Articles & Features

The Shows That Made Contemporary Art History: Nazi Censorship And The ‘Degenerate Art’ Exhibition of 1937

There are multiple ways to delve into the fascinating world of contemporary art. One may consider the development and succession of different artistic movements; the personalities of the major players in the field; not to mention the most iconic artworks that have defined our era. But why not consider the history of art exhibitions themselves? Landmark shows of the modern and contemporary periods have impacted and shaped the course of art history, both launching entirely new genres and shaping the history and habits of exhibition-making through innovative practices. This week we explore the Degenerate Art exhibition, opened in Munich in 1937, one of the most shameful chapters of art history and, simultaneously, one of the most surprising. Conceived by the Nazi regime to condemn modern art by showing its alleged perverse nature, it ironically became not only the ultimate backhanded compliment to the participants but the most popular art show of all time.

The background

In the first decades of the 20th century, Germany was one of the major hubs of modern art in Europe. Following the early radical experience of Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter, under the Weimar government of the 1920s, the country saw a further renaissance that affected the cultural scenery in all its aspects. A new approach to design flourished at Bauhaus, jazz bands and cabaret became popular, and Expressionism extended from painting and sculpture to architecture, literature, theatre, dance, and cinema with masterpieces such as The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari by Robert Wiene (1920) and Nosferatu by Murnau (1922). However, this cultural golden age did not last long. The socio-economic instability resulting from the onset of the Great Depression in the United States laid the groundwork for the Nazi party to nurture and meet a growing consensus. When Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor in January 1933, drastic change was visited upon all aspects of German society.

The Nazi government considered the Weimar mores – mostly of American influence – as obscene and antithetical to traditional German values, making the Weimar culture, along with avant-gardism art in all its aspects, a threat in terms of both formal and intellectual expression. In September 1933, Joseph Goebbels, the Reich Minister for Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, was put in charge of the Reich Culture Chamber, whose members – all ‘racially pure’ Party supporters – were the only ones “allowed to be productive in our cultural life”.

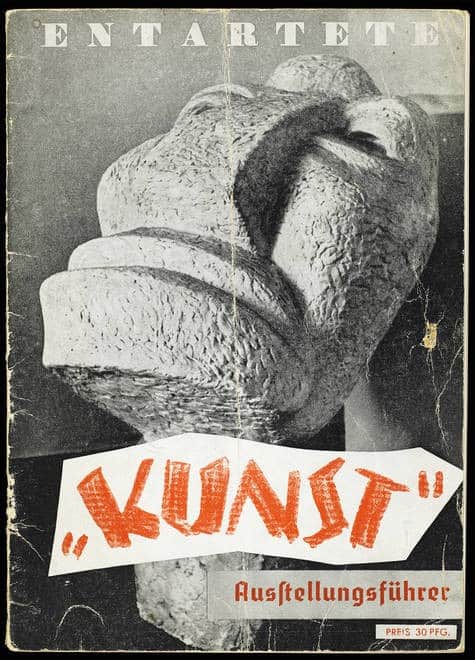

The assault on modernism was manifested in numerous systematic cleansing actions. Artists and musicians were discharged from teaching positions; museum directors that displayed modern art were dismissed; books were burnt; music, films and plays censored; thousands of artworks confiscated from public collections. The majority were destroyed, while others, those considered ‘marketable’, sold abroad to raise funds for the regime. This extensive purge targeted what the Nazis deemed Entartete Kunst – ‘degenerate art’.

Degenerate Art

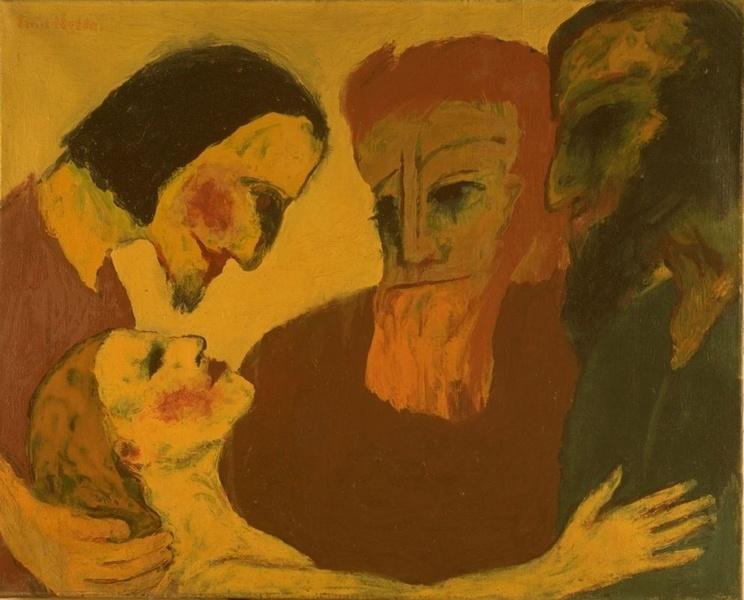

With the term ‘degenerate art’, the Nazis labelled all art forms that, in their view, stood in opposition or obstacle to the purification of German culture. Inevitably associated with liberal democracy, they perceived modernism as a sign of cultural decline as well as a deliberate attack against German people. Entartete were those works that “insult German feeling, or destroy or confuse natural form or simply reveal an absence of adequate manual and artistic skill”.

It was not simply a matter of style, although a literal social realist figuration was the preferred idiom. What did not comply with the stereotypic representation of beauty and did not convey the values of militarism, racial purity, and heroism was forbidden, resulting in the banning of subjective, unconventional, and non-figurative art; basically everything that was irrational or remotely interpretable – from the Cubists’ fragmentation of reality to Fauves’ unrealistic colours and the pioneering examples of abstract art.

