Articles and Features

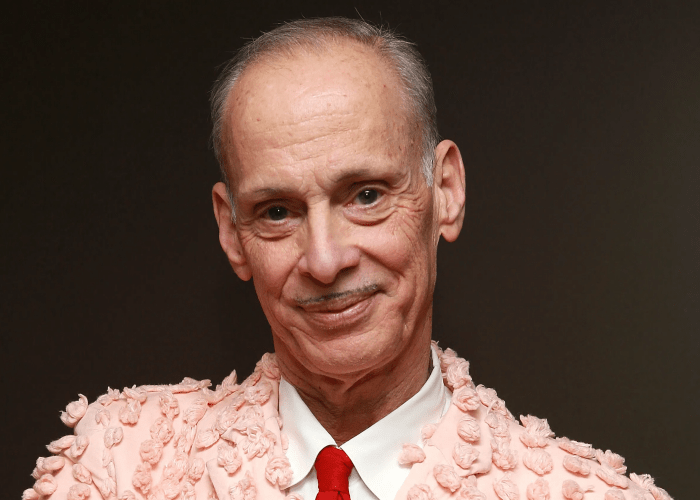

The Other John Waters: The Pope of Trash And His Visual Art

By Shira Wolfe

“To understand bad taste one must have very good taste. Good bad taste can be creatively nauseating but must, at the same time, appeal to the especially twisted sense of humor, which is anything but universal.” – John Waters

This article series explores the lesser-known creative output of artists who became famous for another medium or genre of art. Often, great artists wear many different hats, but break through and achieve acclaim because of their work in one specific medium. To highlight the multifaceted nature of their talent, we seek to uncover the lesser-known side of their artistic production. This week, we reveal how cult film director John Waters’s outrageous vision extends into his visual art.

The Films of John Waters

Baltimore-born cult legend John Waters made quite a name for himself in 1972 when his film Pink Flamingos premiered at the Baltimore Film Festival. Not long after, it was picked up and screened as a midnight movie at the legendary Elgin Theater in Manhattan, succeeding the very first midnight movie, Alejandro Jodorowsky’s surreal tour-de-force El Topo. Waters called Pink Flamingos “a terrorist act against the tyranny of good taste.” Starring his long-time muse, drag queen Divine, Pink Flamingos is an outrageous film filled with bizarre social misfits competing with each other for the title of filthiest person alive. Fittingly, the movie ends with a scene in which Divine picks up real dog shit off the sidewalk and eats it. Pink Flamingos is the first in a series of what Waters dubbed his “Trash Trilogy”, also including Female Trouble (1974) and Desperate Living (1977) – all films that pushed the boundaries of outrageous filmmaking and pure bad taste. Waters’ real commercial breakthrough came with Hairspray (1988), which became a huge success and was adapted into a Tony Award-winning musical. In 1990 he released Cry Baby, another mainstream success starring Johnny Depp. Waters would later say about Hairspray that it was one of his most devious works of art. After all, he managed to sneak messages into mainstream, conventional society that encouraged beauty standards that differed a great deal from received societal norms. The film also encouraged teenagers and young adults to be comfortable being themselves, also making light of interracial relationships, an extreme rarity in mainstream cinema and television of the time. Waters’ gritty, colourful and and camp aesthetic is unmistakable in all his films, and doesn’t end there. He also enjoys forays into the visual arts, creating works that embody the same characteristic aesthetic of high and low culture seamlessly intertwined together.

“What I’m trying to do is investigate the undersides of both the art world and the movie business – both of which I love.” – John Waters

The Visual Art of John Waters

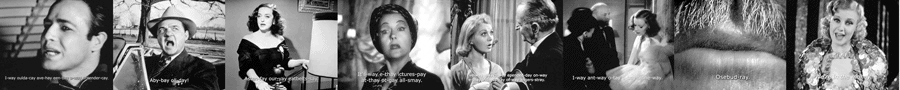

Waters started creating photography-based work and installations in the early 1990s. He explains that it all began when he needed a still from one of his movies. He put the VHS tape in his TV set and took a photograph of the television screen. This resulted in an image that looked similar to the movie, was derived from the movie and yet had a quality of its own. Waters continued this practice with other films, lining up shots that captured telling moments and interesting details from the filmic narrative, to create a new sequence of the film’s arc in a mock storyboard format. In this way, Waters would in essence “redirect” his favourite films, playing with the act of appropriation through the lens of his sharp directorial eye.

