had taken their toll and despite his declining health and previous heart attack, fearful of hospitalization Guston refused medical attention and kept himself alive to witness his “life lived” on the walls of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. A few weeks after the celebrations, while dining at the home of Woodstock friends, Philip Guston suffered a second, fatal heart attack.

“The danger is not in looking at Philip Guston’s work, but in looking away.” — Musa Mayer

Guston frequently created work about racism, antisemitism and fascism and shared his inspirations, creative process and practices while teaching at numerous universities and art institutions during his lifetime. He was an advocate of self-reflection and emphasized the power of art in promoting social change. After all, in The Studio, when depicting himself hooded and busy at the easel, complicit in racist violence, but with a strong will to overcome it, he created the ultimate metaphor for today’s leitmotif of white privilege, that insidious and pervasive upholder of advantage that is somehow only being properly acknowledged now in a widespread way. The upcoming retrospective could have accelerated the transformation of museums and their consciousness into institutions that can work for all artists and represent relevant issues and the experiences of all publics. As the artist’s daughter Musa Mayer released in his statement: “This should be a time of reckoning, of dialogue. These paintings meet the moment we are in today. The danger is not in looking at Philip Guston’s work, but in looking away.”

Mark Godfrey, Senior Curator of International Art at Tate Modern, who had been working on the show, took to social media to further express his own consternation with the decision. He reiterated Mayer’s comments about Guston’s anti-racist position and writing, and as as part of a lengthy statement of his own went on to say that: “Cancelling or delaying the exhibition is probably motivated by the wish to be sensitive to the imagined reactions of particular viewers, and the fear of protest. However, it is actually extremely patronizing to viewers, who are assumed not to be able to appreciate the nuance and politics of Guston’s works.” The implications are clear–the reasons for the postponement (tantamount to a cancellation in his view) have little to do with Guston’s work itself and much more to do with the institutions’ lack of faith in their curators and lack of belief in the intellect of the general public’s ability to navigate the subtleties of Guston’s oeuvre.

Relevant sources to learn more

Philip Guston Now – Statement from the Directors

Open Letter On: Philip Guston Now

Philip Guston Foundation: A Chronology

Art Movement: Abstract Expressionism