Along with aesthetics, the determination of what was degenerate or not was also an indispensable propaganda tool. Since the National Socialists aspired to war, the depiction of the horrors of war by artists of the Weimar Republic that had suffered the brutality of World War I, like Otto Dix, and Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, were unacceptable. War scenes could only suggest courage, masculinity, and heroism.

The concept of degeneracy, taken to the extreme during the Nazi regime, was actually well-rooted in German sociology. The first to introduce the term in 1892 was the German physician Max Nordau in his book titled, in fact, Entartung (‘Degeneracy’). Inspired by the criminologist Cesare Lombroso who attempted to prove that specific physical characteristics were indicative of criminal tendency, Nordau developed the idea that modern art was the product of perverse souls living in a corrupted society. This distorted idea was widely debated and culminated with the publication of Art and Race by Nazi architect Paul Schultz-Naumburg in 1928. According to his disturbing theory, modern ‘degenerate’ art reflected mental or physical disabilities, supposedly manifestations of ‘racial deficiencies’. Therefore, those who promoted it were secretly trying to undermine German ‘racial purity’, namely Jews and Bolsheviks.

Degeneracy was, however, a fluid notion and its definitions were not always so clear, if not even contradictory. For example, Felix Nussbaum, German-Jewish surrealist painter and victim of the Holocaust, was not in the blacklist, while the work of Emil Nolde, anti-Semite, and determined Nazi supporter, was deemed degenerate with over one thousands works confiscated from German institutions. Ultimately, the final arbiter and judge was Hitler and his personal taste.

The show

Museums’ purging was not enough to satisfy the Nazis’ Bildersturm (‘iconoclasm’). With a cunning propaganda strategy, they realised that the best way to discredit modernism and inflame the public opinion against it was not to hide it from public view but display it in the spotlight instead. Thus, at the suggestion of Joseph Goebbels, Hitler signed an order authorizing a Degenerate Art Exhibition. A parallel show, the Great German Art Exhibition, was already planned to take place simultaneously to celebrate the regime values in a conventional academic style. Other so-called ‘shame exhibitions’ had come first, but the one mounted in Munich in 1937 would become the biggest.

Adolf Ziegler, head of the Reich Chamber of Visual Art, as well as Hitler’s favourite painter, was in charge of a commission that toured Germany for two weeks in search of works according to criteria of ‘decadence’, ‘weakness of character’, ‘mental disease’, and ‘racial impurity’. They confiscated over 5000 pieces, of which around 600 were included in the Degenerate Art exhibition. On 19 July 1937, the show opened its door after Ziegler’s incendiary speech: “German ‘Volk’, come and judge for yourselves!”

The selected venue was the Institute of Archaeology by reason of its dark rooms and narrow corridors, in open contrast with the monumental Haus der Deutsche Kunst that Hitler had purpose-built for the Great German Art show, launched the day before.

The exhibition featured paintings, sculptures, prints, and books authored by many great international names of modern art, mainly German but exclusively so. From Nolde, Heckel, and Kirchner to Matisse, Picasso, and Van Gogh but also Klee, Archipenko, Chagall, Kandinsky. All forms of modernism were covered – from Impressionism to New Objectivity – and juxtaposed, with complete disdain, with works by patients of mental institutions.

In the first three rooms, artworks were categorised thematically; blasphemous pieces, art by Jewish or Communist artists, art offensive to the German people. The rest had no specific theme.

Insulting and derisive slogans ran across the walls; texts like “Nature, as seen by sick minds”, “madness becomes method” or “revelation of the Jewish racial soul”.

Intentionally, the organisation was curatorial chaos. Works were amassed incoherently in overcrowded spaces. They were often unframed, incorrectly attributed, and labelled; also accompanied by quotations from artists reported wrong or out of context.

Today, apart from a few photographs, there remains silent footage shot by American cinematographer Julien Bryan, who later stated: “People might not believe my story if I told it in words when I returned to America. Everyone would believe my pictures”.

The legacy of the ‘Degenerate Art’ show

The exhibition lasted four months and then went on to tour the country. In Munich alone, it attracted more than two million visitors, an average of 20,000 people per day, making it the most popular modern art show of all time.

Though realised with the deliberate intention of triggering negative reactions, lines for the show went around the block. Indubitably, many were drawn by the air of scandal surrounding the event; others went in hatred stoked by the regime in order to disregard modern art; but many attended in the realisation that it could be their last chance to see such masterpieces. Unintentionally, Hitler did more to promote modernism than anyone before him. But the greater irony is that the Degenerate Art exhibition hugely outnumbered the Great German Art show attendances, receiving almost four times the number of visitors.

On the occasion of the first anniversary of the Degenerate Art exhibition, a group of collectors and dealers in London set up a show entitledTwentieth-Century German Art, essentially the art world of the day’s international response to Nazi censorship.

In 2014, the Neue Galerie in New York hosted Degenerate Art: The Attack on Modern Art in Nazi Germany, consisting of a number of paintings and sculptures from the 1937 exhibition in contrast with Nazi-approved art from the Great German Art show. The works were also complemented by original documents of the event as well as empty frames symbolic of all those artworks tragically destroyed or lost. It was a poignant commemoration of one of the most reviled, and celebrated, exhibitions of all time.

Relevant sources to learn more

Explore the complete inventory of ‘Entartete Kunst’, the Nazis’ ‘degenerate art’ at Victoria & Albert Museum.

For previous editions of our “Shows That Made Contemporary Art History” series, see:

The Salon Des Refusés

The First Exhibition Of ‘Der Blaue Reiter’

The Armory Show