Waters’s visual art is very much concerned with the same issues he explores in his films. He explains: “What I’m trying to do is investigate the undersides of both the art world and the movie business – both of which I love.” Through his renegade humour, he reveals the deep-seated ironies in the world. He also explores the thin line between art that is funny yet retains its essential communicativeness,, and art that is too funny, where an inherent message risks being subsumed by comedy.

In one series, Waters shows photographs of celebrities including Justin Bieber, himself, and Lassie the dog-star, with facelifts. “I only make fun of things I really like,” he states. At other times, Waters tackles darker moments in history, always approaching them with a certain dose of humour. For example, there is the photograph of JFK and Jackie Kennedy disembarking an aeroplane, followed by the Grim Reaper from Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal. In another work, Waters shows two film titles of the movies that were scheduled for screening on the doomed flights of 9/11. Waters loves a good taboo – which explains why he made a piece in which he photoshopped cigarettes in the mouths of Hollywood child stars (Children Who Smoke, 2009).

Waters often collaborates with other people when he’s making his installations and sculptural works, and compares the process to making a movie. Typically he ideates and settles on a composition and medium, with the resultant artwork having been fabricated by an (often credited) collaborator. This is the case, for example, with his Have Sex in a Voting Booth buttons from 2004, and his Playdate (2006), a bizarre, hilarious and ultimately disturbing sculptural piece that depicts Michael Jackson and Charles Manson as toddler hybrid mannequins playing together. For this piece, Waters worked with Tony Gardner, who made Chucky in the Child’s Play movies.

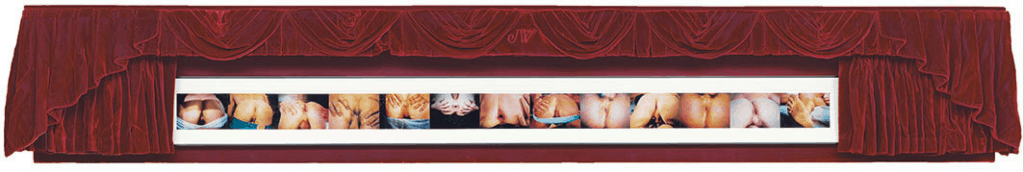

Indecent Exposure

In 2018-2019, the Baltimore Museum of Art hosted the first retrospective of Waters’s visual art in his hometown. Showing over 160 provocative photographs, sculptures, video and sound works, the show covered the breadth and depth of Waters’s vast creative output. His “redirected” film storyboards, film stills of Divine and facelift photos were followed by sculptural works, films (including Kiddie Flamingos from 2014, Waters’s less X-rated version of Pink Flamingos featuring schoolchildren doing a reading of his script) and finally, ending the exhibition, three peep show booths. Each of the booths were equipped with a chair and a box of Kleenex, and screens featured Waters’s rarely seen earliest films, which he made as a teenager in the 1960s. A notable highlight was the piece Twelve Assholes and a Dirty Foot (1996), showing still images of assholes next to a picture of a dirty foot. Waters scoured pornographic films to find these images – apparently it’s not easy to find what he calls the “lone-asshole” moment in the shot, and it’s allegedly even harder to find a dirty foot in porn, but somehow he managed, and spliced these rarities together in this resultant piece.

Mr. Know-It-All

For Waters, his practice can be distilled into the essentials of saving, editing and telling stories. No surprise, then, that he recently published a book entitled Mr. Know-It-All: The Tarnished Wisdom of a Filth Elder (2019), in which he gives his opinion on just about everything. Filled with eccentric and brilliant nuggets of Waters wisdom, it is an invaluable addition to the body of work of the Pope of Trash, also sometimes known as the Baron of Bad Taste. Mr. Know-It-All supports everyone in their creative struggles: “You need two people to think your work is good – yourself and somebody else (not your mother). Once you have a following, no matter how limited, your career can be born, and if you make enough noise, those doors will begin to open, and then, and only then, can you soar to lunatic superiority. Mr. Know-It-All is here to tell you exactly how to live your life from that day forward.”

Relevant sources to learn more

Read more articles in our article series about the lesser-known creative output of some of the world’s most beloved artists: